We Are More Than An Idea

America lies at the end of wilderness road.

I guess in Hollywood or in some publishing office desk drawer, there’s a perfect story waiting to be told. Maybe it was dreamed up in some fever-manic pixie dust haze that woke up the writer in a daze and, with possessed hands, scribbled, like lightning striking that lone oak in the high hills, immediately setting it ablaze and smoldering out in a heap of smoke.

Or it was carefully curated, day by day, painstakingly unraveled from the imagination of a lone, anonymous genius who spends his days riding to work with eyes glazed over, in denial of a horrible job working with petty, horrible people, and receiving nothing but silent ridicule by his very presence in the place. His only respite is his little office with the flickering lights that cast a pasty aura on any half-living thing.

But there is a story there. A human who dreams of a way out of his present state of loss and lostness. Where the unbearable truth of life is that it keeps going on without any answers. Dreams where the plot is just out of reach; ceaseless wind without pausing for breath; the moon that has nowhere to go.

There is no certainty except the perpetual gnawing at the edges of longing. But for what, and for whom, and for when we cannot see or hear or run to.

Before, I thought about finding an anchor to things that last. Maybe it was a hope that I had that things would last — or that I could will them into a perpetual life not apart from my own in a grasping attempt at finding solid ground. And I talked (or wrote) myself into it and am encouraged by the wonderful stories readers shared. But now what?

Individuals and families can carry on these little things — these smallish trinkets that get dusted off for special occasions, like a Christmas ornament or company dishware, or that have a home on some high shelf away from little hands until they’re passed down to people who have no recollection of the passed-down story that haunts such a thing. The memory beneath it fades along with its preciousness.

Even pictures become nameless faces that stare back in silence.

But what about the things that define our society? What of the things that we destroy that have held us together, however perilously and with a loose fragility, but together, nonetheless?

Two things I have an endearing love for are the American Frontier and Mid-20th Century Americana. Both eras represent a great time of growth, a persistence through change (and often hardship), and the American Spirit borne of optimism, bold adventure, and hard determination outlined by vague recklessness that allows for limitless imagination. It cries out: “Try and catch us, define us, and put us in a box; we’ll defy you every time.” But we’ve left these things to wither and decay and milled the roads of American Greatness without thinking of how the following generations would find their way, how they would understand the tough path that was forged before them, or how we even build these roads going forth.

Part of this is the stories we pass down. Part of it is found in the monuments we build.

The American Epic was started in the Western frontier and lasted through the wars and famines suffered in the bones of a rising nation that came into its own youthful vigor of the 20th century.

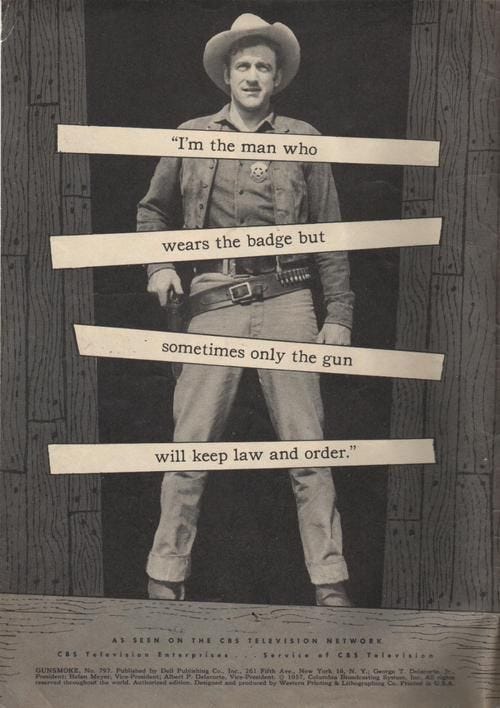

T.K. Whipple’s anthology “Study Out the Land” contains an important essay — a criticism and lamentation of the lack of Western literature, or rather the proper and artful telling of the tales of the Old West, apart from the Zane Grey adventure stories idealizing the American frontier. The essay, “The Myth of the Old West,” reveals the true treasure in these stories from which the American ethos is rooted and where the haunting of past ghosts lingers around the edges of popular culture, if not trivialized and caricatured grotesquely and unfairly, working against the purpose of these stories as they shape our national identity and outlook and acts as an anchor in a chaotic, spasmic world.

Maybe Whipple needed to wait a few decades for Larry McMurtry’s “Lonesome Dove.” In that epic Western (American!) novel, McMurtry includes this partial excerpt from “Myth” in the novel’s epigraph:

It is high time for the people of the United States to rebel against their recorders, and demand that some meaning be extracted from material so rich in significance as that concerning men or the children of men who left civilization and traveled the wilderness road. What really happened to these men? All America lies at the end of the wilderness road, and our past is not a dead past but still lives in us; thus the question is momentous. But it has not been answered. Our forebears had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in the civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live; and what they lived, we dream. That is why our western story still holds us, however ineptly it is told.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” wrote Joan Didion in the opening lines of her essay “The White Album.” A bold statement from a physically unimposing figure who has had an outsized influence on the literary world and the American consciousness. While that essay was a profession of her doubt about the stories and myths that she was raised on, it was an admission of the importance of these myths. Since ancient times, people have drawn great meaning and inspiration from their families, histories, and culture, and the desire to preserve these connections. The stories that emerge from our history — the myths — help bring order to a chaotic human existence and sharpens the focus of what our expectations are for the future, for our country, and for ourselves. We find our place — through time — in the order these stories provide.

What if no one is left to tell the stories? What if we don’t believe in them anymore? We’re on the verge of a breakdown in mistrust and disbelief that it comes full circle in a damaging way. We believe in what we’re told, we believe in what we want to see rather than what we used to know by faith, intuition, and from the wisdom of traditions and mores and virtues. Now, it’s about belonging and allegiances and finding a hiding space among followers. Swear your oaths to the data! There are no more stories.

It is similar when we look at the constant destruction of our mid-20th-century monuments: The buildings that signified the booming creativity, productivity, and striving that was suddenly open to a nation emerging as a world leader with seemingly unlimited potential and the boldness to go forth with vision and imagination.

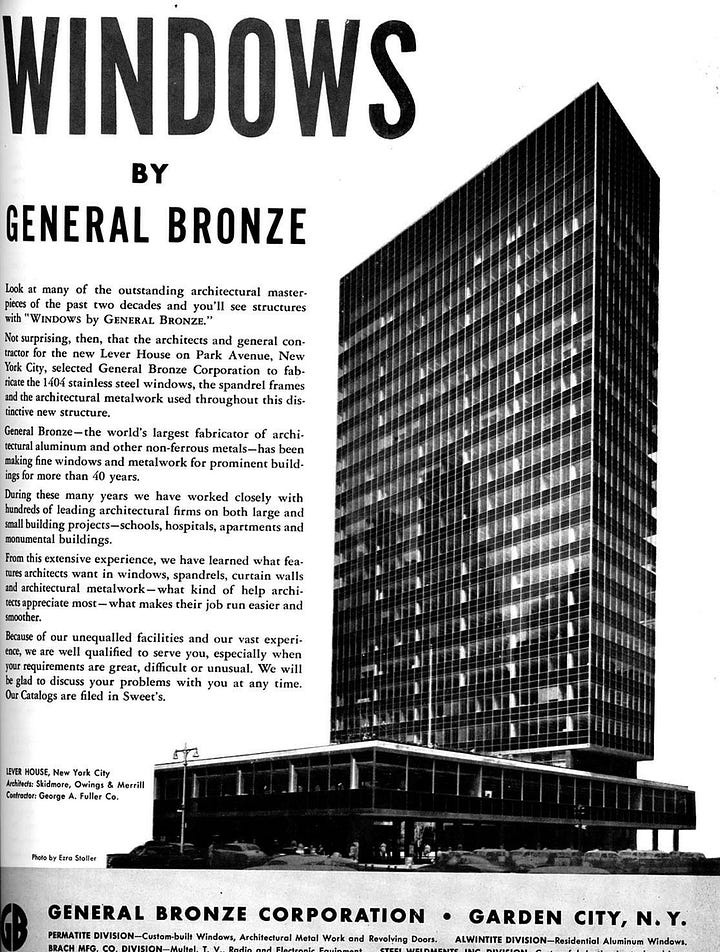

The Ford World Headquarters building, popularly known as the Glass House in Dearborn, Michigan, was the administrative headquarters of the Ford Motor Company until this year. It was designed by architects Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois, both with the firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. In an article for RealClearPolitics in 2008, George Will described the building as having “the sleek glass-and-steel minimalism that characterized up-to-date architecture in the 1950s, when America was at the wheel of the world and even buildings seemed streamlined for speed.” The country reached “a peak of American confidence.”

The Glass House is being demolished and replaced by a sprawling campus that is indicative of the decentralized, anti-focus mentality of today’s soft-corporate visions. The company behind the new meandering grounds is the Norwegian architecture firm Snøhetta.

In addition to the Glass House, Pennsylvania native Natalie de Blois also designed the Pepsi Cola Headquarters, Lever House, and the Union Carbide Building in New York City and the Equitable Building in Chicago. All monuments to mid-20th-century aspirational vision.

The Union Carbide Building at 270 Park Avenue (later known as JPMorgan Chase Tower) was part of a larger post-war movement that signaled America’s burgeoning economic and cultural rise, and its leadership as a global power. A 1996 New York Times article described America’s First City and its aesthetic:

Holly Golightly looked wistfully on the face of Manhattan as she prepared to depart for Rio. “Years from now, years and years, I’ll be back,” she declared. “Me and my nine Brazilian brats. I’ll bring them back, all right. Because they must see this.”

“This” in the 1961 movie “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” was not Central Park, the Brooklyn Bridge, or Rockefeller Center. It was the steel-and-glass corporate canyon of postwar Park Avenue.

Those International Style skyscrapers — Lever House, the Seagram Building, the Union Carbide Building — epitomized New York at the peak of its economic might and worldwide prowess.

Gordon Bunshaft and de Blois also designed the Lever House. It successfully merged the modern, streamlined aesthetic with a functional artistic style and quickly became home to quintessential New York artists. By 1977, the 25th anniversary of its opening, the building had housed 250 art exhibits. Under threat of demolition in the 1980s, it received support from nationally renowned preservationists as well as Jackie Kennedy Onassis and New York Mayor Ed Koch. It eventually received protection as being on the U.S. National and New York State Registers of Historic Places.

I’ve written before about Googie and its quick rise and tragic disappearance. Bland-tastic nonsense is on the rise — the favorite aesthetic of corporate consultants and unimaginative branding “experts” who see a colorful, vibrant, confident world full of stories and history and demolishing it on turquoise boomerang and starburst after another. And it’s leaked toxic homogeneity gray-scale nothingness into everything from Cracker Barrel to state flags.

This is more than logos and office buildings and tales of the cowboys and adventurers. It is America’s story. It is part of the foundation of a nation that identifies with the myths of its own creation to forge a path into the future with a leadership mindset and optimism and hope.

Inside these buildings, empires were dreamed about and built. Men and women showed up at offices and did the daily tasks and interacted with each other (in real life!) to form a collective experience and broadcast it through their lives — in taxicabs, subway cars, and chrome-trimmed automobiles, and eventually to space and the moon. They built financial infrastructure and families. They went to movies and watched Gunsmoke and took road trips. They lived through wars overseas and in our backyard. And it was all woven into the American fabric.

Writer and professor of history Wilfred McClay writes on Oct. 21 at the University of Texas at Austin’s Civitas Institute about the often competing but complementary philosophies of America as an idea versus a common creed in his essay “Creed, Culture, and American Memory”:

There can be no doubt that a specific idea of America forms a key element in the makeup of American national self-consciousness. But it is far from being the only element. There is also an entirely different and entirely necessary set of considerations in play. As the French historian Ernest Renan insisted in his 1882 lecture “What is a Nation?” a nation should be understood as “a soul, a spiritual principle,” constituted not only by present-day consent but also by the dynamic residuum of the past, “the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories” which form in the citizen “the will to perpetuate the value of the heritage that one has received in an undivided form.” These shared memories, and their passing along, form the core of a national consciousness.

A nation is not only an idea, in this view. It is, as Renan argues,

“the culmination of a long past of endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion. To have common glories in the past and to have a common will in the present, to have performed great deeds together, to wish to perform still more—these are the essential conditions for being a people.… A nation is therefore a large-scale solidarity, constituted by the feeling of the sacrifices that one has made in the past and of those that one is prepared to make in the future.”

Performing great deeds together, remembering travails borne together…. These mark something different from an “idea.” They mark a very particular force, a sense of belonging and membership, of an embrace of the past in all its human complexity ... Our nation’s particular triumphs, sacrifices, and sufferings — and our memories of them — bind us together, precisely because they are the sacrifices and sufferings, not of all humanity, but of us alone.

What stories are we telling ourselves? What monuments are gazing up at in wonder — and what do the things we build now tell us about ourselves? Are these the things that last? Only if we believe in them.

This is an excerpt from Charles Portis’s essay collection published in the Oxford American documenting his travels across the American Southwest. “Motel No. 1”:

Back when Roger Miller was King of the Road, in the 1960s, he sang of rooms to let (”no phone, no pool, no pets”) for four bits, or fifty cents. I can’t beat that price, but I did once in those days come across a cabin that went for three dollars. It was in the long, slender highway town of Truth or Consequences, New Mexico.

Thanks to my brother for recommending this collection. I’ve been a longtime Portis fan, and this collection contains his best work. A master storyteller and literary monument builder whom T.K. Whipple would approve.

Sincerely, Jenna

Jenna,

I really enjoyed this essay. I hope we can find our way back to shared pride and shared community.

Wonderful writing as always. Thank you for keeping the American stories and myths alive!

Great insight and I share your hope that America can move forward toward beauty and style and build a connection to our past. Trump is right, beautiful buildings are inspirational and I hope he is successful in starting a trend in architecture.

America didn't get the opportunity to steep in our culture for hundreds or thousands of years like Italy, Norway, or the Far East before the world started changing rapidly and becoming global. Laura Ingalls died with linoleum kitchen floors in the same year Sputnik hit orbit. Maybe the great race forward supplies our strength, but the payment is our past?

You are making the good things last. Your family and friends must love the richness you bring to their lives.