Every day, people go about their business of business in the broad swaths of the land we share that is America. Going to sleep under the neon lights as dawn breaks in the concrete smoke-steaming cities or rising before the moon tucks itself back under the horizon to settle the livestock with morning rations or settle morning commuters behind galvanized metal counters of bakeries, sliding softly shaped dough bubbling and rolling in hot oil fryers. The faces of Americans waist deep in the everydayness of their lives, eyes in front of the horizon and dreaming beyond it.

It is something of sport now for people to look back in time with a cynic’s glare in disbelief of this thing we came to call a country rather than our country and that it belongs to the inhabitants of such wild imaginations and unbridled boldness that eventually tamed the world in its favor. Disdain would come with finger-pointing and scorn at traditions and mores that took generations to solidify but were instantly pummeled into ashy powder. The adventurer spirit, the restless pilgrim, the searcher, the cowboy, the swashbuckler, the defiant non-conformist rabble-rouser. These American glory myth characters persist beside the work-a-day waitress and barkeep, housewife and miner, teacher and typist. A study in contradictions that is the character and caricature of America from within and without its shores.

Intellectuals too beholden to their moral goodyness study and ponder the contradiction, and they decide on our behalf that one side must win in this intense political and cultural war waged by ideologues. Pointy-shoed bowtie boys harass us from teevee sets and endlessly scrolling screens, all tolling the bells for Everymen to join the battle for the soul of stoic and steadfast Lady Liberty.

Except, she is not asking to be saved. She is here to save us from ourselves and those who love personal power and influence more than service to country and her ideals. The people who shroud their avatars in the flag hide their loathing of the millions of faces that gaze out of car windows and storefronts and barn doors and suburban school buses. They hate that America is a perfect contradiction yet manage to head for a perfect union despite stormy seas and perilous side-to-side lists that would make the most seasoned sea captain churn his loins.

In modern times, one can look to a single point when the roads converged and diverged at once in a beautifully harmonious contradiction, as Fate’s light hand swept over the land and graced us with His glory. This terrible, formidable, profound responsibility offered freedom conditioned by duty. That terrible, formidable, profound decade is constantly heaped with halcyon nostalgia and insolent condescension and contempt — depending on what political tribe one swears an oath: the 1950s. 1955 to put a button on it. 1955! Oh, the pink bathroom-Formica-atomic eclectic 1955. A year of Technicolor and Kodachrome and a flash-blink of CinemaScope that burst out at movie house audiences in full, wonderous depth with a largeness that matched celebrity adoration.

Dipping a toe into that most mid of midcentury year, one might decide to rear back and take a running leap, plunging head-first into it. Despite what the long-faced, silky-handed academics and serious-minded social commentators who bang away at history like sour-mouthed headmasters rapping the knuckles of disobedient schoolchildren say: the era was one of oppressive conformity, ticky-tacky lives lived in ticky-tack homes with sprawling suburban lawns of shallow, white-bread families where no one was able to live his or her (or they/them/zhes) “authentic” self.

But it wasn’t the one-dimensional, chrome smile, Hawaiian shirt at the neighborhood tiki-party barbeque, either. The present has the advantage of looking back through time from modernity’s comfortable armchair. Review and revision are never attempted through a perfectly clear lens, but it’s often done through the lens of perfection. In this sense, America is seen as a nation of problems to be solved rather than a mystery to be explored. There is no country better suited for exploration, soul searching, discovering purpose, a driving force, or a backdrop for which we define ourselves — even as we defy definition. The American restlessness and coordinated contradictions are traced back to the original searcher, Alexis de Tocqueville, as he writes in Democracy in America:

At first sight there is something surprising in this strange unrest of so many happy men, restless in the midst of abundance. The spectacle itself is however as old as the world; the novelty is to see a whole people furnish an exemplification of it.

Their taste for physical gratifications must be regarded as the original source of that secret inquietude which the actions of the Americans betray, and of that inconstancy of which they afford fresh examples every day. He who has set his heart exclusively upon the pursuit of worldly welfare is always in a hurry, for he has but a limited time at his disposal to reach it, to grasp it, and to enjoy it.

The recollection of the brevity of life is a constant spur to him. Besides the good things which he possesses, he every instant fancies a thousand others which death will prevent him from trying if he does not try them soon. This thought fills him with anxiety, fear, and regret, and keeps his mind in ceaseless trepidation, which leads him perpetually to change his plans and his abode.

If in addition to the taste for physical well-being a social condition be superadded, in which the laws and customs make no condition permanent, here is a great additional stimulant to this restlessness of temper. Men will then be seen continually to change their track, for fear of missing the shortest cut to happiness.

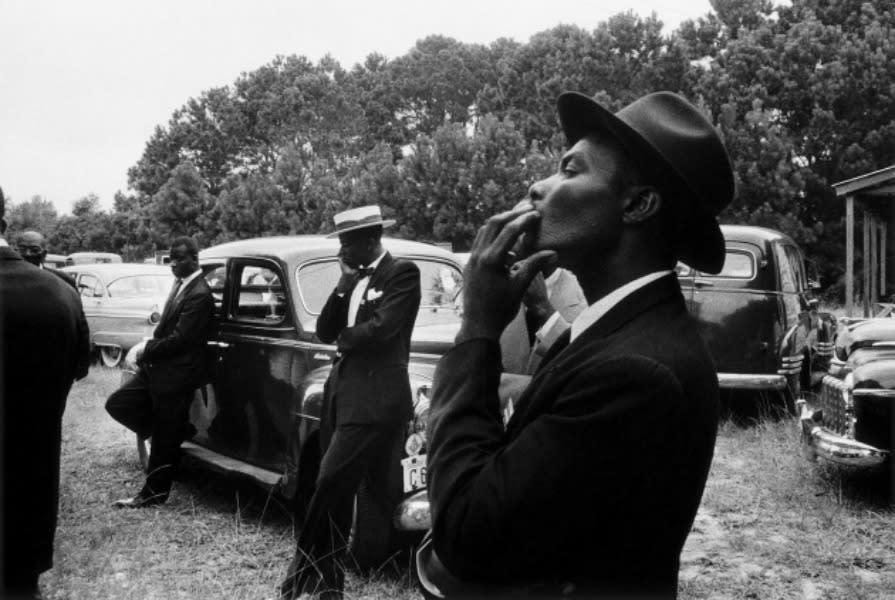

Tocqueville wasn’t the last man to search for the essence of America and the Americanness of people collectively settled but never settling. A mere 124 years later, in that magical year 1955, photographers Robert Frank and Todd Webb embarked on their journey of discovery to explore the mystery of America. They were unaware of each other’s aims before or during their project, made possible by separate Guggenheim grants. Webb — 49 years old, a Navy veteran, coming to photography later in life and an appreciation for the America hidden from view, such as his native Detroit — traveled by foot, boat, and bicycle, carefully and meticulously curating his scenes. Swiss-born Frank — a young 29-year-old, took to the road just a year before President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act; it was a precursor to the automobile age just on the horizon. Frank’s work was reflected in his piercing book The Americans — a collection of photographs from that cross-country trip. Webb’s photographs were lost to time and nefarious circumstances. It took 70 years to bring the two projects together with an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH).

Despite their differences in background, artistic style, and means of travel, they shared a vision: to search the in-between places for slivers of America to seep through the cracks of their preconceptions. Lisa Volpe, curator of photography at MFAH and author of the catalog America and Other Myths: Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955, writes about the exhibition and the two photographers’ undertaking, their expectations, and search for understanding:

Plunging themselves into these cross-country trips meant that both men were forced to grapple with the messy whole of the country, not just its individual aspects or its simplified ideologies. As they experienced America firsthand, they came to recognize the full scope of the social and cultural contradictions that defined life at midcentury.

What Frank and Webb discovered was more than what was reflected in the glossy pages of popular magazines, and it is often held up as the gold standard of The American Dream. Emblematic of this is the Museum of Modern Art’s lofty 1955 project “The Family of Man,” curated by the museum’s photography department director Edward Steichen, relying heavily on LIFE’s archival prints and Henry Luce’s other publications such as Time and Fortune. Frank and Webb had photographs in the exhibition, which toured America and, over several years, 37 countries worldwide.

In 1955 America, there was a sprint for the future and a lingering hold on the past. Two worlds that diverged but needed to coexist, even as the seeds of impending discontent of the 1960s and ‘70s were being planted. So, while “The Family of Man,” the photos in LIFE, and the Norman Rockwell covers of The Saturday Evening Post showed one side of America, it didn’t reflect every side (nor was that the goal — a valid editorial decision). Frank and Webb found unbridled consumerism, poverty, and racism in their travels. Despite a project that in some regard set out to contradict the polished images popular at the time, the different style of photography and aesthetics (Frank’s “shoot-from-the-hip” approach was a departure, feeling this was the strongest method to capture the essence of America while Webb’s camera work reflected the careful, slow, traditional method), generational difference in age, dissimilar background, and mode of travel, they couldn’t help but catch this persistent, stubborn American optimism.

It was hard not to in 1955. That singular year. America liked Ike, loved Lucy, and drove Sea-Mist Green Bel Airs. The suburbs were beginning to sprawl, and jazz rocked an urban beat. Disney World opened the doors to its magic kingdom to everyone willing to pay and Ray Crock started to feed them hamburgers. Kids had coon skin hat fever dreams and sang “The Ballad of Davy Crockett.” 1955 saw movie star John Wayne make his television debut on Gunsmoke, the year that legendary show aired its first episode alongside The Mickey Mouse Club (I may be mistaken, but the closest Duke got to trading his cowboy hat for the famed “Mouseke-ears” was through Mouseketeer Jimmy Dodd who appeared with Wayne in the film “Flying Tigers”).

The age of confidence, optimism, and consumerism framed the year of cultural transition. “The Jack Benny Program” said goodbye to the radio for the teevee and never looked back — and millions of Americans came with him. This new sound was displacing the American Standards of the 1940s: Rock and Roll. Elvis Presley and his pomade appeared on screen for the first time in 1955 on the “Louisiana Hayride.” The film “Blackboard Jungle” premiered in March of that year with Bill Haley & His Comets causing a stir as they Rocked Around the Clock on the soundtrack. The J.D.s and rebellious teens were listening to and watching Elvis, Chuck Berry (who recorded his first single, “Maybellene,” in May 1955), and James Dean (who died in September and whose film “Rebel Without A Cause helped define a generation premiered that year, tragically also the year in which he died at age 24). It contrasts with the era’s more conservative side as “Oklahoma!” and “Lady and the Tramp” topped the box office, and William F. Buckley’s National Review magazine published its first issue. And of note, a young writer named Jack Kerouac would embark on his own cross-country search for America, and his place in it, in 1955. He wrote about it in his novel “On the Road” in the same stream-of-consciousness, eager, sprinting style as he wrote the introduction to Frank’s The Americans.

In their journey to “find” America, they understood that America’s ethos was to continually defy expectations, preconceptions, and bad attitudes.

The importance was in a willingness to throw themselves into a better understanding of America and conclude that it is an impossible task. Volpe recounts Webb’s journal entry, written just weeks after returning home on his 50th birthday, his trip now complete, discovering as much about himself as America and his fellow Americans:

Each person has a set of values — sometimes there is no realization of this. What are your values?...Owning or having things just for the sake of possession is meaningless to me now, But I am a miser about experiences…I don’t fit into this society too well. I don’t have the drives and ambitions to be a so-called success. And yet, I am a success. I have managed to nourish many of my needs — have realized many of my dreams — have never been bored. Unhappy yes — and lonely maybe frightened a little. But most happy and optimistic and alive.

Frank and Webb came away from this life-changing, formative experience not with a cynical eye at what faults they perceived or a falling short of perfection, or the judgmental attitude of those who believe their elitist, or insular, tunnel-vision of America is the unconditionally correct one. Frank complements Webb's optimistic sentiment, writing in U.S. Camera Annual 1958, “Criticism can come out of love. It is important to see what is invisible to others. Perhaps the look of hope.”

America is a country of curiosities and the curios. Unsettled minds and hearts determined to find what treasures lie in the next unraveling road, beyond sunburned hills, and beneath the thick mist of fog and unrealized daydreams. John Steinbeck wrote of that wanderer’s spirit in his novel Travels with Charley: In Search of America:

I saw in their eyes something I was to see over and over in every part of the nation — a burning desire to go, to move, to get under way, anyplace, away from any Here. They spoke quietly of how they wanted to go someday, to move about, free and unanchored, not toward something but away from something. I saw this look and heard this yearning everywhere in every state I visited. Nearly every American hungers to move.

It is in America’s restless nature. Looking to be settled but never settling. Americans, from the days of de Tocqueville to Steinbeck’s migration and the Beatniks’ listless wandering to Frank and Webb’s viewfinder closeups, are a tricky bunch full of contradictions and mystery — to be explored and greeted with hearty handshakes, comforting embraces, and long goodbye waves — not explained away, dismissed, condemned, or solved.

“I was halfway across America, at the dividing line between the East of my youth and the West of my future.”

― Jack Kerouac, On the Road

Jenna. As I read what you publish I think that you are a soul of a certain age, one that has been present in years past. One may say that you are “an old soul” yet you are so young. I always enjoy you insightful articles Jenna. Thank you.

Jenna, beautiful writing as I come to expect from you. It's such fun to journey through your post of searching and exploring America from a time when the fabric of America may have been vast and patterned, but tough and strong like tightly woven wool. I'm not old enough to have experienced the days you describe, but I almost feel as though they are my memories now! Thank you.