“My theory is that the purpose of art is to transmit universal truths of a sort, but of a particular sort, that in art, whether it’s poetry, fiction or painting, you are telling the reader or listener or viewer something he already knows but which he doesn’t quite know that he knows, so that in the action of communication he experiences a recognition, a feeling that he has been there before, a shock of recognition. And so, what the artist does, or tries to do, is simply to validate the human experience and to tell people the deep human truths which they already unconsciously know.”

—Walker Percy, Signposts in a Strange Land

Was there ever a time when politics didn’t inform in some way, the arts? Perhaps it’s always been a thread running through the kaleidoscope world of literature, music, art, and theater or film that leaves a perceptible imprint on our outlook. But in a way that has become too forcefully thrust upon us, art has been swallowed by the political narratives of a modern society obsessed with its own insecurities and image.

Long before “woke” entered the popular lexicon, became a virtue signal of the left, and finally a reactionary weapon on the right — and in terms of art, a bright line separating a side more invested in the perception of compassion and equity from a side obsessed with countering it through an equally cringe-worthy process of displacing art with political messaging — just from a different team.

In his 2014 National Review essay “Let Your Right Brain Run Free,” Adam Bellow writes,

The late Andrew Breitbart understood the importance of popular culture and was determined not to neglect it. “Politics is downstream from culture,” he famously said, and he continually called upon conservatives to quit griping about liberal media bias and do something constructive instead. Write your own books, he exhorted. Record your own music. Make your own movies. Everyone agreed that this would be a great idea. But no one knew how to go about making it happen.

Well, guess what: Andrew was right. The conservative counterrevolution is coming. Indeed it is already here. It’s just that most conservatives haven’t noticed it yet. It came to my attention only because of the position I occupy in the New York publishing world.

But what transpired in the near decade since this was written, was not, perhaps, the vision of small-c conservative art and cultivated culture that Bellow or Breitbart envisioned. What we are seeing is simply two ideologies battling each other using political narratives in a weaponized platform.

One doesn’t have to look far to find the root of what publishers are willing to pursue in those rare times they stray from their legacy money-makers; and it’s not original, daring, or unique and niche writers that are devoted to storytelling and the principle of the art. Twitter has a section devoted to Manuscript Wishlists (#MSWL) full of whoppers like this:

The conservative response to counter this type of identity vanity show shouldn’t be to do the exact same thing with the mentality that just because the fruit of their effort is from a conservative tree that it is any less poisonous. It’s just as cringeworthy, just as painful to swallow, and just as bad as its progressive counterpart.

The lesson to be learned is never to start with a message and attempt to create “art” around it. Let the artist, through the medium or platform, interpret what people already know as true, virtuous, and beautiful. These are ingredients that are inherent in the conservative tradition and are in opposition to a post-modern upheaval that requires re-education through indoctrination or intense social pressures.

In his counterpoint to Bellow’s essay, “Conservative Fiction and the Culture Wars,” Seth Mandel writes in Commentary, “Bellow is right that conservatives should be creative and their creativity supported. But I think it’s worth pointing out that often ‘liberal’ or politically neutral novels reinforce conservative ideas. The same is true of movies and television, though Bellow concentrates on the written word.”

The opening Walker Percy quote I used illustrates this, as does a longer essay he wrote in Harper’s from the June 1986 issue:

In any case, what is being explored and set forth in this kind of serious novel is not primarily the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie or the wasteland of Los Angeles but the fundamental predicament of the character himself or herself. Accordingly, what is being explored or should be explored is not only the nature of the human predicament but the possibility or non-possibility of a search for signs and meanings. Depending on the conviction of the writer, the signs may be found to be ambiguous or meaningless-or perhaps a faint message comes through, a tapping on the wall heard and deciphered and replied to.

The point is that all fiction can be used as an instrument of exploration and discovery, in short, of sciencing. In a new age, when things and people are devalued, when meanings break down, it lies within the province of the novelist to start the search afresh, like Robinson Crusoe on his island. The novelist or poet in the future might be able to discover, or rediscover, how it is with man himself, who he is, and how it is between him and other men.

What is so tragically lost in this Culture War front is the objective nature of art, a sustaining truth, and the creation of beauty and its transformative and redeeming qualities. But it is not an accident that this degeneration has taken place, especially in the literary sphere.

Words are dangerous. And great works of literature that have endured an ever-changing world are perhaps the most dangerous. They symbolize the unchanging reality of human nature; it’s a blasphemous act to believe that that exists at all. Permanent things — objective truth — runs counter to a progressive agenda in which history can be rewritten according to day-of-the-week rules. This very narrow worldview hasn’t produced great art. The only thing it accomplishes is what it sets out to do: set the parameters of acceptable opinions, thoughts, and social norms, dividing society deeper into the compliant versus the problematic. Great art, on the other hand, presents the human soul as an entity wanting meaning and purpose. It examines the very nature of things and connects us together because of our common humanity — the failings, the struggles, the hopes and desires.

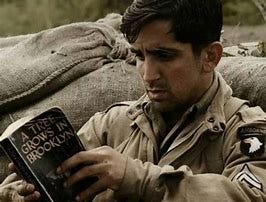

One of the great American novels of the 20th century, Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn illustrates this. Published in 1943, the book follows a young girl in Brooklyn as she navigates coming of age in a hard city and harder time and experiences heartbreak, fear, loss, and finally hope. It was so popular it was released in an Armed Services Edition — sized to fit in the pocket of the uniforms of U.S. troops fighting in WWII all over the world. What could a young man fighting thousands of miles away from his homeland find so compelling in such a story? Because its narrative doesn’t exist to check a box about feminism, sexuality, or leveraging some other identity grievance to stir divisive emotions or shame. The story is ultimately about the human will to survive, persist, and overcome seemingly insurmountable odds. It’s about hope and finding the American Dream. One Marine wrote a letter to Smith expressing his gratitude, “I can’t explain the emotional reaction that took place in this dead heart of mine. A surge of confidence has swept through me, and I feel that maybe a fellow has a fighting chance in this world after all.”

For conservatives then, the task is clear: It is time to stop lingering on the hypocrisy of the left, to complain about its stranglehold on the culture, and begin to take seriously creating great art. The hypocrisy will never end so top obsessing over that battle. The way to counter bad art is not to point out how terrible it is or to come up with a hackneyed conservative version of a political medicine show but to earnestly go forth confident in the timeless themes and ideas that have informed our previous distinguished creators. People are hungry for deeper connections to better understand themselves, the time, and each other. They are tired of the atomization of being. They are waiting for a path out of purposelessness and away from lurking despair and exasperation. People want to see and read about their common struggles and fears and see that they aren’t alone and that happiness and fulfillment are possible. And to hell with “cancellation.” Get over it. Conservatives need to stop indulging weakness.

If conservatives set out with the goal of making great art first and foremost and set aside political ends, the rest will fall into place. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat related this to his tribute to writer Joan Didion after her death in “Try Canceling Joan Didion,” “But like many great writers, she doesn’t belong just to the ideological faction she happened to align with late in life.”

And in his book, Art + Faith: A Theology of Making, artist Makoto Fujimura describes the art of creation and explains the importance of art as a way to express the human condition and how it can shape our worldview:

To know an artist is to know both the depth of sorrows and the heights of joy. Therefore, we need to consider the arts as a way to value life’s mysterious details and as a way to train our senses to pay attention to the world. The discipline of the arts allows for this luxurious communing to take place in the deeper soils of all our lives. Artists are the conduits of life, articulating what all of us are surely sensing but may not have the capacity to express.

But how do we reclaim the culture through art? Legendary television writer and producer Rob Long tells The Federalist’s Emily Jashinsky the secret (which has managed to elude conservatives for decades):

If a third of the young conservatives writing culture opinion pieces just stopped and instead wrote movies and television and novels, everything would be so much better. That's how we reclaim the culture. People ask, ‘How do you get the culture back?’ That's how you do it. You create it. You actually contribute to it instead of contributing to culture criticism, which has always been fringe — you actually make a thing.

And say you have a work of art or a piece of culture — getting Tucker [Carlson] to talk about it is not the goal. The goal is to get Stephen Colbert to talk about it, get the other side to talk it, because that's how you get the culture back. The only way to do that is to make something great, just make it great. That's all. That's easy. Just write a great book. I think conservatives have taken this pill or digested this falsehood that creative people are all Marxists, or you have to be a certain way to be allowed to get permission to make a movie or a TV show. And that is simply not the case. Do not wait for permission. Go and do it.

Just make great art.

Van Morrison's newest album, WHAT'S IT GONNA TAKE, has amazing lyrics, great instrumentals, and, of course, his legendary voice. The problem is that the WOKE are so filled with hate that they will not listen to it or buy it. We live in such a polarized world that Michaelangelo or daVinci could be alive and creating masterpieces and yet, if their political views were known, half of the people in our propagandized and poisoned world would ignore it.

America once had a vibrant and creative culture. The movies were better in the forties and the music was best in the fifties and sixties. Our minds have been poisoned even if we haven't taken the clot shots.

How do we even define American culture? NPR said that the song Wet-Ass Pussy was the best song of 2020 (that's our tax dollars at work, by the way). Worldwide, we see examples of art, literature, and architecture that can no longer be reproduced. Let's face it: America is a whale stranded on a beach. It was a great experiment, but it is over.

And just a thought............need it be called "conservative" art? I just think that puts on a label that is not really necessary and it becomes charged with what can be easily be labeled as negative associations. Words are important and they are being cannibalized these days. How about just great art and leave it at that?