Imagine a bustling club in Los Angeles, nestled on the corner of Sunset Boulevard at 1451 Cahuenga Boulevard. The line stretches out the door, filled with vibrant young men and women, eagerly mingling with the hottest Hollywood stars and entertainers. There's no cover charge, no entrance fee — everyone who steps through the door is a V.I.P. Inside, the walls are adorned with vibrant Western-themed murals, a testament to the transformation of this once-abandoned nightclub and former livery stable. The air is filled with live music, the dance floor is a constant whirl, and the food and cigarettes are freely given. This was the Hollywood Canteen, a place of respite in the midst of World War II.

On December 7, 1941, America was at war, and Hollywood was ready for its close-up. Three days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the Hollywood Victory Committee was established with Clark Gable acting as its first chairman. It wouldn’t last long. After enlisting his wife Carole Lombard to help sell over $2 million on her tour of Indiana selling war bonds, she tragically died in a plane crash on her return flight to Los Angeles on January 16, 1942. In August, Gable enlisted as a private in the Army Airforce even though he was beyond draft age. He later entered Officers’ Candidate School in Florida and was assigned to the 351st Bomb Group. Although he wasn’t ordered or expected to do so, he flew operational missions over Europe in B-17s.

The Hollywood Victory Committee charged on. The Committee organized events between January 1942 and August 1945. After Gable, the chairmen included James Cagney, Sam Levene, and George Murphy. (Murphy also succeeded Cagney as president of the Screen Actors Guild and was later a prominent Republican politician serving as California’s Senator from 1965 to 1971.) Hattie McDaniel, the first black actress to win an Academy Award for her role in “Gone with the Wind,” was the Chairman of the Committee’s Negro Division.

Established for those in the film and entertainment industry not in active military service to help the war effort, its most notable success was the Hollywood Victory Caravan, which crossed the country with a stable of stars raising money by selling war bonds. For three weeks in April and May 1942, stars including Bob Hope, Cary Grant, Laurel and Hardy, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Barbara Stanwyck, Bing Crosby, and Desi Arnaz rode the rails, stopping in 14 cities and putting on over 300 performances.

Turn on those cameras, boys, we’ve got work to do! But it wasn’t just sound stages, city tours, and flashbulbs. Nope. In the throes of the fight for Western Civilization, there was one goal: victory. And that meant a full-fledged fighting force of young men (and some women) sent off to the far reaches of the earth, rifles in hand, to see and hear things they never imagined. America was off to war, mothers and lovers gave teary-eyed goodbyes to their boys, and those at home had their own call to action.

Factory work, material drives, Red Cross volunteers — civilians provided the material and service needed to support the millions of tons of armor, explosives, gear, and clerical duties needed to fight and win. But what about morale? Even with the Selective Service Draft, effective fighters and winners need the right motivation. And that’s where Hollywood found its greatest role. Our Boys had a final sendoff before they headed out into the great unknown to answer the call of duty, and on the Pacific Coast, that was the Hollywood Canteen.

Hollywood isn’t a place typically associated with modesty and altruism. So, why not lean into a little self-interested showmanship and pomp to gear up American fighting spirit for the cause of kicking Nazi and Imperial Japanese keister? Bette Davis and John Garfield are credited with the idea and launching it. Whether it was a sort of ploy to revamp her Queen Bitch reputation or make nice with Warner Bros. after a nasty lawsuit is unimportant. She put in the work, as the kids say.

In addition to serving as the Canteen president, Davis spent most nights at the club, tirelessly calling on her Hollywood colleagues to volunteer and arranging — with assistance and connections from the Hollywood Victory Committee — the startup and running of the Canteen. It was an enormous undertaking and required the cooperation of the major studios. Of course, the studio system helped with “volunteers.” Anyone under contract could be nudged (or, in military speak, “volun-told”) to put in a turn at the club. Warners had become the most vociferous anti-Nazi studio. Harry Warner, president of the studio, told the Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce in September of 1941, “You may correctly charge me with being anti-Nazi. But no one can charge me with being anti-American.” The four brothers — Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack — were second-generation Polish Jews, well aware of the Nazi threat even before America entered the war. As Lara Jacobson writes in “The Warner Brothers Prove Their Patriotism,” the studio was:

The first to cut ties with their German distributors, the first to produce a film showcasing to the world the injustices of the Nazis, and the first Jewish moguls in Hollywood. They were the first in many different scenarios, the studio was a consistent contributor to the war effort throughout the war and beyond. The Brothers did not just enlist their pictures, they enlisted their entire company to aid the Allies. This ranged from producing short training videos used by the military to donating actual pints of plasma to Red Cross who would pick it up from the studio.

By 1942, America was all in, and Hollywood was, too. The Canteen continued its run with Spencer Tracy carving Thanksgiving turkey and Marlene Dietrich serving hot dogs and sandwiches while Betty Grable, Hedy Lamar, Lana Turner, Shirley Temple, and Lauren Bacall took turns on the dance floor. Jo Stafford, Frank Sinatra, Louis Armstrong, Carmen Miranda, Fred Astaire, and Benny Goodman performed on stage. In all, the biggest and brightest stars in Hollywood showed up before the men — and some women — shipped off. Davis kept it all together through its grand opening in October 1942 until the doors were closed — after the war came to a victorious end — on Thanksgiving Day, November 22, 1945, by enforcing her codes of decency, no fraternization between entertainers and servicemen, no alcohol, and no racial segregation.

Three hundred volunteers spread out over two shifts staffed the canteen during the nightly hours of 7 p.m. to midnight and Sundays from 2 to 8 p.m. When the Hollywood Canteen closed, the organization's $500,000 surplus was donated to veterans’ relief funds. According to the national World War II Museum, “more than 3,000 volunteers distributed three million packs of cigarettes and served six million pieces of cake, 125,000 gallons of milk, and nine million cups of coffee. The Hollywood Canteen had hosted and entertained nearly four million service members.”

It was a resounding success. Warners made an eponymous fictional picture of the Canteen named, well, "Hollywood Canteen.” Unabashedly patriotic and a showcase of Warners’ stars, including Bette Davis, Joe Cantor, Jack Benny, and Joan Crawford, with appearances by many others, the popular song-and-dance number “You Can Always Tell a Yank” was performed by Dennis Morgan and Joe E. Brown with Jimmy Dorsey and His Orchestra. “You can tell a Yank, By the way he eats a frank, By the way he fights for the Bill of Rights, And the right to love a girl in tights...”

Providing entertainment, whether through the Hollywood Victory Committee, the Canteen, or the United Service Organization (USO), isn’t Hollywood’s only or most important contribution to America’s past war efforts. Direct service has always been the greatest sacrifice during times when these men and women could stay home. In addition to Gable, director John Ford reenlisted in the Navy and was wounded at Midway. Humphrey Bogart enlisted in the Navy in 1918, and was too old to rejoin the Navy during WWII, settling for the Coast Guard Temporary Reserve and patrolling the California coast in his yacht Santana. A few of the many serving overseas included Eddie Albert, Ernest Borgnine, Paul Newman, Henry Fonda, Audie Murphy — the most decorated soldier in American history, and Jimmy Stewart, who was “appointed Operations Officer of the 453rd Bomb Group and, subsequently, Chief of Staff of the 2nd Combat wing, 2nd Air Division of the 8th Air Force. Stewart ended the war with 20 combat missions. He remained in the USAF Reserve and was promoted to brigadier general on July 23, 1959. He retired on May 31, 1968.”

Even Bernice Frankel, more popularly known as Golden Girl Bea Arthur, put in her time — serving in the United States Marine Corps. She enlisted in the USMC Women’s Reserve just shy of her 21st birthday, eventually attending the Motor Transport School and working as a dispatcher and truck driver.

There have been others since — Elvis Presley, Morgan Freeman, Drew Carey, Chuck Norris, and Adam Driver. But they are men among Men. The ones America calls heroes and to whom we have a debt that cannot be repaid through free dances and donuts or once-a-year acknowledgments mixed in with weekend mattress sales. The men and women who are the real stars said goodbye and never came home. They left farms and family businesses, schoolhouses, and city jobs. They understood the world perhaps better than we ever could: the sacrifice of becoming a memory. They were boys who became men on the battlefield but would stay someone’s boy forever. So, while we thank those who committed themselves to defending the last greatest hope in the world, we honor and grieve those who remain living as that hope’s eternal flame. The Dreamers who never got their Dream.

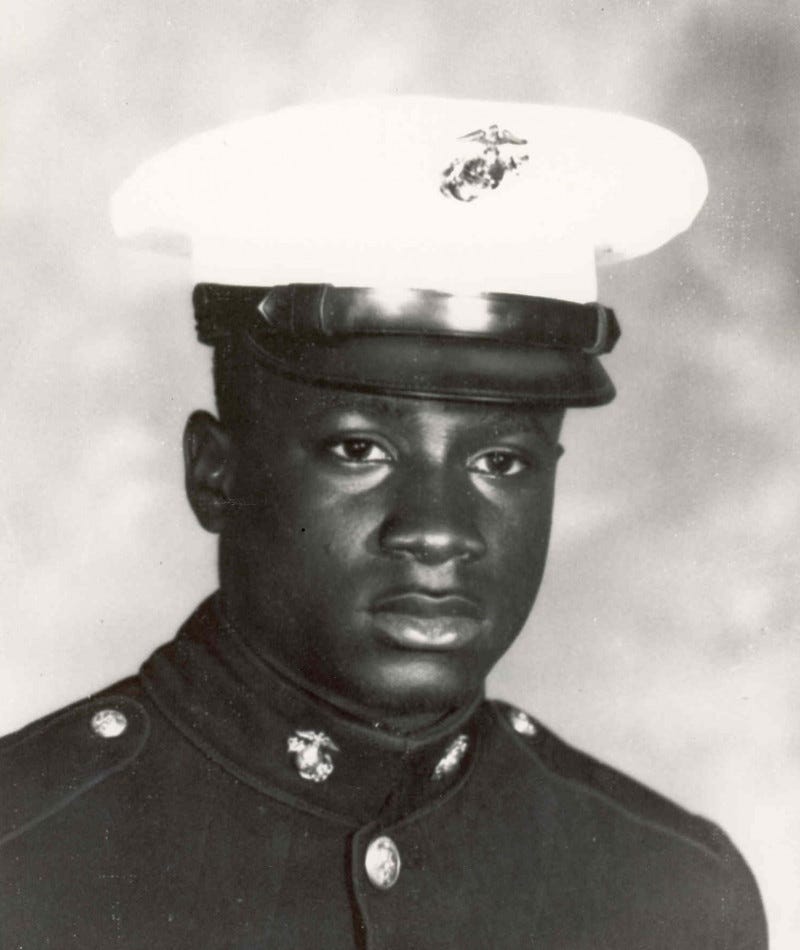

Men like USMC Private First Class and Medal of Honor recipient Robert Jenkins, Jr.:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a machine gunner with Company C, 3d Reconnaissance Battalion, in connection with operations against enemy forces. Early in the morning Pfc. Jenkins' 12-man reconnaissance team was occupying a defensive position at Fire Support Base Argonne south of the Demilitarized Zone. Suddenly, the marines were assaulted by a North Vietnamese Army platoon employing mortars, automatic weapons, and hand grenades. Reacting instantly, Pfc. Jenkins and another marine quickly moved into a two-man fighting emplacement, and as they boldly delivered accurate machine-gun fire against the enemy, a North Vietnamese soldier threw a hand grenade into the friendly emplacement. Fully realizing the inevitable results of his actions, Pfc. Jenkins quickly seized his comrade, and pushing the man to the ground, he leaped on top of the marine to shield him from the explosion. Absorbing the full impact of the detonation, Pfc. Jenkins was seriously injured and subsequently succumbed to his wounds. His courage, inspiring valor, and selfless devotion to duty saved a fellow marine from serious injury or possible death and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

Please follow the link for Pfc. Jenkins, above, as it tells his inspiring — and too short — life story.

Very nice piece, Jenna. Very appropriate to remind us to set aside politics and petty arguments to remember those of our family, friends and neighbors who sacrificed all.

"Time will not dim the glory of their deeds."

- General John J. Pershing

A wonderful piece. I wanted it keep going. You are an old soul, flying over the treetops of time. I can tell so much sweat equity went into it. You done good. If there’s more to this, you’ve got readers.