Little morsels dressed up in foil wrappings: red-hots and taffy, sticky rum-tumblers, sour humdingers and bitty ring-tinglers. The gobs of chocolate smoothers and nut-coated cracklers, gleaming rainbow pips and soft melting goobers. Candy. Not just any candy, but the candy of childhood with simple tastes and bright-eyed cheer that glowed like the rising moon spreading magic light upon the mysterious world waiting, waiting for us to grow up.

We all joke about Werther’s Original. The buttery caramel hard candy in the shiny gold wrapper. Popularized with the blue-haired crowd so much so even the company leaned into it with its advertisements. But there were others. Crème mints and butterscotch disks. Black licorice. Strawberry bonbons — the little red candies with a wrapper miming a real strawberry. Where did they come from? There is no mystery with Werther’s. Every drug store in America is well-stocked with them. But the little red sweets, they must come from some Grandparent’s Emporium along with clear plastic hair bonnets, Aqua-net hair afixer, and wrap-around sunglasses that fit over regular glasses. Probably right next to the nude-colored Rockport shoes.

Then there is Christmas candy.

Oh, but what of Halloween, you might say, or Valentine’s Day or Easter? We-ell no.

Halloween is wrapped in the pursuit. Children rush around with their buckets and bags and pillowcases. Valentine’s Day is a mere obligation and, at most, a transactional affair. Easter doesn’t carry the same lingering preciousness of wonder. It’s a day outlined in seriousness. Christmas, though, grants us unhindered wonder. We are given permission to cherish the smallest miracles with the oversized splendor of a thousand trumpets declaring it so.

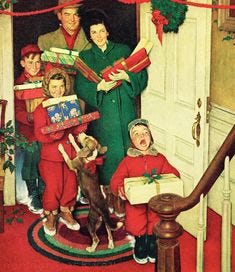

The candy at Christmastime is like the season itself: all dressed up in a little bit of special sparkle and tradition. That in this little confection of sugar or chocolate is a lifetime of memories. In the hectic bustling of modern life — when we have more convenience but much less time — we can see how something as simple as a candy cane lights up the eyes of a child.

Maybe it’s a bit of homemade fudge, a bit of caramel, or a cherry cordial. Seeing the Hershey Kisses ringing out “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” decked in red and green foil. Still “Christmas” despite corporatist collective shrugging of the term. Chocolate coins and lifesaver books. Candy canes of all colors and flavors and sizes, maybe even hung on a tree, tempting little quick fingers that can reach just so. The lasting things endure.

So we buy the candy canes and make the fudge and try our damnedest to replicate the sugar cookies or the spiced cider or sewn holly buttons or the marshmallow fruit salad. We never get it quite right. But we do it because it was done for us when we were small and full of wonder, and when Christmas magic spread out before us with the moonlight, one tiny miracle leading to the greatest miracle, and it was all for us.

We go back to those memories because we cannot go back to what was. Try as we might to capture the magic, it is a child’s magic. It is ours to give and it belongs to them. That is the sacredness of the season and the core of belief in sacred and magic things. A parent’s love for their child. Keeping the magic alive as long as possible and keeping it precious.

Charles Dickens reminds us of this in his classic story “A Christmas Carol” first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843: “For it is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty Founder was a child Himself.”

I don’t remember many gifts I was given through the years. But I remember the family gathering around my parents' modest dining room table with too many seats and not enough space and us kids waiting impatiently as the grownups sat talking for an impossibly long time, telling the same stories we heard last year and the year before.

My great aunt sat at one side, her tiny, aged frame under a black velvet beret pinned on top of primped white curls. She wore gloves and had one good purse, and out of it, she took one box of ribbon candy and one box of candied fruit slices. And I never saw such fancy, delicate, glimmering things except for my grandmother’s costume jewelry. But this was Christmas and it was special and she brought them every year until she died.

Over the years the places at the table thinned and dinner didn’t take quite so long. And us kids grew up and spread out, and “We can’t wait to see you” turned into, “Maybe we’ll see you next year.”

The three of us now have our own families — married and kids. But in between the pauses of stories and remembrances now gathered around a new table with more chairs again, I’m back to that house we grew up in. All of us together. Sitting in hard chairs around the kitchen table covered with peeling linoleum. At a writing desk, a telephone with an impossibly long cord coiled against itself. Or crammed side by side with blankets in the basement. Together. Believing it will always be this way until one day it isn’t.

And I want to go to that little girl and shake her and look her full in the eyes and tell her to hold onto this with her whole life. That no this will never last and it will never last sooner than you know. And your heart will ache at it — the loss of it. Because you will do stupid things and say stupid words and you destroy the lasting of it — the innocence of it — and you can never take it back. You can never go back. So today I’m thankful for all the blessings that got me through, but it’s haunted by the grief of what was lost along the way.

This is where tradition enters and soothes the ache. We can never go back but we can gift the magic to the small hearts and bright eyes of our kids. It’s how the magic of Christmas never fades.

Introducing his 1939 radio production of “A Christmas Carol” (sponsored by Cambell’s Soup!) on the Columbia Broadcast System, producer and narrator Orson Welles says,

When Charles Dickens presented this little story to the world almost a hundred years ago, he found an instant response in the hearts of people everywhere who saw in it their favorite fictional chronicle of what Christmas is, and what Christmas means to all the simple people of the Earth. From the day of its first printing, families have been innumerable in which there has remained unbroken the tradition that the reading of “A Christmas Carol” was an item indispensable to a proper observance of the most important of days.

It is the American way, as we know, to establish traditions quickly where popular instinct and sentiment pronounce them sound.

This production starred Lionel Barrymore as Ebenezer Scrooge. Barrymore might be most well known (and detested?) for his role as Mr. Henry Potter in Frank Capra’s 1946 classic film, It’s A Wonderful Life, a Christmas viewing tradition in its own right.

There will always be the naysayers and ninnies and Bah-humbug Scrooges waiting for the first glimmer of tinsel or note peppermint and holly in the air to beat tradition and mystery with the club of pretentious reason-moralization. Fairytale they say. Rank consumerism built on pagan rites or some such nonsense. They deprive themselves of enchantment to justify their unhappiness. They dismiss the past, tradition, and spirit because they can’t bear to face the transformation that may follow. This sentiment is the embodiment of Ebenezer Scrooge.

For that, G.K. Chesterton carried on the traditional wonderment of Christmas just as Dickens, perhaps more openly in his celebration. And, like Dickens, aligned it with the special heartfelt innocence that children carried with them for the spirit of it all. He had an answer to the Scrooges of his time, and ours in his essay “The Red Angel” published in Tremendous Trifles, 1909:

I find that there really are human beings who think fairy tales bad for children. I do not speak of the man in the green tie, for him I can never count truly human. But a lady has written me an earnest letter saying that fairy tales ought not to be taught to children even if they are true. She says that it is cruel to tell children fairy tales, because it frightens them. You might just as well say that it is cruel to give girls sentimental novels because it makes them cry. All this kind of talk is based on that complete forgetting of what a child is like which has been the firm foundation of so many educational schemes. If you keep bogies and goblins away from children they would make them up for themselves. One small child in the dark can invent more hells than Swedenborg. One small child can imagine monsters too big and black to get into any picture, and give them names too unearthly and cacophonous to have occurred in the cries of any lunatic. The child, to begin with, commonly likes horrors, and he continues to indulge in them even when he does not like them. There is just as much difficulty in saying exactly where pure pain begins in his case, as there is in ours when we walk of our own free will into the torture-chamber of a great tragedy. The fear does not come from fairy tales; the fear comes from the universe of the soul.

The timidity of the child or the savage is entirely reasonable; they are alarmed at this world, because this world is a very alarming place. They dislike being alone because it is verily and indeed an awful idea to be alone. Barbarians fear the unknown for the same reason that Agnostics worship it– because it is a fact. Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.

Exactly what the fairy tale does is this: it accustoms him for a series of clear pictures to the idea that these limitless terrors had a limit, that these shapeless enemies have enemies in the knights of God, that there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear.

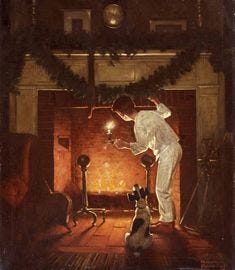

We don’t pass these traditions on or instill the innocence owed to our children or try to recreate the simple nature of our childhood for selfish reasons or self-preservation or for the search for forever youth. It's because the dragons and bogies will come sooner or later. The world naturally conjures them. And when the events in the world around us are chaotic or the problems too big and overwhelming, simple things like a treasured story, a morsel of precious candy, or a beloved Christmas carol can make the world small again — and simple again.

I can still call my parents — still in that same house with the same dining room table, “Hi yes, it’s me. Merry Christmas. Yes, we’ll be there and yes, I’ll bring the ribbon candy.”

So it is with the smallest simple joys that create a season with an overabundance of it.

The House of Christmas

G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936)

There fared a mother driven forth

Out of an inn to roam;

In the place where she was homeless

All men are at home.

The crazy stable close at hand,

With shaking timber and shifting sand,

Grew a stronger thing to abide and stand

Than the square stones of Rome.

For men are homesick in their homes,

And strangers under the sun,

And they lay on their heads in a foreign land

Whenever the day is done.

Here we have battle and blazing eyes,

And chance and honour and high surprise,

But our homes are under miraculous skies

Where the yule tale was begun.

A Child in a foul stable,

Where the beasts feed and foam;

Only where He was homeless

Are you and I at home;

We have hands that fashion and heads that know,

But our hearts we lost - how long ago!

In a place no chart nor ship can show

Under the sky's dome.

This world is wild as an old wives' tale,

And strange the plain things are,

The earth is enough and the air is enough

For our wonder and our war;

But our rest is as far as the fire-drake swings

And our peace is put in impossible things

Where clashed and thundered unthinkable wings

Round an incredible star.

To an open house in the evening

Home shall men come,

To an older place than Eden

And a taller town than Rome.

To the end of the way of the wandering star,

To the things that cannot be and that are,

To the place where God was homeless

And all men are at home.

To all of you who signed up for these little observations and ramblings from a stranger — a pilgrim — finding her way in a strange world ever stranger but still searching for the familiar and meaningful, I offer my sincere thanks. I hope this post finds you able to carve some time and place for savoring the little miracles in your life. May they outlast us all.

Sincerely, Jenna

Desolation and hope reside on the same contour this time of year. Haggard nailed it: If we make it through December everything’s going to be alright I know.

Simply beautiful.