Nothing soothes a broken heart like watching two men beat the hell out of each other. It may not cure it, but the tender mercies can be assuaged watching sweat and blood pounded off a man’s body with the physicality of venom and singular, rabid determination.

So it was on Feb. 14th 2025 — this past Valentine’s Day — one night at legendary venue The Theater at Madison Square Garden in New York, Keyshawn Davis became a world champion knocking out Denys Berinchyk to capture the WBO lightweight title. Handily, in full technicolor, bright lights flashing off determined glares and barking cornermen — two men in the squared circle.

The packed house roaring with cheers and taunts and lit with waves of flashing lights and smiles. A show, the show. Midway through Round 4, Davis’s explosive left hook to the body dropped Berinchyk to the canvas. Struggling to get up on one knee, he couldn’t beat the count, and the knockout was clocked at 1:45. Davis captures the belt.

By any account, this was a decisive win. Davis as the victor wasn’t just the hometown hero against the Ukrainian professional. He vanquished a rival. His star is on the rise. A boxing tale; a sports tale; a human tale.

When it’s stripped to the core, boxing may be the best teller of the secrets of men. What makes the heart beat and what beats the heart. Every sport has its heroes and legends. But in the ring, nothing matters but the primal: beat or get beat. In his memoir, “Raging Bull: My Story,” boxer Jake LaMotta writes, “charge out of the corner, punch, punch, punch, never give up, take all the punishment the other guy could hand out but stay in there, slug and slug and slug.”

There is nothing left but the makings of a man facing his rival and himself. Winning or losing becomes the line separating living and existing — to expose yourself with your guts on display in front of cameras and crowds and God. And suddenly it’s not about glory or money or fame but meeting the caged animal and setting it free or die trying. Stand with gloved hands raised. “V” for victory.

For outsiders, boxing seems the embodiment of brutality. But it’s only a reflection of the reality of life. Only a few men are willing to enter the ring, leave every ounce of blood and sweat on that canvas while a roiling crowd jeers and hollers — onlookers to the struggle of man versus man versus himself. There is no room for error, no accommodating imposters.

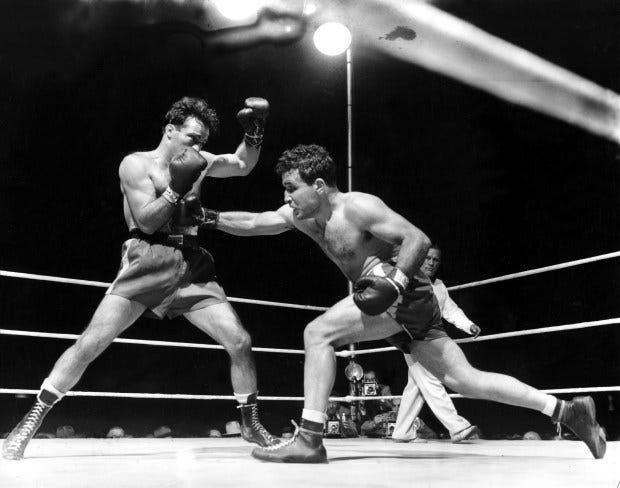

On a different Valentine’s Day, 1951, two men met for the final time in what would be known as the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre. It was a bout for the middleweight championship. Two men, brawler LaMotta versus the boxer puncher Sugar Ray Robinson — regarded as the best pound-for-pound fighter in history. The pair entered the ring six times over the course of their careers, but it was a fight that defined an era and, in post-WWII America, crystalized the brutality, rawness, and pain of Men in a nation and world longing to forget it.

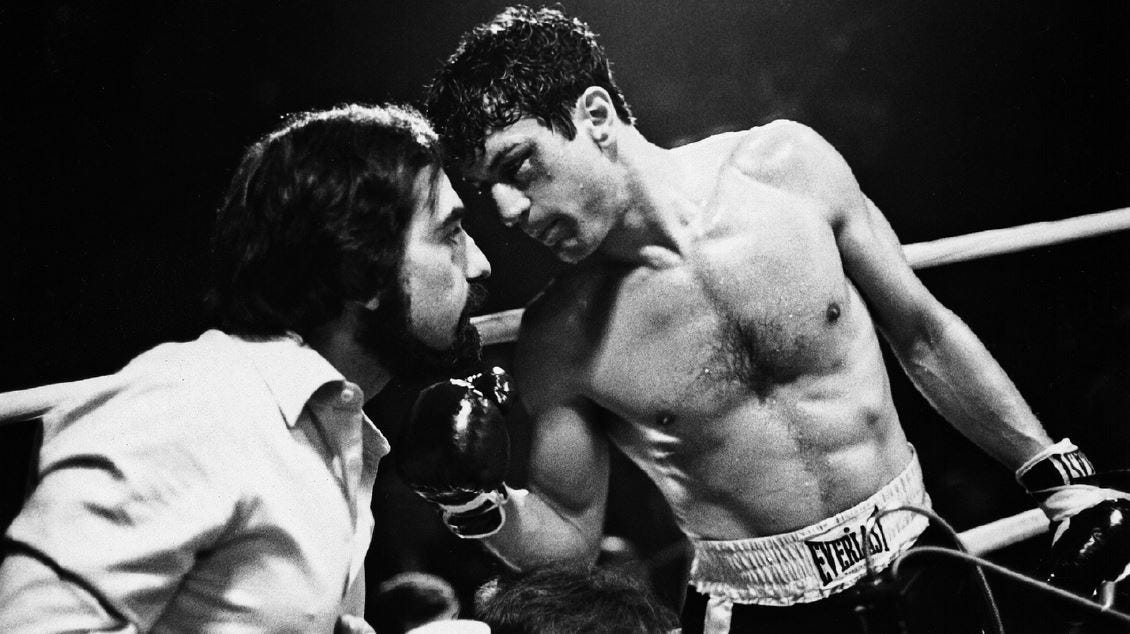

Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece, the 1980 film Raging Bull is a film about boxing that isn’t about boxing. This is apparent as soon as the singular figure of a robed Jake LaMotta fills the screen, framed by the ring, all cast in black-and-white while “Intermezzo” from the opera Cavalleria rusticana by Pietro Mascagni plays. LaMotta’s graceful, slowed motions in stark contrast with the violence and chaos that is about to unfold. Scorsese describes it:

I didn’t understand what the ring was. I couldn’t interpret it in my life… but I think at that time I was taking it too literally. Ultimately I came to understand that the ring is everywhere. It depends on how much of a fighter you are in life. The hardest opponent you have is yourself.

This is about the devil lurking in every man and the struggle for humanity in an often inhumane, solitary world.

It echoes boxing’s mainstay character-icon Teddy Atlas discussed the core of the sport on The Ring podcast. It is a window on the heart of the courageous and bold Man who strips himself of outward pretensions searching for his soul. A primal pursuit:

There's nothing wrong with the sport. It's nothing wrong, never was, never.

But two men getting in the ring, willing to go in that ring and leave that ring with less of themselves. Willing to go in that ring and find out things about themselves that they didn't know until they got in there. Willing to go in that ring and actually act as guides, explorers to us, to show us where a man can go when he has a reason to go there. To go into that ring and like your house — to me, your life, your body, your mind is a house.

How many doors have you opened and more important, how many doors have you not opened in your house? To go in your house and say I never opened that door, why? Oh, it was dark in there.

Yeah, but there might be something in there that you need to find. Yeah, but it's dark. I know it's dark.

Make it light. Open the door and find out what's in there. That's what boxing does.

And it gives us all a chance to be part of that journey, to learn, to be taught.

Great fighters do that. That's the funny thing.

They're not educated. No, no, they're the smartest people in the world. Because they teach us that valuable lesson of life: Go further.

There's a difference between living and being alive…between living and existing.

You sit in the dark and roll each moment that brought you to these tears and anger over and over. Put yourself through pain, self-destructive fury, turning the knife deeper, screaming at yourself and your stupidity and unworthiness until it consumes you and becomes you. You use that pain as punishment for everything you cannot be. And this is what we see in the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre.*

In the ring, taking a beating, toe to toe, nowhere to escape. Taking a beating because you deserve it. Taking a beating because finally the pain you feel on the inside is matched by the pain of your body. And you lean into it because the unwavering confidence in your unworthiness needs it. The punishment of fist after fist, body blows, hooks to the face — every cut and bruise and rupture is earned and validated by what you’ve told yourself for years: maybe I am an animal. Maybe I am not worthy of love.

If you grant yourself acceptance of any “win” or job well done, or victory, you will pay for it later. Joy has consequences. And joy — satisfaction even — is soft. It is satisfying the animal's hunger that must stay ravenous to stay alive. So, you tell yourself any victory was by chance. Luck. A fluke. You will never be good enough. An outsider in an insider’s world.

When you’re suffering, when you’re drowning in your brokenness, when there seems to be no redemption, that pain is the only thing that can keep you from destroying yourself. The fight is the only thing that can save you amidst the flashbulbs surrounding the canvas, the heat, the sweat, and the blood. Just keep fighting.

Except when there is no redemption through the suffering.

That is what made Jake LaMotta the animal that he tried to tell himself he wasn’t.

Scorsese’s genius in Raging Bull isn’t in the directorial choices he makes, not the striking black-and-white photography evoking the televised fights of the 1940s and ‘50s, not even in the Academy Award-winning editing by Thelma Schoonmaker. What makes the film profound and haunting and incredible is that Scorsese weaves all these elements — with powerhouse performances by Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Cathy Moriarty — into a reflection of the worst version of ourselves. And we cannot look away.

The film, like boxing, centers around a primal need to stay alive. And for LaMotta, and what Scorsese had to go through to decide to make the film, was that he saw a parallel to LaMotta's self-destruction mirrored in his own struggles with addiction. “Jake La Motta fought as if he didn’t deserve to live.”

I think this is a brilliant, horrifying, honest, brutal, and raw look at the soul of a person who has to confront his demons, to accept regrets, express remorse, to stop hiding lack of confidence, doubt, and feelings of perpetual inferiority.

Anger is the only thing left in a life that feels out of control — even as you try with every sinewed muscle laid bare by destructive self-loathing to grab it back. That is the pain you hold on to like some masochistic security blanket and inflict as much pain inward as outward. But you deserve it. Don’t you? Like the abused partner in a relationship, portrayed with brutal rawness by De Niro. You feel you need or deserve the punishment because you said the wrong thing or reacted the wrong way.

For someone who cannot stop or change the self-destructive tape that runs at a constant, gnawing buzz in your skull, the pain is the thing. For LaMotta, it is a substitute for a path to redemption and receiving the grace you refuse to give yourself. So, he turns that fury and destruction outwardly even as it keeps him trapped in his animalistic rage. He never apologizes, there are no introspective, transformative moments. He is lost in it, even as he denies he is in the midst of it.

That is the difference. That is the cautionary note. We cannot look away because if we do — if we deny that part of ourselves can exist — we are lost.

Scorsese had a different vision, one that I’m painfully familiar with. He told an audience at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival, “I was lost in a way, so I had to start all over again.”

He continues:

For me, it was a culmination of everything I desired to do, and I made it as if it was pretty much the end of my life… [a] suicide film. I didn't care what happened to it. I didn't care if I made another movie. In a way, it wiped me out, meaning that whole style of filmmaking. I had to start all over again. I had to learn again. Every day on the shoot was like, 'This is the last one, and we're going for it.'

At some point, your eyes open and you realize you must start living. Beyond the pain, beyond the anger, beyond every regret and anguished decision — wrong decision — and each opportunity you let pass in some narrow-minded frenzy. LaMotta isn’t just a cautionary tale of becoming the animal you kept feeding with your insecurities and blindness and rage. It is a window into the deepest part of yourself that will be if you let it. LaMotta refuses to see it. Scorsese shows us a way out through his suicide film. Jake LaMotta loses it all. Scorsese shows us how to find it.

Writing the script, De Niro and Scorsese decide to close with Jake LaMotta, since retired from boxing and running a one-man club act. The final scene is in 1964, with Jake sitting in a backstage dressing room reciting the infamous "I coulda been a contender" Marlon Bando monologue from On the Waterfront to himself in the mirror:

You don't understand! I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody — instead of a bum, which is what I am. Let's face it. It was you, Charley.

He refuses to own his mistakes so cannot be redeemed. He doesn’t change. He leans into the inflicted ego wounded by everyone else. Maybe deep down he knows he is an animal, but he cannot give an inch to the internal conflict of the human condition, humanity, and its requisite grace and forgiveness and tenderness. He cannot accept that it was his rage that led him to this life.

The end title card features a Biblical quote from John 9:25, a tribute by Scorsese to his NYU film school mentor Haig P. Manoogian, who passed away at the end of Raging Bull’s production:

So, for the second time, [the Pharisees] summoned the man who had been blind and said:

"Speak the truth before God. We know this fellow is a sinner."

"Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know," the man replied.

"All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see.”

So, we return to Teddy Atlas and the fighter “Willing to go in that ring and actually act as guides, explorers to us, to show us where a man can go when he has a reason to go there.” We have to have a reason to see. A purpose and faith, giving ourselves entirely to grace, vulnerability, and life lived bare, stripped of anger, and break the shackles of self-destructive doubt and insecurity. Only then can we see.

*This is the real footage of LaMotta’s final fight with Sugar Ray Robinson, Valentine’s Day, Feb. 14th 1951. The final three rounds show the brutal beating LaMotta receives from Robinson’s unrelenting punches, yet he refuses to go down — 31:46 mark is the 11th Round bell. In Round 12 we hear this commentary:

One minute to go in the 12th Round. Robinson is merciless, keeps looking at the clock.

No man can endure this pummeling. Row after row after row from the Ring the crowd is standing and cheering. LaMotta is just going to catch it with a half a minute to go, mouth wide open left, eye bleeding.

The round is almost over. There's the bell ending the 12th round. The huzzahs of the crowd — listen to them. Round number 13, the hard luck number.

My only note is that this reflects self-directed self-destruction and the escape from it. It does not describe my relationships, except for the tumultuous one with myself. Thank you for sticking with another long post, one I hope helps a blind man see.

Sincerely, Jenna

This was incredible—it made me rethink everything about the John 9:24-26 final title card, which I now believe is the most potent moment Scorsese invoked.

Paul Schrader once wrote:

"I don't think it's true [his redemption] of La Motta either in real life or in the movie; I think he's the same dumb lug at the end as at the beginning, and I think Marty is just imposing salvation on his subject by fiat. I've never really got from him a terribly credible reason for why he did it; he just seemed to feel that it was right."

But reading your post, I realize that John’s verse isn’t just an addendum—it is the most credible moment in the film.

La Motta may still be living a lie, but that doesn’t seem to matter to God. God loves him, and somehow, someday, in some way, he will be redeemed. Maybe that truth lifted a burden off Scorsese’s shoulders—just as you pointed out, it allowed him to take the artistic risks that define the film. He handed himself over to God, and that was enough.

Thanks for leaving it all out there, Jenna. I read this with rapidity. The variety and quality of what you write is amazing.