Men Without Chests

Literature, men, and stretching forth toward greatness.

Have we given up too easily? We have given up too easily. One would think a culture chock-o-brock with problematic men and toxic masculinity would never allow itself to be railroaded into submission by a crowd of lumpy, middle-aged, new-wave yonkers holding editor’s pens and jingling the keys to literature’s gates. But bad things happen when we decide something isn’t worth fighting for — whether that’s the integrity of literature or men or Truth or all of these things.

A certain womyn enters the old place — the one cordoned off from the street, set back enough you’d never see it in the hurry of places to go and people to see.

A short, big-faced woman in a floor-grazing, shapeless dress and tiny pack hanging around her bulbous shoulders. Rows of button pins line the straps, little shiny billboards of proclamations about sexuality, progressive ideology, militant feminism…

The big-faced woman turns her eyes to the front where half a dozen smartly dressed men sit on thick stools, the rest leaning on the polished wood bar top. They talk in loud confident voices and tell stories of college and sports and traveling to the mountains. They drink and smoke and argue, and everyone feels good. The big-faced woman pushes through the cigarette smoke and Sazeracs, swinging meaty forearms until she reaches the clean-shirted bartender, suddenly serious in the dimness. She shovels around in her pack and with a clenched hand fist out a copy of her master’s thesis, Trans-ing the Queer: Victimhood, Radicalization, and Warrior Princesses Against Toxic Patriarchal Literature.

“This,” one hairy-knuckled finger stuck in a man’s unbelieving face, “is my space now.”

So, what if a different woman enters? The one that took care to learn and live and fail at everything and nevertheless continues because now she has a son and a daughter. Both are tiny in the world, but they don’t know it yet, and I hope they never know it as cynical adults faced with closed doors guarded by unimaginative, scowling, key-jingling gatekeepers. If you watch them, the children act with innocent intent and totally without self-consciousness or inhibition. They explore with abandon, and time is meaningless. They grow into their surroundings and find wonder everywhere. Their world is incompatible with the one we’ve constructed, especially for men; especially for the men we need; especially for the kind of men that women need.

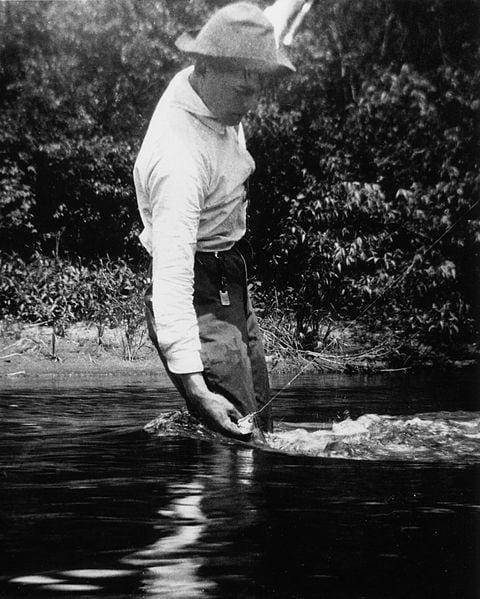

My maternal grandfather was a hard man. Not mean or cruel or quick to anger. The man I knew was wise and had strong hands. He cut his fingernails short and straight with his pocketknife. He had clear eyes that shined bright when mischief sneaked across his lips. He was hard because he was life-worn. He was a man, and he was quiet, and he loved and was loved.

He left the North Dakota farm where he grew up during the Depression to fight in the Second Great War. My grandfather was a hard man because he had to do hard things that he never talked about with me because I was a young girl. And I never asked him. He took my small hand in his confident one, and we took walks on the dirt road that ran to the highway. He taught me the names of the trees and the birds and never rushed.

I never understood him to be fancy or sophisticated. He liked his hamburgers plain and his beer cold. The men I admire most in this world have the same simple plainness. A quiet, understated masculinity that defies shape and containment. It runs clear and true like a wild stream.

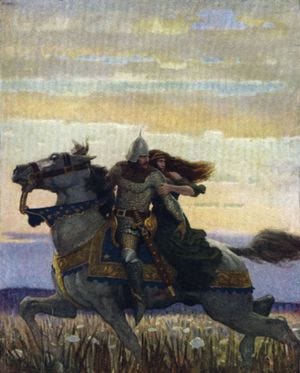

These are men who do hard things because they must. They do hard, risky, and dangerous things that won’t bring them fame or fortune but because it is what men do. The cowboy. The brother at war. The explorer. The leader. In stories, they were knights and pirates and warriors and sea captains. They ventured past the limits of safety and comfort and formed bonds at sea, in forests, through the plains, and over mountains.

There was no better place to foster this ethos than America. Where boys dreamed of rocket ships going into outer space and cowboys riding fast on the plain. And men wrote Moby Dick, Lonesome Dove, and Shane. We poured over The Great Gatsby, As I Lay Dying, A Farewell to Arms, and The Adventures of Augie March. We learned what it is to be an American at a particular place and time. It didn’t belong to any one person or group. It was us. Literature is the gateway to the unknowable. It unlocks the mystery of ourselves and our being. It doesn’t contain the answers but asks the questions. But we aren’t allowed to ask questions anymore, only present curated proclamations about uncurious and unmysterious boringness. Associative identity, perpetual victimhood, woe-is-me vomit buckets. This isn’t the recipe for nurturing greatness. This is no path toward selfless virtue. This is not a way to encourage the search, breaking away from the oscillating, unsatisfiable crowd. This is stifling of the American Spirit by the pusillus animus: small souls.

The small people fashion their self-importance by making themselves the arbiters of tolerance. They hate cannot tolerate ideas that contradict their own imagined view of the world. They have no interest in curating greatness — magnus animus, great souls — because it would expose their smallness and insignificance. They abhor the risk taker because it exposes their cowardice. We’ve left the fate of men in the hands of people who want to destroy them.

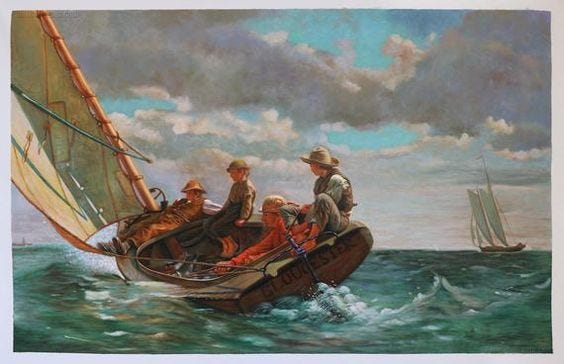

I’m going to pick on Ernest Hemingway here because his life and work illustrate the great arc of masculinity and literature and the toxic safetyism plaguing America. Great literature can offer objective truths and virtue as a tether that allows us to explore the world and our place in it. It is a channel from the harbor to the vast waters of a roiling, battling sea. We could be content with sitting in our safe harbors, leaving questions unasked, lands unexplored, waiting for others to tell us what to think and see and hear. Or we could take a story like “Big Two-Hearted River” or “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” and admire the simple way Hemingway reflects our lives.

I used to dislike Hemingway. I thought it was boring and colorless. I didn’t understand it — not because it was complicated but because it wasn’t. We make life complicated until the essential bits are unrecognizable. Love, beauty, truth, fear, hope. They are inextricably jumbled together in a tangled knot with no beginning or end. And we think nothing will make sense until it is all untangled and lays straight before us. But we do the tangling, and we refuse the way to untangle it all. It took me to become a life-worn woman to appreciate the masculinity, the understated richness, the easy vitality, and wonder that could only come from someone unafraid of asking the reader difficult questions — and expecting them to follow through. The writer and the reader have an elevated level of trust and courage. This isn’t something that can be force-fed by small-minded ninnies afraid of encountering someone with different viewpoints. This demands attention, courage, and questioning of the status quo.

A man who lives avoiding questions is a person who lives a fearful life. He lives for validation. A man who loves confidently, lives passionately and bravely, and pursues the mysteries of life lives for greatness. He does the hard things sometimes because they are hard, sometimes because they are ordered to do it by the convictions of their principles set down by a higher order. They are everything, and they are nada.

The chest is the seat of Magnanimity, C.S. Lewis writes in The Abolition of Man. He continues:

The Chest-Magnaminity-Sentiment – these are the indispensable liaison officers between cerebral man and visceral man. It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal.

Lewis believed that modern society produces "men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica explains magnanimity as a greatness of soul, a "stretching forth of the mind to great things."

We mustn’t give up so easily. We cannot let our good boys and men be stifled by the boring, unquestioning life. They need stories. They need stories to be written by them and for them — for us. When good men suffer, we all suffer. They do the hard things. Quietly, plainly, honorably. It isn’t for gatekeepers to sift through what ideas and views are “right” or “wrong,” acceptable or tolerant or just. That is the safe thing. Life isn’t meant to be safe.

I have this poem I’ve carried with me since high school. I’ve failed its essence a hundred times over but return to it, hoping for a time when I won’t. I think it fits here.

I have studied many times

The marble which was chiseled for me--

A boat with a furled sail at rest in a harbor.

In truth it pictures not my destination

But my life.

For love was offered me and I shrank from its disillusionment;

Sorrow knocked at my door, but I was afraid;

Ambition called to me, but I dreaded the chances.

Yet all the while I hungered for meaning in my life.

And now I know that we must lift the sail

And catch the winds of destiny

Wherever they drive the boat.

To put meaning in one's life may end in madness,

But life without meaning is the torture

Of restlessness and vague desire--

It is a boat longing for the sea and yet afraid.

—Edgar Lee Masters

Masters was a Kansan born in 1868. This poem is part of his Spoon River Anthology.

This is for Tony, Dan, Jim, and Allan for being clear and true.

I also want to include a musician who shared his courage and story and his gift with me some time ago. This is his album, “Take Our Dreams Away.”

Sincerely, Jenna

Do you have literature that inspires you? A story that embodies the courageous spirit or encourages the strive toward greatness?

This is a tour de force of an essay that you have written. Well done! Please keep up sharing the beautiful and compelling things that you write!

"A man who lives avoiding questions is a person who lives a fearful life. He lives for validation." Oh so true. Sadly, this describes my own father.