The Epiphany of Beauty

Creating art that frees us to a transformation toward the true and the good.

Do you remember seeing the most beautiful thing in your life? If you close your eyes, can you see it and perfectly recall how it made you feel — every detail hums together like the rhythm of breathing. It’s the turn of a knot in your heart. It stirs the thing in you that wasn’t there just moments before, as if the dawn illuminated your soul for the first time. And you’re free.

The epiphany is not just for screenplays and character arcs. It’s the first petal of a flower breaking open allowing the rest to follow. It’s throwing open the windows of a shuttered room to let in the light and release the suffocating staleness of lifeless malaise: Here is the beauty waiting for us to catch it like a wild horse and lead us on paths not yet tread. Epiphany as a change of being. A revelation. It is the chains of despair breaking away and revealing a widening horizon out into an expansive sea of moral clarity, purpose, and love.

It seems easy, doesn’t it? Tossing our insecurities and doubt and closely held golden-spun narratives that we’ve used as comfort blankets and shields and go without a bridle into a dangerous, hungry world. But letting go of habits and mindsets we know are causing our self-destruction is the hardest. Flannery O’Connor writes in The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O'Connor, “All human nature vigorously resists grace because grace changes us and the change is painful.” Read O’Connor’s A Good Man Is Hard To Find for how painful this could be. “‘No pleasure but meanness,’ he said and his voice had become almost a snarl.”

But is there another moment of epiphany that is as transformative and revelatory and as accessible to us not like a bullet but in the radiance of a painting or the harmony in the lines of a great book?

I recently went on a work retreat that happened to still be work and not a retreat so much as an advance forward on behalf of the good. But it was a “retreat” out of our office into a private residence for the day. The home is lovely and warm and full of the things that mark time well lived. The house is lovely; the lady of the house is beautiful — striking really. But it shouldn’t be surprising that the people who occupy a house full of beautiful things — not merely the temporarily satisfying but things with deep value — will radiate the same beauty.

Noticeable in this home was the abundance of books and art. Precious things that weren’t hidden behind doors or in cupboards. Even the collection of well-loved cookbooks (favorites of mine as humble time capsules from far-gone Americana) occupied a prominent place in the sun-spilled kitchen.

Being surrounded by beautiful things, positioning oneself before the gateway to the True and Good as the transcendental tradition would have it, isn’t parceled off for the well-heeled or cultured. I remember my grandparent’s lakeside home — a converted cabin in rural Minnesota — where I had my first impressions of art that would endear itself into adulthood. Two of Winslow Homer’s pastoral scenes were represented in small prints hanging in the wood-paneled, unassuming guest room that doubled as my grandfather’s study. “Snap the Whip” (1872) and “The Veteran in a New Field” (1865) were beside the taxidermy walleye above the hulking rolltop desk. The other bedroom had a print of Andrew Wyeth’s “Master Bedroom,” a 1965 watercolor that could have been the model for the room where this print was placed.

Beauty is not something to be seen but allows us to see. Beauty Integritas or wholeness, Consonantia or harmony, and Claritas or radiance and clarity — what Aquinas calls the three conditions of beauty in his Summa Theologica.

Beauty is unfairly an afterthought, a tertiary component in a world that lives and dies by bitter fights over the others, forgetting that it was beauty that launched a thousand ships. But truly deep, resounding, radiant beauty is overlooked in a culture obsessed with appearances.

The Swiss theologian and Catholic priest Hans Urs von Balthasar (12 August 1905 – 26 June 1988) wrote in Seeing the Form (1961),

We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance. We can be sure that whoever sneers at her name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past -- whether he admits it or not -- can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love.

When you’re with someone who radiates beauty, stand in the presence of a beautiful work of art, hear it in music, or read a beautiful sentence or line of poetry, it urges you on to more — it draws you in. You want to be nearer.

Beauty begets its pursuit. Begin to search for it, and everywhere it appears and acts as the alchemy of the soul, transforming mind and imagination away from the depraved, the jealous, spiteful, and resentful. It has the unique power to instantly remind us of our humanity. And here is where the task of the artist — the creator of beauty — has a role so important that I would argue it is vital to understanding the human condition.

Walker Percy writes in The Moviegoer, “The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.” To receive true beauty is shocking — and has the power — much like grace — to shake us from our despair and lead us to search for the source of beauty.

“Boredom is the conviction that you can't change ... the shriek of unused capacities” writes Saul Bellow in one of the great American novels, The Adventures of Augie March. At its core, it is one boy’s journey through the streets of pre-WWII Chicago searching for love. It is understood at the outset how high are the stakes when Augie must leave his disabled brother Georgie at an institution. The pain is tangible. Bellow writes, “Death is going to take the boundaries away from us, that we should no more be persons. That's what death is about. When that is what life also wants to be about, how can you feel except rebellious?”

Rebel against an ugly world. Rebel against the subjectively satisfying, empty-calorie sugar high of temporary satisfaction. Rebel against the malaise. Rebel against settling for as good as it gets. Rebel against boredom and safety. Pursue beauty. Risk discomfort. Risk the being shocked out of your despair and open yourself to the possibility of grace and beauty and truth and goodness. There will be suffering, but there will be life; and life beyond.

Art and the artist offer a pathway to rehumanizing ourselves and our culture instead of inspiring resentment or being merely satisfied by having our prior assumptions validated.

It is hard to see the beauty behind the suffering. But we can see grace at work. The shock of it is just as much beauty as it is suffering. It is meant to stop us in our tracks. It is meant to urge us to search for what lies behind the beauty: wholeness, harmony, and radiance. The hidden beauty and the fount from which it flows. Drinking from it quenches our thirst for Truth and the Good. And how do we see it? Through the lines of the poem, the harmony of a song, the one true sentence that Hemingway pursued. It is both a gift and a necessity, as poet Mary Oliver declares in her Poetry Handbook, “Poetry is a life-cherishing force. For poems are not words, after all, but fires for the cold, ropes let down to the lost, something as necessary as bread in the pockets of the hungry.” The beauty of a poem is as the beauty of art. Art is the essence of beauty. When we dismiss art — literature, art, music, poetry — we cut off our humanity and the ability to be open to our spiritual thirst, our openness to understand our time, and where we as individuals and communities are woven within it.

In 1965, Pope Paul VI addressed artists in a letter at the closing of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council,

This world in which we live needs beauty in order not to sink into despair. It is beauty, like truth, which brings joy to the heart of man and is that precious fruit which resists the wear and tear of time, which unites generations and makes them share things in admiration. And all of this is through your hands. May these hands be pure and disinterested. Remember that you are the guardians of beauty in the world.

[I’m not Catholic. I include the Pope’s letter because someone with his influence and power specifically addressing this topic is more than noteworthy and suggests the importance of artists in creating beauty and its inextricable role in connecting people and society to their humanity]

In her 1958 memoir, Hollywood journalist Sheilah Graham recalls a memory from F. Scott Fitzgerald, with whom she had an affair toward the end of his life, “That is part of the beauty of all literature. You discover that your longings are universal longings, that you're not lonely and isolated from anyone. You belong.” Fitzgerald found out Graham lacked formal education and became her tutor, reading poetry, literature, and great texts. [The relationship was made into a Hollywood film starring Gregory Peck, Deborah Kerr, and Eddie Albert: 1959’s “Beloved Infidel.”]

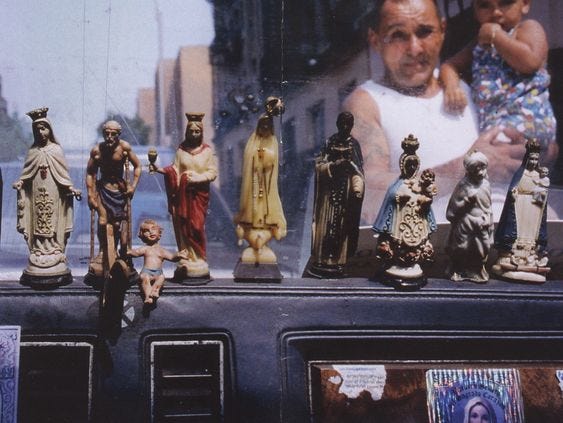

James Joyce modified epiphany from a religious expression, writing in Stephen Hero that epiphany is “a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether in the vulgarity of speech or of gesture or in a memorable phase of the mind itself,” and “the soul of the commonest object… seems to us radiant, and may be manifested through any chance, word, or gesture.”

Beauty, like grace, seeks us, and we need only to meet it and accept it and the suffering that goes with such a transformation. But the artist, the creator, can help connect us to it and our humanity, which ultimately leads us to the true and good.

Recalling the 1965 address, Pope John Paul II wrote his own letter to artists in 1999. He writes of the importance of art and beauty to the world and the soul and the eternal search, writing,

Every genuine artistic intuition goes beyond what the senses perceive and, reaching beneath reality's surface, strives to interpret its hidden mystery. The intuition itself springs from the depths of the human soul, where the desire to give meaning to one's own life is joined by the fleeting vision of beauty and of the mysterious unity of things. All artists experience the unbridgeable gap which lies between the work of their hands, however successful it may be, and the dazzling perfection of the beauty glimpsed in the ardour of the creative moment: what they manage to express in their painting, their sculpting, their creating is no more than a glimmer of the splendour which flared for a moment before the eyes of their spirit.

And

Every genuine art form in its own way is a path to the inmost reality of man and of the world. It is therefore a wholly valid approach to the realm of faith, which gives human experience its ultimate meaning. That is why the Gospel fullness of truth was bound from the beginning to stir the interest of artists, who by their very nature are alert to every “epiphany” of the inner beauty of things.

The letter ends with St. Augustine’s Confessions,

Beauty is a key to the mystery and a call to transcendence. It is an invitation to savour life and to dream of the future. That is why the beauty of created things can never fully satisfy. It stirs that hidden nostalgia for God which a lover of beauty like Saint Augustine could express in incomparable terms: ‘Late have I loved you, beauty so old and so new: late have I loved you!’

Artists of the world, may your many different paths all lead to that infinite Ocean of beauty where wonder becomes awe, exhilaration, unspeakable joy.

What does the house we built for ourselves reflect — the echoing walls of emptiness and unfulfilling entertainment or ignorance or temporary comforts, or the welcoming warmth of beauty, the pain of transfiguration in pursuit of truth and the good, and the suffering of grace?

When we destroy icons, when we turn from beauty in favor of identity quotas, or to prop up a lie, we strip our souls of humanity and deny the art and literature that opens us to the wide horizon of earthly and ethereal possibility. I hope this (long!) meandering post helped express that. Thank you for following along. Please leave a comment or critique if you’re willing.

Sincerely, Jenna

This is for my mom, who is more than I deserve and set the highest bar for teaching me about beauty, grace, the truth (always), and goodness in heart and spirit, even when I doubt its existence. Thank you.

Jenna,

It is always a wonderful surprise when one of your essays appears in my inbox. With great anticipation I put everything else on hold to see what imaginative journey you have written for us. You never disappoint. It is my personal quirkiness to start reading and quickly pick out a particularly phrase or sentence early in the journey that appeals to me. My mind wonders — “that is so profound” — how can I include that gem in a well deserved comment? Fortunately, I usually snap out of it and continue reading…

This is one of your finest works. I loved it on so many levels. I can only imagine the time, effort and research you expended. I wish I were able to properly express my admiration for your writing abilities. You tell beautiful stories that are works of art.

A “Thank you” seems inadequate.

Wonderful post... there's so much ugliness in the world today that it makes seeing beauty so important now!