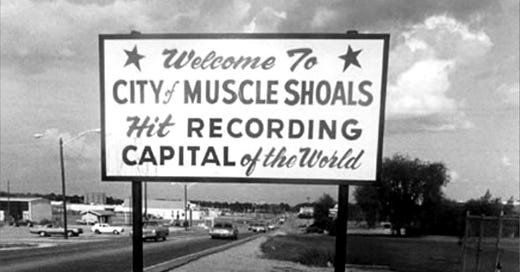

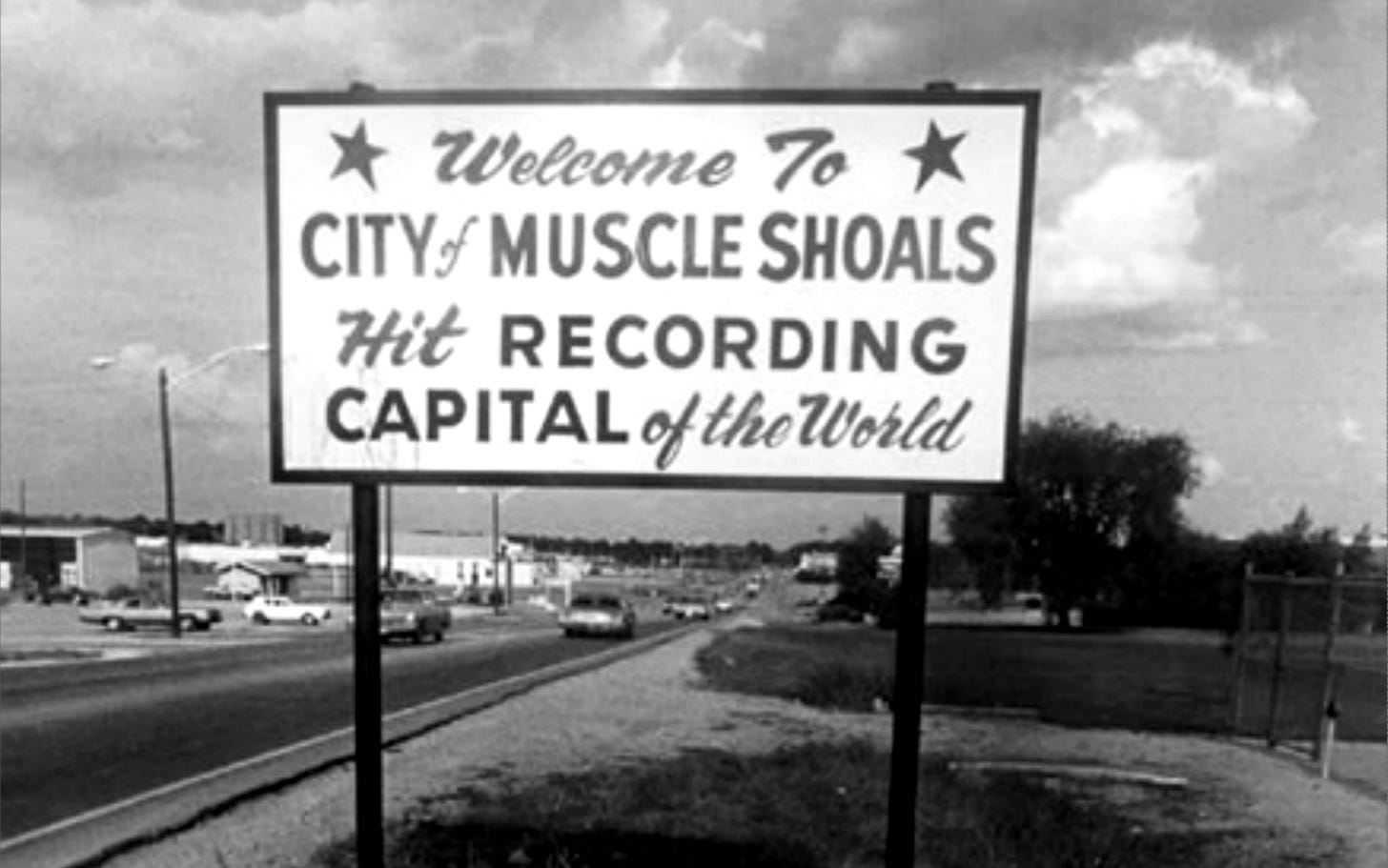

The Sound of Americana in Muscle Shoals

Defying divisions of class, race, and sound on the way to the American Dream.

"The river has great wisdom and whispers its secrets to the hearts of men."

—Mark Twain

Wilson Pickett’s 1966 dynamic hit “Land of 1,000 Dances,” Percy Sledge’s passionate single “When a Man Loves a Woman,” The Rolling Stone’s wayward Western-esque “Wild Horses,” and Lynyrd Skynyrd’s purposeful meandering “Free Bird”: undeniable hits that both defined and defied eras in music and culture that could only be born of a sound as uniquely genuine, funky, and soulful as the land from which it rose: Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

This is the wondrous thing about America — greatness can be realized from the unlikeliest places, by the most unlikely people and personalities, despite enormous odds and “very smart people” who believe otherwise. But that is the story of an unassuming town off the muddy banks of the Tennessee River in northern Alabama; of a man who grew up in crushing poverty — in a house with a dirt floor, no toilet or bath, sleeping on a bed made from the straw he pulled from the ground himself; and a time when the energy would explode like a thousand lightning strikes caught in a drumbeat: the type of legendary tale that reaches the outer bounds of imagination, destined for immortality in the halls of Americana.

The Shoals was one piece of the magic that carried success and pain and life like a river itself. The biggest, brashest, most successful record labels and artists — Columbia, RCA, Atlantic, Warner, Capitol, Motown — were synonymous with New York City, Los Angeles, Detroit, and Nashville. Florence Alabama Music Enterprises, or FAME Studios, was the creation of a man motivated by a seemingly primitive need for success. The son of a sawmill worker brought up in the outskirts of the three-town community that comprised the Shoals on the banks of the Tennessee (Muscle Shoals, Florence, and Sheffield), legendary producer Rick Hall was driven by raw will and a need to outrun the shadows of personal tragedy and prove to the world that he could beat his fate.

In 1961 Hall would produce “You Better Move On,” a song written and sung by a bellhop from nearby Sheffield, Arthur Alexander that went on to number 24 on Billboard’s Hot 100. On January 10, 1964, The Rolling Stones released their version, just a few weeks after The Beatles popularized Alexander’s “Anna (Go to Him).”

The real catalyst was found in the voice of Percy Sledge in 1966 — another Shoals local who matched the humble and poverty-stricken beginnings of Hall and Alexander. Sledge grew up picking cotton, singing in the fields to pass time, and later taking a job as an orderly at the Sheffield hospital. Hall got hold of Sledge’s original recording of “When a Man Loves a Woman” — the first time Sledge set foot in a studio — and instantly recognized the sound of success. He played the single over the phone for Atlantic Records’ producer Jerry Wexler in New York and a chart-topping hit was born.

A parade of local talent would cross the threshold of the FAME Studios, but after the Sledge’s money making hit, bigger acts were on the horizon.

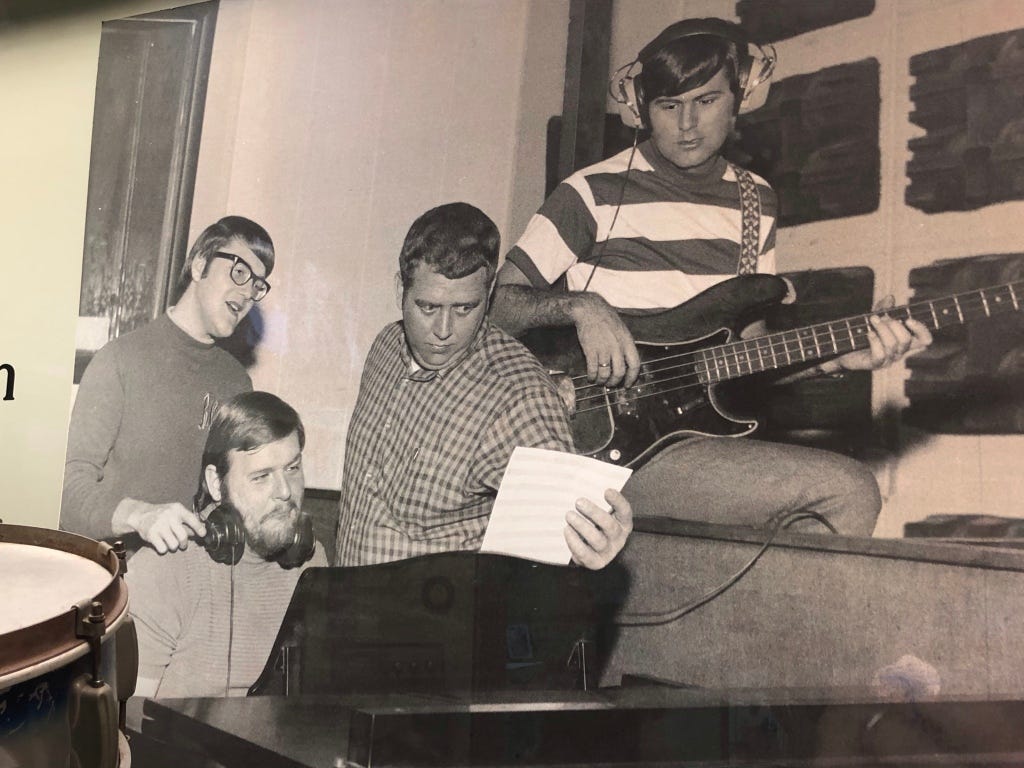

Wexler, having been cut off from Memphis-based Stax Studios (and the session band, Booker T. and the M.G.’s) took rising star Wilson Pickett to Muscle Shoals and let Hall shoot his shot. The original FAME session musicians left for Nashville and were replaced by a group of four local white kids who later be known as “The Swampers.” With Jimmy Johnson on guitars, David Hood on bass, Roger Hawkins on drums, and keyboardist Barry Beckett, what began as a ripple through the airwaves quickly turned into a flood of unmistakable and inescapable music: the Muscle Shoals sound. And the hits rolled off the line.

In the definitive 2013 documentary Muscle Shoals (a brilliant and engrossing film I highly recommend), Wexler says "There's just something that leaps out of a record — I call it the sonority of the record. It's the way the sound impacts on your ear, instantly. To me that's the magic ingredient. The Rolling Stones had it, the Beatles had it and Muscle Shoals had it."

"Mustang Sally," "Funky Broadway" and "Land of 1,000 Dances” were followed by a career-defining visit from Aretha Franklin. Wexler signed her with Atlantic after a number of unproductive years at Columbia where she was pigeonholed in easy listening or Gospel-oriented sounds. But it was at FAME with Hall and The Swampers that the Queen of Soul would finally earn her crown. A violent confrontation between Hall and Franklin’s manager and then-husband Ted White ended the session at FAME prematurely, but the sound was already established.

Coming to Muscle Shoals was the turning point. That’s where I recorded ‘I Never Loved a Man,’ which became my first million-selling record. So absolutely it was a milestone and the turning point in my career.

Mick Jagger adds of Franklin’s epiphany at FAME: “They got Aretha to record a much more funky kind of style in Muscle Shoals. It was really the essence of her.”

The abrupt end of the Franklin session was also the end of the relationship between Hall and Wexler. The Swampers would eventually turn entrepreneurs in their own right, split with Hall and open their own studio, Muscle Shoals Sound Studio across town. But the sound never died. It was ingrained in the area — something about the anonymity and the wilderness, the hardship, struggle, pain, and sacrifice cut through the land like the river itself, lending a guttural, soulful richness that couldn’t be replicated in New York streets or Los Angeles hills. What emerged from the depths of that river was interpreted by a group of white kids who were raised on R&B and rock and roll. Like magic, they created a sound. Franklin called it “greasy.” “Musicians feel something special in Muscle Shoals — they're isolated and connect with the soil and the river," says Sledge in the film. "When you're relaxed, you open up and let things out."

What was “let out” was what drew in some of the most iconic and important musicians in history: Etta James, the Staple Singers — Bob Dylan recorded his albums “Slow Train Coming” and “Saved” — Otis Redding, Steve Winwood, Clarence Carter, Candi Staton, Bob Seger, Rod Stewart, Levon Helm, and Joe Cocker. Although a commercial failure, Cher’s 1969 album “3614 Jackson Highway” was produced at Muscle Shoals Sound with the building featured on the album’s cover.

Coming off a successful North American tour in 1969, The Rolling Stones began an intense three-day recording session at Muscle Shoals Sound in December for what would be their triple-platinum album “Sticky Fingers.” There they cut “Brown Sugar,” “You Gotta Believe,” and “Wild Horses,” (an earlier version of “Horses” was written by Keith Richards and Gram Parsons of The Flying Burrito Brothers).

Of the historic, fierce, and shorts session, Richards and his Stones bandmate Mick Jagger had this exchange:

Richards: I thought it was one of the easiest and rockingest sessions that we’d done. I don’t think we’d been quite so prolific ever. I mean we cut three or four tracks in two days, and that, for the Stones, is going somewhere. We left on a high with “Brown Sugar.” We knew we had one of the best things we’d ever done.

Jagger: The thing about “Brown Sugar,” it had this sound, it was quite distorted. It was pretty funky, you know. That was the whole idea of it.

Richards: I always wanted to go back there and cut more, then shit happened, so we ended up in France in a basement doing “Exile on Main St.” there, but otherwise, “Exile” would probably have been cut in Muscle Shoals, but politically, it wasn’t possible. I wasn’t allowed in the country at the time. Those sessions were as vital to me as any I ever done. I mean, all this other stuff, “Beggars Banquet” and the other stuff we did, “Gimme Shelter,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” but I’ve always wondered that if we’d cut them in Muscle Shoals, if they might not have been a little bit funkier.

But that was all part of the magic and what made the Muscle Shoals story quintessentially an American story. Aside from the meager and humble beginnings of the artists and architects who came from this place and who would go on to define a sound and era, they defied the fiercely divisive political and cultural environment exploding around them. It was the music they created that helped bridge the color divide. This was a state in which the Democrat governor, George Wallace, declared in his 1963 Inaugural address, “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny...and I say...segregation now...segregation tomorrow...segregation forever.” But for those musicians, in those recording studios, there was no black or white. Hall, like his friend Sam Phillips of Sun Records fame, worked with mostly black artists. He just wanted to work with the best.

Looking back, Clarence Carter says, “You just work together, you never thought about who was white and who was black. You thought about the common thing and it was the music.” “We were color blind. There was never any situation that came up in the studio here ever about ‘You’re black and I’m white.’” Says Hall.

Swamper guitarist Jimmy Johnson: “I remember when Paul Simon called Stax Records, talked to Al Bell and said, ‘Hey man, I want those same black players that played on [The Staples Singers] “I’ll Take You There.”’ He said, ‘That can happen, but these guys are might-ty pale.’”

Bono, U2’s frontman is featured prominently in the documentary says, “People have arrived at Muscle Shoals expecting to meet these black dudes, and they’re a bunch of white guys that look like they worked in the supermarket around the corner.”

The music allowed people — gave them permission to set their differences aside; to just enjoy the music for enjoyment’s sake and appreciate the craftsmanship, the genius, the talent, the rip-roaring funky soul sound coming through the speakers, flashing off the vinyl and no one knew who was what color or creed or from what kind of background. There was a universal thrill and passion evoked by these musicians, unlike anything that had been heard before. One could forget politics and race and tribalism. What a contrast to today where cultural appropriation and intense identity politics has revived feelings of racial animosity and deepened division where once they were mending.

Music historian Charles Hughes writing for Soul Sides in 2006 describes Muscle Shoals:

…the scene’s contribution to soul music, specifically, is fascinating in the way that it demonstrates interracial exchange in the creation of music that was soulful, funky, and very conscious, even celebratory, of its blackness. White rhythm sections combined with integrated horn sections to play on songs by primarily white songwriters sung by black artists…

Even as American music was about to reform and undergo yet another transformation, Muscle Shoals was at the start of it. Duane Allman — a long-haired gypsy-looking vagabond — camped out in the FAME parking lot in a pup tent for his shot. And it came with Wilson Pickett, as unlikely a pairing as one could imagine, but together it was alchemy, the greatest guitar Eric Clapton ever heard, and the birth of Southern Rock. As Randy Poe writes in his 2008 biography of Allman, Skydog: The Duane Allman Story,

“Pickett came into the studio,” says [Rick] Hall, “and I said, ‘We don’t have anything to cut.’ We didn’t have a song. Duane was there, and he came up with an idea. By this time he’d kind of broken the ice and become my guy. So Duane said, ‘Why don’t we cut “Hey Jude”?’ I said, ‘That’s the most preposterous thing I ever heard. It’s insanity. We’re gonna cover the Beatles? That’s crazy!’ And Pickett said, ‘No, we’re not gonna do it.’ I said, ‘Their single’s gonna be Number 1. I mean, this is the biggest group in the world!’ And Duane said, ‘That’s exactly why we should do it — because [the Beatles single] will be Number 1 and they’re so big. The fact that we would cut the song with a black artist will get so much attention, it’ll be an automatic smash.’ That made all the sense in the world to me. So I said, ‘Well, okay. Let’s do it.’

It was because of great minds and talents combined with gritty determination to overcome the boundaries of class, race, and politics — even the Long-Haired hippy and southern rockers of the seventies like the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd who made their indelible mark and became popular at the shores of the Shoals — that makes the Muscle Shoals such an incredible entry in the real mythology of Americana. As enduring, unforgettable, and indestructible as any dream born of the American soul for anyone willing to chase it. Despite politicians and television grifters who would have us believe America is a hateful, racist, shameful country, experience and history tell a very different story. The story of people coming together for a common cause, to create great art, to enjoy and learn from each other and build another layer of complexity and inspire awe and challenge future generations to carry on this great legacy is what America is, was, and will be.

Sweet home Alabama

Where the skies are so blue

Sweet home Alabama

Lord I'm comin' home to you

Here I come, Alabama

Now Muscle Shoals has got the Swampers

And they've been known to pick a song or two

Lord they get me off so much

They pick me up when I'm feelin' blue

Now how about you?

—Lynyrd Skynyrd, “Sweet Home Alabama”

As always, I deeply appreciate your readership. Your time is extremely valuable, and try to make each post worthy of it. I welcome any comments on this or any post that strikes your interest. Thank you, Jenna.

An excellent essay. An excellent rendition of American music heros. I was reading along and was going to suggest one of my favorite songs the Wilson Pickett/Duane Allman collaboration and you included it. Duane Allman began playing guitar at 14 and he never stopped. Amazingly he had only been playing 8 -9 years when he worked with Pickett. Eric Clapton wrote in his autobiography Duane Allman was the "musical brother I'd never had but wished I did." His solo on "Layla" was haunting and beautiful. Dead at only 24!

Great piece. The success of Muscle Shoals reminds my of how User Generated Content, such as on Substack, has given opportunities to people whom the leftists gatekeepers would have denied a voice.

"Well I heard mister young sing about her

"Well, I heard ole Neil put her down

"Well, I hope Neil young will remember

"A southern man don't need him around anyhow."