“And because when you die, the world dies, too, at least for you, they assume the world will die for everybody. It’s a failure of imagination, in a way — an inability to conceive of the universe without you in it. That’s why old people get apocalyptic: they’re facing apocalypse, and that part, the private apocalypse, is real. So the closer their personal oblivion gets, the more certain geriatrics project impending doom on their surroundings. Also, there’s almost a spitefulness, sometimes. I swear, for some of these bilious Chicken Littles, imminent Armageddon isn’t a fear but a fantasy. Like they want the entire planet to implode into a giant black hole. Because if they can’t have their martinis on the porch anymore then nobody else should get to sip one, either.”

― Lionel Shriver, The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047.

Spring is when the foxes appear. There are usually seven or eight kits born to the mother who takes up residence under my neighbor’s shed. They seem to come earlier than I expect, emerging through the muddy gap as the frozen Minnesota ground gives way to emerging new life; the long shadows of winter shaken off as the blue sky winks away the gray. But the fox family is rebirth, even before the first green shoots of crocus leaves or buds of the magnolia and plums. The playful creatures wrestle with each other, harmlessly pawing and tumbling amongst the dried leaves leftover from the previous fall, all under the watchful, wary eyes of their mother.

In the street, the passersby pause and watch. The joyful carefree creatures are nature’s spring gift to us who spend the winter season in a state of semi-isolation: separated by the hurried trips from shelter to shelter, scarved faces, oversized coats and parkas that do as much to hide us from each other us as the frigid weather. The neighborhood kids in their oversized galoshes, dragging sticks along the sidewalk, whose attention is held as briefly as the shallow puddles hold water will sit, captivated.

But one day this year, as my husband and I were passing the makeshift den, pushing our own baby in his stroller, one of the kits was motionless on the ground, not more than a foot from the shed. Its tiny body contorted in a way that we had a full view of its face. Our slowed gait caught up with the realization the kit was dead. Its lifeless, pathetic body alone in the stale grass, abandoned by his siblings.

There was something about this poor creature, with no signs of distress or wounds, with no apparent cause of death that left me with a hollow feeling. It was helplessness mixed with sadness that caused me to search my mind for some rational cause. Maybe because I was a new mother that I felt remorse at this loss, an animal that owed nothing to man, and man owed nothing to it — yet it haunted me. Every person that passed had the same reaction: slowing to see this baby lying out in the open, then looking away with a quickened pace; mothers pulling the small hands of their children away and out of view of the kit, hoping to outpace the sadness. Out of sight, out of mind.

My reaction was childish: I just wanted to do something. But there was nothing to be done. And that was perhaps the source of my unease.

The horror of the murder of children in Uvalde was more than a tragedy. It is the sort of unimaginable event that reminds us of the depths of sorrow and pain a human heart can bear. And as more details became known — the terror those children must have experienced; the desperation of those parents forced to sit as witnesses to the evil happening inside the school where their babies were trapped; the gross inaction of law enforcement; the background of the young man and his family as a horror hiding in plain sight — our sorrow and grief turned to anger. Do something, the cries now ring out as a collective cadence to a march for action.

But what exactly, does that mean? Whether the words are screamed in frustrated anguish or whispered in quiet despair, shouldn’t there be a clear idea of what problem needs to be confronted, of what that something is supposed to fix? Or is it just an unavailing exercise in self-soothing that we join a chorus that speaks the words without intention the intention of action — like children’s empty threats in a schoolyard skirmish?

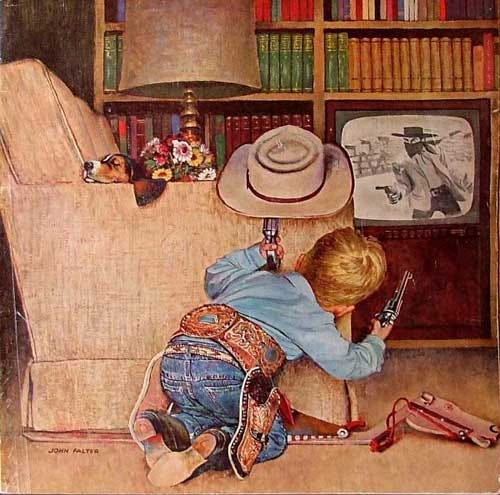

“Do something” is a visceral reaction. It is a phrase that offers no tangible solutions and lacks any means of measure toward success. Uttering it reveals a shallowness of thought and purpose. We are in a crisis of willful ignorance about our own superficial nature, and it perpetuates a childishness without innocence that dooms us to our present reality. Absent immediate danger, “do something” is an assuagement of anger, a palliative for the guilty conscience for those who are not interested in finding hard answers to difficult questions.

Giving in to the childish impulse to “make it better,” is simply a workaround. It is recreating a problem so we can place it in a neat box tied with a tidy bow; a superficial response to match our inadequacy in solving it. We want to keep our feeling of innocence as much as, or even more than, protect the innocence of the victim, even though it has become an impossibility.

But innocence has long since passed for adults living in a dangerous world and pretending one can hold on to it is a vulgarity to decency and integrity and honesty. It is sacrificing truth in order to keep believing a lie — and it is done with eyes wide open. It is what must be done to live with ourselves, and the guilt, and to look away from the tragedy of dead virtue. Joan Didion wrote in her 1979 work The White Album, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

It is true the socio-political environment has made it difficult to separate the narrative from reality. A media blob complicit with the politically powerful perpetuates the elevation of cowards who at once infantilize their audience and bow to the pressures of a radical mob. It creates a vacuous hole of responsibility and Americans who accept this situation with apathy are as appalling as the institutions we have allowed to rot before our eyes.

In the preface to her 1968 collection of essays Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Didion wrote

Slouching Towards Bethlehem is also the title of one piece in the book, and that piece, which derived from some time spent in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, was for me both the most imperative of all the pieces to write and the only one that made me despondent after it was printed. It was the first time I had dealt directly and flatly with the evidence of atomization, the proof that things fall apart … that the world as I had understood it no longer existed.

How long can we place the blame solely on politicians and leaders to whom we gave power? At what point do we decide we cannot continue down the path of self-deception? How much of our freedom are we willing to trade so we can hide like little children under the skirt of an overbearing government that has neither maternal wisdom nor the unprejudiced discipline of a loving mother?

G.K. Chesterton wrote an essay in response to a letter printed in The Daily News on August 16, 1905 entitled “What’s Wrong With the World?” It has often been misconstrued, but according to Julia Stapleton’s text, “Chesterton at the Daily News: literature, liberalism and revolution, 1901-1913, volume 3, January 1905 to June 1906,” Chesterton wrote, “The answer to the question, ‘What is Wrong?’ is, or should be, ‘I am wrong.’ Until a man can give that answer his idealism is only a hobby.”

The heavy hand of tyranny looms large; it is a menacing fist clothed in velvet compassion. For the common good! is the loyal subject’s answer to Do something! They are words without meaning because they are spoken without purpose — present on the lips but not in the soul. They are only valuable to those who demand obedience, but it is we who utter them anyway. From disavowing Western tradition, rejecting objective truth, and allowing our history to be rewritten, to absolute acceptance of dogmatic moral superiority, words are violence, and sex as a social construct, we allowed the destruction of society brick-by-brick, believing each one is ground into dust would be too small to collapse the whole structure. But we had it backward: each brick depends on all the others to form a strong foundation.

We have created a malady-stricken society. We are unwell but we accept living merely at the tolerance level of our pain, apathetic to the idea that life could be so much more. We cannot allow ourselves to be lied to like little children, then claim feigned indignation when those lies don’t protect us.

We can either act like children or protect them, we cannot do both.

Following events like Uvalde, Americans enter an unrequited search for answers when there seems to be none and we are faced with a choice: pursue a solution to a problem with full knowledge that it might lead to unexpected places, or answers much different from those predetermined by unthinking politicians and self-appointed experts; or to live with our self-created misery and resigned apathy, covering for our avoidance of responsibility with our good intentions. We have self-selected a predetermined conclusion by the process of elimination. It is bigoted to talk about our disgraceful public school system; it is offensive to criticize inadequate mental health care; it is hateful to reassess the heavy toll on society in the wake of broken families, drug abuse, and crime. To do something, in this case, is to confront our propensity to hide beneath the blanket of false innocence. Because we are not innocent when we refuse to accept our adult responsibility. No matter how many times or with any degree of intensity and passion we utter “do something.” It is in vain.

I contrast this time with a moment to which I return frequently: September 11, 2001, and a man on United Airlines Flight 93 headed to California from Newark International Airport. Thomas Burnett, Jr. grew up in my hometown, we graduated from the same high school, and he attended the Catholic church not far from my present home. In the courtyard of the garden of that church lies a brick bearing his name. On it is the simple description: “Our Hero.”

Burnett’s final phone call on that infamous day — from that plane to his wife, Deena — is what Do something really means. I urge you to read it in its entirety here.

6:54 a.m. Fourth cell phone call

Deena: Tom?

Tom: Hi. Anything new?

Deena: No

Tom: Where are the kids?

Deena: They’re fine. They’re sitting at the table having breakfast. They’re asking to talk to you.

Tom: Tell them I’ll talk to them later

Deena: I called your parents. They know your plane has been hijacked.

Tom: Oh…you shouldn’t have worried them. How are they doing?

Deena: They’re O.K.. Mary and Martha are with them.

Tom: Good. (a long quiet pause) We’re waiting until we’re over a rural area. We’re going to take back the airplane.

Deena: No! Sit down, be still, be quiet, and don’t draw attention to yourself! (The exact words taught to me by Delta Airlines Flight Attendant Training).

Tom: Deena! If they’re going to crash this plane into the ground, we’re going to have do something!

Deena: What about the authorities?

Tom: We can’t wait for the authorities. I don’t know what they could do anyway.

It’s up to us. I think we can do it.

Deena: What do you want me to do?

Tom: Pray, Deena, just pray.

Deena: (after a long pause) I love you.

Tom: Don’t worry, we’re going to do something.

He hung up

Thank you for reading this post. I try to be thoughtful and honest with my writing — a way to express my gratitude for your valuable time. If you have comments or insight you would like to share, I encourage you to do so.

The question is always looming in my mind. What happened? Where did our men and women of honor and courage go? It may be safe to imagine the last of our truly good men were on flight 93. But I think that's a stretch.

A friend and I took a trip to DC as tourists. I convinced her to take a road trip to Shanksville, PA. Reluctantly she agreed. My friend thought it would be a hole in the ground with a memorial.

The drive was beautiful, and the traffic was unexpectedly heavier than I had thought. There were a lot of Harley bikers trekking to the same hole in the ground as us.

My curiosity was piqued, and she was undoubtedly surprised. We arrived and to describe the magnitude of what we saw renders one speechless. Quiet, emotional respect. I was fighting back one of those ugly cries someone would have caught on video and posted it.

The Flight 93 memorial is something every young person should see. Maybe they would see our heroes are not always dressed in military fatigues and lugging big guns.

The young men and women might see the hero in themselves and decide our country is worth fighting for, on and off the battlefield. That's what one would hope. I do.

Beautiful article you wrote, Jenna.

"We can either act like children or protect them, we cannot do both."