On July 2, 1982, 33-year-old Larry Walters launched himself into the expansive, clear-blue sky over San Pedro, California — and into history. He was fulfilling a childhood dream — a vision, really. Defying everyone who told him it couldn’t be done; ignoring the rules that it shouldn’t be done. But he did it anyway. For Walters, his flying adventure was a deep desire that lifted his spirit somewhere over the green treetops and tiled roofs, out over the San Gabriel Mountains and the dry Mojave Desert.

According to published accounts, Walters was transfixed by the idea of flying, but not one involving traditional modes of flight. In that sense, he was a dreamer, a visionary, a nonconformist with a singular mission. From George Plimpton’s moving essay, published after Walter’s death in the June 1, 1998 issue of The New Yorker

[Walters] was spotted by Delta and T.W.A. pilots taking off from Los Angeles Airport. One of them was reported to have radioed to the traffic controllers, “This is T.W.A. 231, level at sixteen thousand feet. We have a man in a chair attached to balloons in our ten-o’clock position, range five miles.” Subsequently, I read that Walters had been fined fifteen hundred dollars by the Federal Aviation Administration for flying an “unairworthy machine.”

The “unairworthy machine” was a Sears-Roebuck lawn chair attached to 42 helium-filled weather balloons.

Walters’ vision was a personal one, but it isn’t singular in its relation to the American Dream itself: the untapped potential of thousands of dreams, unlimited in potential only by the restraints of imagination and fortitude. In the end, he was Icarus; but would it have been better to leave a dream unfulfilled — to live haunted by the despondency of unrealized meaning?

Wouldn’t you want the opportunity to find out?

***

“I am an American, Chicago born — Chicago, that somber city — and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent. But a man's character is his fate, says Heraclitus, and in the end there isn't any way to disguise the nature of the knocks by acoustical work on the door or gloving the knuckles.”

-Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March

America went from the mid-century’s optimism and opportunity traipsing on the heels of a Great Depression and a Great War, itself rhyming with the previous era marked by a generation lost to the ravages of the first world war contrasted to the lost inhibitions of the 1920s. Going back to the days of the frontier, and before that the birth pains of the Founding itself the divisions among people have been a vague menace. But it wasn’t enough to overcome naive eagerness and self-confidence.

In his book, The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism, author Yuval Levin explains how America’s outlook is a reflection of the time when the prevailing (or in the case of our octogenarian Baby Boomers — ruling) generation came of age. In our stylized retro inspiration of that Golden Era we were gifted unbound imaginations and abundance: Jetplanes! Space Travel! New-fangled, plastic, pre-fab wares! Linoleum! Rock ‘n Roll!!

When President John F. Kennedy addressed a crowd of 40,000 at Rice University in the fall of 1962 expounding plans for America’s space program, he gave a speech of optimism tempered with the weight of great responsibility; a forward trajectory rooted in knowledge and realized through imagination:

Those who came before us made certain that this country rode the first waves of the industrial revolutions, the first waves of modern invention, and the first wave of nuclear power, and this generation does not intend to founder in the backwash of the coming age of space. We mean to be a part of it - we mean to lead it. For the eyes of the world now look into space, to the moon and to the planets beyond, and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace …

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

Kennedy himself was a child when Charles Lindberg embarked on his 1927 trans-Atlantic flight. When he was a young man who returned from war the nation was immersed in the science-fiction pop culture of the Buck Rogers archetype, the genre that found life outside of the shadows of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.

How then, did we go from Kennedy’s soaring rhetoric and its symbolic idealism to a dour, unfunny, country of scolds? How did a nation so ripe with innovation, so eager for new enterprises, fall into a malaise of desperate frustration, fear, and conformity rooted in bitterness?

Because we have been conditioned to believe that ideas are dangerous, and are an existential threat to our democracy.

The path to obsolescence is found in the refusal to explore ideas within the guardrails of morality. Change and growth — human progress — come from foundational confidence in a bedrock of principles that allows debate about changing conditions and makes those principles stronger. One can jump farther off a well-anchored platform than an unstable one. Menand wrote a New Yorker essay about the free speech radicals of the 1960s. “The Making of the New Left” details the path of prominent university students as they attempted to remake American universities into vehicles for social justice. “The students involved had experienced a feeling of personal liberation through group solidarity, a largely illusory but genuinely moving sense that the world was turning under their marching feet. That sense — the sense that your words and actions matter, that you matter — is what inspires people to take risks, and gives movements for change their momentum.”

But the seething protestors got caught in their own momentum and were ultimately run over by their own groupthink. The leftists who came of age in the late 1960s now look back breathing the rarified air of romanticism and revisionism. They see their activism as one of expansion even as their takeovers tenured their radical ideas and locked out dissenting ones. They came of age heroes of their own quixotic tale fighting The Man — and they became him. And now as we find ourselves on the cusp of incredible technological advances, embarrassing riches of information, of the unprecedented ability to share ideas across the globe, they want to stop it. They want to stop it because allowing it threatens their grip on power. They want to control it to protect the house of cards they built. They are increasingly intolerant of dissent even as they hold themselves as champions of tolerance. They embrace the contrarian only if he agrees with their narrative. No exceptions are allowed. Not even for Bob Dylan.

By 1964, Dylan was the folk prince of the protest movement; a mystic bard whose skyrocket to fame was hitched to his songs “The Times They Are a-Changin,” “Chimes of Freedom,” and “Masters of War.” But even as the folk scene lionized Dylan, christening him as its savior, the elusive artist was in the midst of a transformation — one that would cause his legions of devoted fans to turn against him. Dylan, with his acoustic guitar and harmonica, personified the political protests of the era. But instead of indulging his fans by churning-out self-aggrandizing mimeographs, he defied them.

Dylan’s nonconformist persona was appropriated by the 1960s youth temper tantrum machine as a rally for hippie contrarians and anti-establishment agitators. They mistakenly assumed they had created him and therefore could destroy him. In a striking display of this arrogance, Irwin Silber, the avowed Marxist and editor of Sing Out! magazine published an open letter to Dylan in its November 1964 issue criticizing this “new” Dylan:

I think that the times there are a-changing. You seem to be in a different kind of bag now, Bob — and I'm worried about it … Your new songs seem to be all inner-directed now, innerprobing, self- conscious — maybe even a little maudlin or a little cruel on occasion. And it's happening on stage, too. You seem to be relating to a handful of cronies behind the scenes now — rather than to the rest of us out front.

Now, that's all okay — if that's the way you want it, Bob. But then you're a different Bob Dylan from the one we knew. The old one never wasted our precious time.

Eight months later Dylan would cause a cultural earthquake, not for his role in the ‘60s protest movement, but in his rejection of it. At the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Dylan went his own way and never looked back.

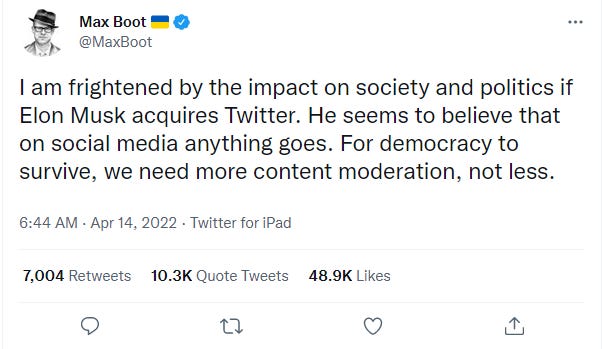

We see echoes of this as Elon Musk challenges the means of their control. Once heralded as an innovator of green energy and electric cars, Musk committed the ultimate sin by defying the first rule of the left: Obey All Orders. In outlandish displays of cowardice and cravenness, the left’s thought police went on the offense. The foot soldiers in the media readied their arrows and aimed directly at Musk:

Independent thought is not an option — it is much too dangerous.

It is this antihero, the heretic of the leftist religion, who refuses to be the face of the cause he never asked to join that they cannot stand. And he is hated for it. America needs to cultivate this spirit because it will not happen in China, Russia, or even in Australia or Canada. It is as much Bob Dylan and Elon Musk as it is Larry Walters or Bellows’ Augie March.

When asked if he thought of fulfilling his desire to fly by parachuting or flying a plane, Walters responded, “Absolutely not…no, no, no. It had to be something I put together myself.”

There is power in the nonconformist. It’s a freedom from being enslaved to those who want you forever chained to their institutions. Liberty is being able to question & defy those who crave your dependency. Deny them the pleasure.

Thank you for sticking with this (rather longish) post. Your time is precious and I hope to add value to this limited commodity. As always, I enjoy your feedback and encourage you to leave a comment. Exchanging ideas helps to sharpen the mind and focus the spirit.