What happened and who’s to blame? The smooth-textured, frictionless experts only deserve half of it. The other half falls on us, in a sideways, tech-drift, drowning-in-the-algorithm TikTok scrolling kind of way. We got got, and we didn’t even realize it.

I’m talking about our sickly world that looks closer to the fluorescent-dim torture block interior recalling the opening scene of Joe Versus the Volcano (“Wow, Jenna that’s some reference.” – “It’s an oldie but a goodie!”) than the vibrant burst of pigmented eruption that runs through a scorching three-strip Technicolor Cinemascope rainbow and everything my dreams promised it would be.

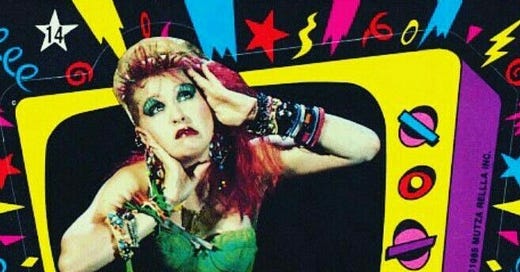

Do we find something appealing because it’s appealing (beautiful, striking, evokes emotion) or because it’s all we see, over and over, everywhere all at once? Do we realize we’ve sunk into a perception trance, only to be jolted into full aliveness when a bold, break-the-mold, aesthetic atomic bomb drops on us and the field is cleared of the mundane blah we’ve been zombie walking through for years? Behold the bomb and everything it symbolizes.

In the 1940s, America (and much of the world) was beholden to the artificial confines of aesthetic design. A world war can do that. But free the world from imperialism and fascism, and suddenly what was bound up in wartime drives and patriotic frugality exploded in optimism, American outer space manifest destiny, prosperity, and bat-out-of-hell unhindered possibilities. It was glorious. Neon signs, Googie architecture, starbursts and boomerangs, laminates, plastics, and moonshots. American style combined pastels and checkerboards, jukebox neon and Rock ‘n Roll, rocket ships and automobiles. This was the Winner’s Party and we were having F-U-N.

Then we overdosed on LSD, bad trips, bad music, poor decisions, and poor leadership and the culture hit the ground in a heap of psychedelic-colored vomit. Then the malaise set in, and we settled into brown tones, avocado green, and harvest gold — the 1970s version of our present-day grayscape. No Earth Shoe was immune.

In the mid-1980s, we snapped out of it. If the party wasn’t at our house, it was certainly next door and everyone was invited (except the Soviets and East Germans, natch). We were optimistic in a “Morning in America” kind of way. And how Americans feel permeates the cultural ether as an intoxicating gas that can send us into a maximalist, excess-driven euphoria or a stifling malaise.

Now it seems different. Now we’re sucked into the gray hole of purgatory where our emotions and thoughts are put into the meat grinder of technology. Everything is stuffed into the top, the algorithm cranks the handle, and out comes an extruded, homogenized slop. Ready for general force-fed consumption.

I’m going to refer to one of the great cinematic achievements in modernity: Back to the Future (and its two sequels). [I’m biased because these films hit the sweet spot of my formative years, and they were part of an era of entertainment that understood that so-called “family” films or television could be creative, engaging, and thought-provoking. There could be adult themes without explicit content or humor that wasn’t gross, and characters that had depth and evoked relatable, sincere emotions.]

A not insignificant bit from the trilogy is the roundabout way the 1950s mirrors the 1980s in its aesthetics and pop culture design. Neon lights, geometric shapes, innovative materials, and a helping of excess that went beyond functionality. Design was essential and thoughtful, whereas today’s excessively modern (gray) is anti-design, streamlined, simplified, and stripped of any character impurities or any character at all. It relishes — and even celebrates — its absence of design.

Just as Marty McFly visits Hill Valley’s diner, decked out in chrome and featuring shiny vinyl stools, a turquoise interior framed by nouveau-Art Deco pendant lights, he returns from the past to the future and goes to the Café 80s — a functioning time capsule that embodies the decade in its décor and demeanor. We see Max Headroom, exercise bikes, and Pres. Ronald Reagan battling Ayatollah Khomeini on a tube TV. But the design is the star. Bright colors, odd shapes, neon. It is bursting with Memphis Milano.

That’s right. The design aesthetic that ruled the mid-1980s through the early 1990s has a name and a most excellent history.

Memphis Design reimagined and spun the culture on its head, blending Art Deco with pop art. It was a happenstance of fate that a group of creative minds gathered in a small Italian apartment, Bob Dylan’s record “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” on repeat, and a supernova exploded:

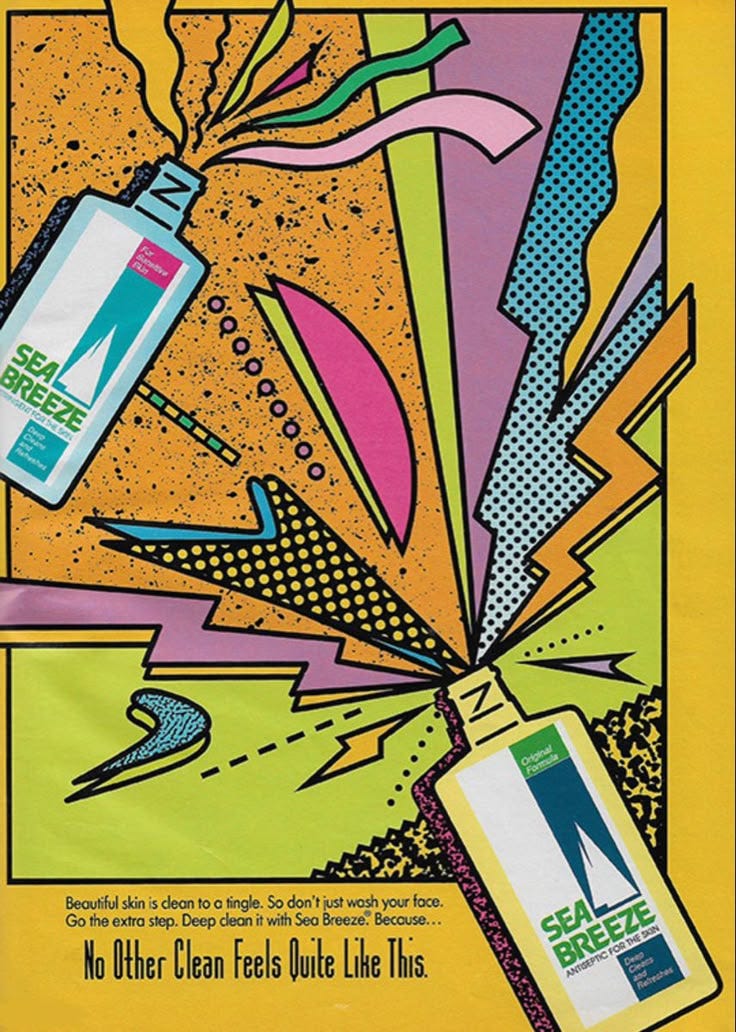

In the 1980s, a team of Italian architects and designers led by Ettore Sottsass, known as Memphis Milano, developed the retro design aesthetic known as Memphis Design. Because of their mutual dislike of the minimalist design style of the 1960s and 1970s modernism, the group of creatives set out to make postmodern furniture, fabric, patterns, ceramics, and other decorative objects inspired by art deco and pop art, bonding streamlined geometry and electric colors.

The Memphis Design style is a retro aesthetic that opposes brutalism and post-war architecture, interiors, and product design. In this manner, the Memphis Design style lends the streamlined geometry of Art Deco design and the electric colors of day-to-day objects. Memphis Milano is often described as kitschy and tacky because bright colors, geometric shapes, strong patterns, stripes, clashing hues, abstract designs, and plastic laminate characterize it.

The world was forever changed. These mind-blowing upheavals by men and women with an otherworldly sense of breaking through what we casually accept as possible — who disregard the limits of structured repetition —act as shockwaves of light waking us up to our humanity. The Memphis group “disliked modernism’s simplicity, its use of modest lines, bland shapes, and neutral colors.” It was a rude violation of “less is more” and adopting American architect Robert Venturi’s mantra, "More is more. Less is a bore." This is the design world’s version of the original punk rock.

December 1980 in Sottsass’s Milan apartment, listening to Dylan asking over and over if this really is the end, the world had no idea what it was in for. Maybe the design group didn’t either. Or they did, and they saw the wild technicolor patterned patchwork as the lifeline to a world being buried under the weight of its tedious dullness.

Memphis isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. It’s a young person’s bag (or your eccentric aunt’s). It’s bold, brash, and unrelenting. But it’s striking for the certain optimism, mischievous innocence, and playfulness that reflect the time, unlike the malaise that preceded it or the pervasive cynicism that followed. It didn’t just show up in chairs and room dividers. Memphis’s oversized design personality demanded an oversized impact. It was all encompassing, and it was because it became American.

The design and its Group were the consequence of inspiration colliding with the time. “With Memphis, forms balanced between pop culture, high culture and ironic classicism merge in products based on a flamboyant mixture of these factors. A disruptive aesthetic, between kitsch and elegance.”

As America was coming into its own cultural and economic revival, as consumerism roared back and youth culture began to rise, Memphis became the unofficial uniform. Fashion labels and brands adopted its characteristics. The Italian design houses of Versace and vintage Valentino experienced a surge in demand and Memphis Design rode the rising tide. Cultural and fashion icons David Bowie and Karl Lagerfeld became fast fans. It quickly made its way to the masses through ESPRIT and Swatch. Maybe you had a Caboodle or a Trapper Keeper notebook as a kid, a young Sofia Coppola probably did. Both were essential teenage tools for navigating middle or high school in the late 1980s, just as Miami Vice or Saved by the Bell was essential viewing. Both had Memphis fingerprints all over, as did that groundbreaking cable-TV channel that went on air on August 1, 1981, MTV, which used Memphis Design elements throughout its brand. And every American '80s kid remembers that goofy-sounding man-child Pee-wee Herman in his Memphis design-inspired playhouse. Memphis design was in video games, on Walkmans, print advertising, and of course fashion, television, and on film.

There’s also a small treasure that is absent today: a common cultural signpost. Back to the Future II’s Café 80s is memorable and fun because it instantly evokes a specific moment in time and the associated events and feelings in a universal, human way.

It’s a remarkable phenomenon when one idea’s whisper tumbles through the air, ear to ear, eye to eye, and emerges at the other end in a megaphone blast. No algorithm, just a few people making a cascade of decisions that turns into a tsunami of cultural togetherness. My favorite explanation of this is Meryl Streep’s cerulean sweater monologue from the 2006 film The Devil Wears Prada.

That last line, “It’s sort of comical how you think that you’ve made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you’re wearing a sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room… from a pile of ‘stuff.’” Who is making the decision now? Or, more precisely, what is making the decision? The difference now is the algorithm. The thing or technological things that fooled us into thinking we were making the decisions, or at least human-type people were in charge somewhere, of making the decisions of what we see, hear, or consume.

The seamless transition from perception to reality to algorithmic force-feeding until it’s the only thing we want to consume, the only thing we crave. The Frito-Lay dopamine effect used by mind-zapping, attention killers. Are you consuming for the pleasure, the satisfaction, or fulfillment? Does it matter? Does it matter what is real versus what you think is real?

I don’t know.

Maybe the graying-down of culture is meant to obscure the reality of things. To make it hard to discern what makes us feel alive and pull emotionally one way or another. To respond in a fully human way rather than being assuaged into a gentle nothingness — a comforting white noise, snack chip, clickbait, monotone buzz. Easier to control, easier to predict, easier to get the planned response.

The technology nightmare didn’t come as the science fiction writers warned. It didn’t come for us by hammering down the door in a moment of Terminator self-aware robot revolt or Colossus-style apocalyptic firestorm.

The subtle subversion occurred out of sight as it evolved, taking advantage of the temptation to let our minds run on autopilot. It allowed us to believe we were still in charge of it. I don’t know if incorporating more artificial intelligence, technological tools, or advanced automation is serving as a substitute for human intelligence, for undermining the creative process, or the process and result is wholly a consequence of our decisions (how much we allow it to influence us). Maybe there is a point of no return where the benefits are outweighed by the mind-numbing absurdity — an excuse to indulge our laziness. A way to streamline our minds into an unthinking, unquestioning gray blob.

In a recent post at The Lamp, managing editor Nic Rowan writes “The A.I. Mind Meld” about AI swallowing up language and culture and the pervasive mimicry of certain words and phrases:

It would be unfair to claim that the A.I. mind meld is confined narrowly to the twenty-five and under set. Everyone, myself included, is affected by it in some way. This is just how these things work. In his profile of [Ben] Rhodes, Samuels notes that once the advisor had achieved his mind meld with Obama, he made sure that everyone else following the White House merged their minds with his, too. It was not a difficult task: All he had to do was supply the words, and the press corps would repeat them as if they were original. Pretty soon everyone was repeating the same phrases in the same way. “They literally know nothing,” Rhodes bragged, and with his help, most knew even less.

I foresee something similar occurring when the A.I. mind meld is complete. More pessimistic observers will say this has already occurred. The thing works like a boa constrictor: as more people use L.L.M.s and come to rely on them, the range of expression narrows, especially when the A.I. of the future is itself trained on A.I.-written texts. The future of language will be relentless, groundbreaking, and elevated.

It's hard. It’s hard to consciously work against choices made for you. It’s hard to think outside the images and words blasted at eyeball-popping speed and frequency. It’s hard to explore the unseen world, think outside the parameters of “accepted” thought, and turn the world upside down, shake it a half dozen times, and pop the top. It might explode in your face. Or the world might benefit from a new level of perception and thought that reminds us of our humanity. It’s at once humbling, extraordinary, and daring.

The Memphis Design Group defined itself as “The group that succeeded in implementing the revolutionary intuition: creating shapes that blend in a crazy mixture with a disruptive aesthetic, between kitsch and elegance.”

Could a computer do the same? Would you choose it over the grayscape?

We have a choice.

Thank you for reading and being a fellow traveler.

Sincerely, Jenna

For those whose childhood was wacky, a little awkward, and a lot more free:

A rich and rewarding read. Thanks

I think every generation suffers from some kind of mind numbing awfulness but this AI's siren song seems to come with much greater things at stake. We are being given what which we wished for and it is the greatest ugliness wrapped in the greatest convenience. As a species we seem to gravitate to the worst and the best. thanks Jenna. Here's a poem you might like-https://westonpparker.substack.com/p/empty-hands