“Every man has two deaths, when he is buried in the ground and the last time someone says his name. In some ways men can be immortal.”

—Ernest Hemingway

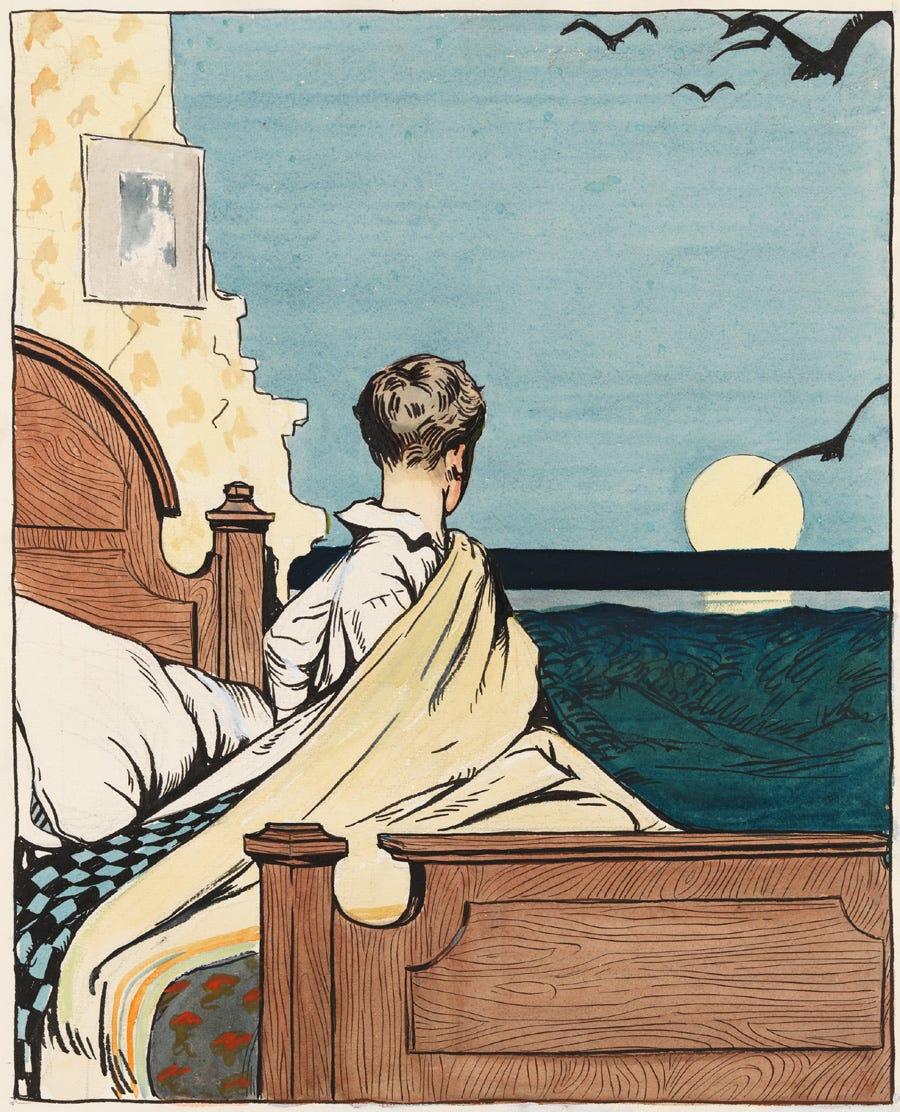

If you sit in a place long enough as a child with a wandering imagination, you end up recreating the outside, adult world as you with it, believe it, suppose it to be. Perhaps it’s a collection of stories from family who, on those long holidays gathered at a patriarchal residence, are spent reminiscing about life in their time, in their town, through a smudged, worn, looking-glass rearview. Or the world is pulled through the twirling tendrils and thunderous beats of music, or the meandering plots that seed the imagination like dandelions across an open field in movies or television: that plastic-framed bubble of sight and sound that worms its way into your emotions, dispensing caricatures of actual life — more hyperbole than realism: the noble cowboy, the wistful lovers, the romantic adventurer, the tragic hero… All of the characters converge to blend their stories into a reel of hyper-color sharpened through a prism of an immature mind.

Then, there are books.

As close to immortality that doesn’t persist on a screen, in technological storage, or on the lips of curators whose inevitable death will end the trail that he set out to reinforce from the ravages of time and modernity so vehemently. But books, novels, and stories set out from one’s vision of the world will be passed down to others in a dialogue so intimate and yet exciting as to carry the weight of a thousand lives and experiences within the binding containing nothing more than strings of an alphabet. Because if it touches you, if the author’s words hang silently on your lips as to make speaking any words seem futile and petty, it’s as if you can look directly at the sun without being blinded, letting the warmth and brightness radiate through your eyes and forever shape your worldview. And that is the immortality of literature.

It is never the same; it never shines in the same colors or intensity from one reader to the next, but it ever evolves through the times it is thrown into context.

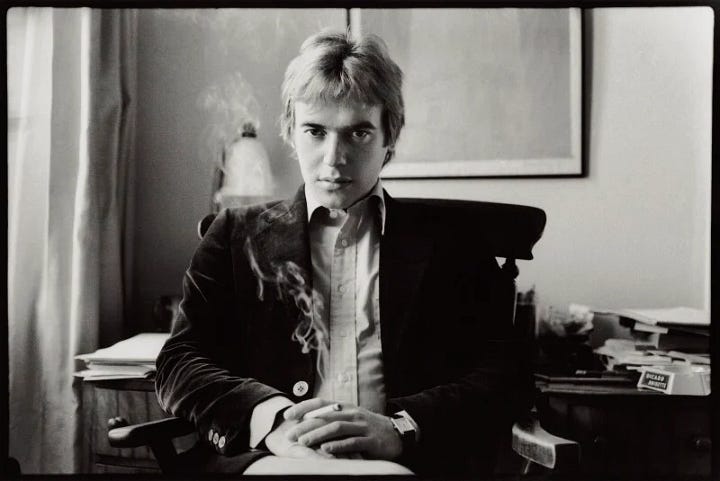

The late novelist, essayist, and social observer Martin Amis stated in a November 2020 Intelligence Squared interview, “I think there is a quite firm contract between writer and reader, and there are dozens of little correspondences, that the reader —no two readers have the same image of Madame Bovary — the reader is an artist and no two conceptions of the character will hold, and it’s a collaborative form in that sense — interactive.”

What a gaping hole left in the world when we have lost the great satirists. What we need more than anything — perhaps the one thing they could never give us — is a satire of death because it is worshipped out of complete fear in the face of hopeful immortality.

Amis’s shrewd, unaffecting eye knew no bounds in a quest to find immortality through the reader. He steadfastly held the understanding that dialogue was necessary to shape a story for each person tracing the words he outlined. There was no better way for an imagination to reach self-awareness, extended through endlessly shaping the visions of readers who found themselves in a place where they belonged.

He offered a look into the world he was a part of without being of it. Perhaps Amis was the cynical adult relative from our childhood that came by for funerals and, taking his place in a seat just one removed from the family, cigarette lit even before he sat down and nodded knowingly about your future even before he bothered to misremember your name. Yet when he spoke, it came out in a phrase of puzzling knowledge that never struck you with how bitingly right it was until years later when you grow up and realize you now occupy that world. He was steeped in the world of John Self, a witness to the world of his formation but not a willing contributor to it.

In his novel Money, Amis writes, “When the sky is as grey as this — impeccably grey, a denial, really of the very concept of colour — and the stooped millions lift their heads, it's hard to tell the air from the impurities in our human eyes, as if the sinking climbing paisley curlicues of grit were part of the element itself, rain, spores, tears, film, dirt. Perhaps, at such moments, the sky is no more than the sum of the dirt that lives in our human eyes.”

Amis continues,

Television is cretinizing me – I can feel it. Soon I’ll be like the TV artists. You know the people I mean. Girls who subliminally model themselves on kid-show presenters, full of faulty melody and joy, Melody and Joy. Men whose manners show newscaster interference, soap stains, film smears. Or the cretinized, those who talk on buses and streets as if TV were real, who call up networks with strange questions, stranger demands...If you lose your rug, you can get a false one. If you lose your laugh, you can get a false one. If you lose your mind, you can get a false one.

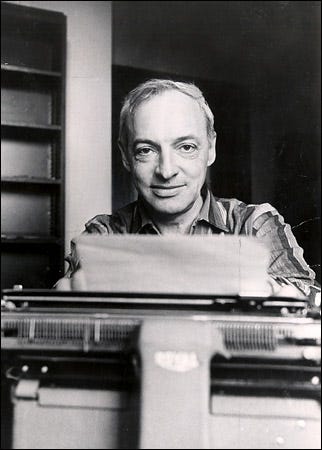

And we realize it’s a challenge, always. Like his mentor and friend Saul Bellow who charted the path in The Adventures of Augie March, it’s a challenge to shudder away the shackles of taking death too seriously to enjoy the life we are given and in doing so, missing the things that make us live. The big ideas, the immortal lessons, the passage of time — all these things combine to a thoughtfulness and contemplation that get lost in the hysteria of a world so tangled in politics, divisive identity culture, and cancellation as to make happiness and fulfillment absolutely inextricable from the suffering that happens when one tries so hard to cheat death. A culture of safety and protection from offense, rudeness, boldness, adventure, imagination, exploration, courage, virtue, and honesty. We lie to each other about death to shield us from the inevitable. What is more ripe material for satire than that?

We are trying to look inward to our immortality when we need to look outward. In our cities, in our communities, our friends and family. The world we try so hard to insulate ourselves from is there waiting for us to dwell in it and shape it and make it our own. Amis wrote the introduction to Penguin Random House’s 1995 edition of March — which was also published in the October 1995 issue of The Atlantic, expounding the virtues, hardness, and pilgrimage contained within Bellow’s work, what he (I think rightly) considers the Great American Novel and its essence of Americana:

As its culture was evolving, and as cultural self-consciousness dawned, America found itself to be a youthful, vast, and various land, peopled by non-Americans. So how about this place? Was it a continental holding camp for Greeks, Jews, Brits, Italians, Scandinavians, and Lithuanians, together with the remaining Amerindians from the Ice Age Mongolia? Or was it a nation, with an identity—with a soul? Who could begin to give the answers? Amid such diversity, who could crystalize the American experience? Like most quests, the quest for the Great American Novel seemed destined to be endless…As with the pursuit of happiness, the pursuit is the thing; you are never going to catch up. It was very American to insist on having a Great American Novel, thus rounding off all the other benefits Americans enjoy.

Is that what we seek as we read about Bellow’s Augie and his attempt to embrace a hard world in Chicago, even as he kept hidden a soft heart? That some part of us longs for the innocence of childhood where our imagination charts our path, not fear? That we retain some ember of fire lit in the comfort of familiarity and protection — that fuels a fire allowing us to leave it in pursuit of the world we hope to encounter? We don’t. But shouldn’t it be possible to make a small space that we can have of our own? To now be a part of it and be of it? The writers of the great novels lead the way through the satire of a cynical, fearful world, clearing the path for those led by their hearts and souls, not their petulance.

Amis, Bellow, Christopher Hitchens, and Tom Wolfe — writers who understood the value and impact of their words to a culture increasingly devaluing them. Immortality was at stake. Maybe for them, but for generations who defied the path of sameness. A world of homogenous gray cement blocks built not by the strength of oppression or tyranny but by the atrophy of courage to live. Bellow writes in Humbolt’s Gift, “Death is the dark backing that a mirror needs if we are to see anything.”

By knowing death, understanding the untenability of immortality, and choosing a life of constant pursuit bound only by the limits of the imagination around a nonsensical world, we can write our own story and perhaps find ourselves so close to the delicate perfumes of immortality to breath it in with our last breath.

In his closing remarks in the Intelligence Squared interview Amis says,

Writing is a universal aspiration for those inclined that way. And it’s to do with that time in life when you start to commune with yourself…and suddenly you’re having a conversation with yourself that’s on a higher level than anything you’ve known before, and it’s exciting and stimulating. So, I think it’s in all of us. And my ideal reader is young because that sort of guarantees a kind of immortality — delays my absolute death in that I’ll go on being read a bit after I’m gone. The quest for immortality or extended life is, I think, in the end, universal, and it’s why we have children so that the story doesn’t end — that it does continue.

We simply must keep pursuing our own pilgrimages, ever in pursuit of the place where dreams and imagination meet truth.

Time is our most valuable commodity, a priceless treasure we generously share, knowing we can never recover our investment outright. I appreciate your readership. Please leave a comment if you feel so inclined — a dialogue is the highest praise I can receive in exchange for your expensive gift of time. Sincerely, Jenna