I could start at the end of John Ford’s epic film The Searchers. John Wayne, dark and back turned to the camera, silhouetted against the frame of a house. Before him is the vast backdrop of the American frontier.

It is an awe-inspiring scene. Wayne heads out into the open range; I’m left in stunned silence at his larger-than-life figure and a wrenching feeling of defeat shown by this man achieving his ultimate goal and by the prospect of heading out with an uncertain future and no sure path to a settled heart and mind. The first time I saw it, I was left with more questions than answers — and the answers were somewhere out there.

Ford’s genius was his ability to touch people in a visceral way just through sweeping cinematography. But what Ford delivered through the screen wasn’t propriety. He simply brought was out there for anyone to discover in the dark seats of a theater and let people’s imaginations do the rest.

But the little secret I held in my heart was that I had been out there. It was America, and it was — even 131 years after Alexis de Tocqueville’s sojourn across the country still is — waiting to be discovered, and the best way to do it was to through the open road.

Summertime means vacations for many Americans, and especially after years of lockdowns punctuated by the present economic uncertainty, people are anxious to escape from the ordinary. For many, this involves jetting off to Europe or that Mouse House theme park to be steeped in artificial smiles and long lines. But I want to share my secret: pack up the car and drive. See America. Experience the magic that Ford tried to emulate on the big screen but that was ultimately too small to capture: the majesty, the romance, the grit, and wind-whipped expanse that raised and formed generations of Americans — all on their own journey, in pursuit, searching, for the American Dream.

My family spent a lot of time on the road courtesy of poor means, big plans, and a pink-striped GMC conversion van. It was the best gift my parents could’ve given me and my brothers.

What I saw and learned traveling the country from North Platte, Nebraska, to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, is that this is America just as much as New York City, Los Angeles, or Washington, DC. I learned more about what it was to be an American and live in America on those trips than in any college lecture hall or pages of the New York Times or The Wall Street Journal. This was Mainstreet — U.S. Route 66 to put a finger on it. It was the Great Diagonal Way; “The Mother Road” as John Steinbeck called it in his 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath. It started in Chicago. The rolling 9-foot-wide single lane, 2,448-mile road wove itself into the landscape, reaching like an outstretched arm pointing the way to California. Santa Monica was where the road terminated, but it didn’t end the idyllic vision of millions of travelers who chased the sunset before they were forgotten beneath the night’s dark shroud. For Steinbeck, Route 66 more represented desperation than hope, more abandonment than rebuilding. He writes “How can we live without our lives? How will we know it’s us without our past?”

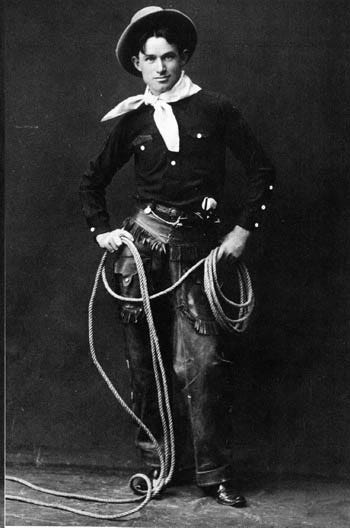

But where Steinbeck eulogized the America of his Depression-era works, the period’s American Everyman personified hope and optimism. Will Rogers was that American archetype. Born in Oklahoma into the Cherokee Nation on his parent’s Dog Iron ranch, he understood the frontier. He experienced the oppressive poverty too prevalent in his Native community, but arguably most importantly, he believed America was an open road, leading to a life that was ultimately up to him. He became a vaudevillian, a radio star, actor, humorist, and commentator. By the early 1930s, he became one of the most popular actors in America. Unsurprisingly, his favorite director was John Ford, with whom he made three of the over seventy films in his career, Doctor Bull (1933), Judge Priest (1934), and Steamboat Round the Bend (1935). The pairing was a showcase of Americana: Rogers’ widespread appeal and representation of the self-deprecating common man and Ford’s gift of transfiguring American idealism into the passions and soul of the individual moviegoer. A political Democrat who was never defined by party labels, he befriended both presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge. He was at once Bob Hope, Andy Rooney, and Buffalo Bill Cody.

Now, politics has driven a wedge between the seen and unseen in America. One end is a political class that uses pedigree as a self-anointing hierarchy of rule-makers. Academics spend their lives writing case studies on socioeconomic inequality but never bother to live or talk to people experiencing poverty at the hand of years of trade inequality. Americans haven’t changed all that much, but the views and dominating elitism of those who think they have a claim to their dreams have. Basket of Deplorables; Back Row Americans; Hillbilly Elegy. Politicians assured us cheap manufacturing in China was worth the sacrifice of American jobs in Pennsylvania or Ohio or Michigan. Modernists scoffed at traditional religion as an agent of oppression and sexism. Feminists raged at the patriarchy, ushering in a false promise of women’s “liberation” from the burdens of family.

We are tired of the overbearing hubris of the well-heeled making claims of settled social science about the rest of us. The backroads of America tell the story of courage, sacrifice, grace, and compassion just as any high rise in New York or conference table in Washington. What is missing is Will Rogers.

The great American road trip isn’t just about the historical landmarks and the battlefields and the national parks, I learned about who and what is in between. The truckers crisscrossing the interstates are the pipeline bringing us the food, goods, and livestock this country needs to sustain itself. There were families like ours out to explore the wide-open roads. We ran into modern-day Okies, their lives packed up in a truck headed for the hope of a better life in a new homestead. The occasional hitchhiker, head resting on his backpack, taking a nap in the shade of the overpass. There are little towns and cities scattered off the beaten path, just the blink of any eye when traveling by train, completely missed from the windows of an airplane.

Right now, there is a divide between those shuttling along the Acela Corridor and the rest of the country. At best they ignore “flyover” Americans, at worst they’re considered philistines — one factory closure away from extinction. But the greatness of America defies that mentality. It isn’t political. It’s the desire for each of us to strive for a piece of the American Dream — American Possibility. And that looks different in New York City, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Amarillo, or Winona. It’s the idea that each of us can pursue that which makes us happy and fulfilled.

Tocqueville wasn’t the only great mind who toured America to find its essence. G.K. Chesterton did it during Rogers’ rise to fame, first on a lecture tour in 1921, then later in 1930-31 while he was at the University of Notre Dame. He wrote of his experience in two books, What I Saw in America (1922) and Sidelights on New London and Newer York (1932). In America, he writes

America is the only nation in the world that is founded on a creed. That creed is set forth with dogmatic and even theological lucidity in the Declaration of Independence; perhaps the only piece of practical politics that is also theoretical politics and also great literature. It enunciates that all men are equal in their claim to justice, that governments exist to give them that justice, and that their authority is for that reason just. It certainly does condemn anarchism, and it does also by inference condemn atheism, since it clearly names the Creator as the ultimate authority from whom these equal rights are derived. Nobody expects a modern political system to proceed logically in the application of such dogmas, and in the matter of God and Government it is naturally God whose claim is taken more lightly. The point is that there is a creed, if not about divine, at least about human things.

And

The Americans are very patriotic, and wish to make their new citizens patriotic Americans. But it is the idea of making a new nation literally out of any old nation that comes along. In a word, what is unique is not America but what is called Americanisation … America is the only place in the world where this process, healthy or unhealthy, possible or impossible, is going on. And the process, as I have pointed out, is not internationalization. It would be truer to say it is the nationalization of the internationalized. It is making a home out of vagabonds and a nation out of exiles.

It takes all sorts of Americans to be a successful nation. We find ingenuity, creativity, and productivity in our diversity, but only through a common belief that America is the last best hope for mankind will we succeed in this experiment of human nature. In the end, we’re all just trying to get from point A to point B. We can get there by different paths, but the goal must be the same. Right now, many Americans are feeling like refugees from a nation we no longer recognize as our own — a nation war-torn upon itself — and we are the ones “yearning to be free.” That freedom, that sweet air of opportunity, liberty, and unlimited possibility that was seemingly months before waiting for us just beyond the horizon appears to have vanished like a desert mirage.

Worse, average people were scolded for even pursuing it. Politicians told us of a liberal world order; they told us tales of transitory inflation and necessary gas price pain (that was the point). Journalists mocked the suffering families who had trouble affording milk or (like me) found bare shelves where there used to be baby formula. Will Rogers became an icon because Americans saw a piece of themselves in him. He traveled the nation to tell their stories (and died doing it), not to mock. He skewered politicians and elites while never forgetting his humble beginnings. He even ran a mock campaign for president on an “Anti-Bunk” platform (a kind of precursor to William F. Buckley, Jr.’s New York City mayoral run in 1965).

“The difference between death and taxes is death doesn’t get worse every time Congress meets,” “Be thankful we're not getting all the government we're actually paying for,” and “I don't make jokes. I just watch the government and report the facts” are a few quotes for which he’s famous. But through his show business career, his time on the Frontier and as a trick roper, and his columns for The Saturday Evening Post and the New York Times, he endeared himself to Americans of every background. His spirit lives on in the Will Rogers Range Riders of Amarillo, Texas — a city along Route 66. The Riders still hold a popular July 4th rodeo each year.

We have a choice of which road we follow: the road to depression, where hopelessness casts its long shadow under ominous clouds, where our passions are cooled and where once we saw possibility, we now see unattainableness, and the road to American Possibility is littered with dashed hopes and broken dreams.

Or we can refuse to let our lives be dictated by those whose only desire is control; who despise today’s Will Rogers, the common man, the adventurer, the independent mind, the seeker, and the man who follows his own path because he knows no other way to live. There is a reason why the historic Route 66 is nicknamed the Will Rogers Highway: it embodies the line that flows through the heart of every patriotic American — that there is a place here for everyone, and a road to get there.

As always, I’m very grateful for your readership. Time is one of the most valuable things we have and I try my best not to waste yours. I appreciate your interest and encourage feedback if so inclined. And if it strikes you, please share this post and A Pilgrim’s Progress. I hope you find a little bit of your journey in mine.

Great essay! I always look forward to your thoughts and insights into America and what she means to most of us. This essay takes me back to the words of Benjamin Franklin after crafting the Constitution to an anxious Mrs. Powell waiting outside Independence Hall “Do we have a monarchy or a republic”? Franklin answered, “A Republic, if you can keep it.”🇺🇸