I don’t have much to add to the current state of America. 2023 has ushered in — depending on where you stand, swing, or lie down in despair — the best of times and the worst of times to quote an author not of an American breed. And yet it seems to be the perpetual story of our nation: the best of times made of the worst of times; a prevailing notion that great divides are also the points where two sides meet. North and South, East and West, working and an elite class, urban and rural. It’s living in a country that has turned hostile to its identity while millions claim it as their own and a thousand notions of the idyllic life all contained but unrestrained under the umbrella of what we know as home. It is both a journey from it and a pilgrimage to find it.

Americana spans this journey. Its lore and ethos represent the home for the homeless and a foundational bedrock of cultural and generational continuity. It is where the Prodigal Son can return, even as the 20th century — now into the 21st — is marred by upheavals and tectonic shifts in attitudes and social mores. No matter how much we curse our traditions, condemn our parents, and renounce our history, somehow, we find our way back. Americana is the guardian at the gate of mystic idealism — that glinting reflection of fragments of deep spiritual revival, homespun authenticity, and earnest belief in prevailing Truth.

We are at the doorstep of the Americana Counterculture revival that is everywhere but nowhere, an ethereal sentiment of coming home.

If Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” was the folk answer to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” the countercultural revolution of the electrified psychedelic 1960s, Free Love freak-out, Turn on Tune in Drop out Leary-ism LSD mania was the swinging pendulum that resembled a guillotine at the neck of mainstream and Mainstreet post-WWII U.S.A. Fifty-four years ago last week, nearly half a million young people made a pilgrimage to the three-day music festival on a farm in upstate New York known as Woodstock. What was meant to be the defining moment of 1960s counterculture turned out to be the end. LSD was soon outlawed in the United States and England. Charles Manson’s bloody terrorism fueled an anti-hippie attitude. Popular bands Cream and the Beatles that absorbed the psychedelic sound broke up, and emblematic musicians of the genre — Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison of the Doors died tragically early deaths.

The technicolor explosion of flower petals and psychedelics was ending as Love-Ins were being swallowed by campus radicals and sit-ins smoked out by militaristic brimstone anger and unrest. Under it all, as the 1967 Summer of Love was in full bloom, the cultural wheel was turning, quietly steering a revivalist ship. Bob Dylan, the darling of folk and spiritual successor to Woody Guthrie and John Steinbeck, refused to obey the era’s rules by cultivating his own identity rather than be the embalmed corpse of a vanity movement. Gram Parsons was headed in his own, albeit parallel direction — first with The Byrds’ 1968 album “Sweetheart of the Rodeo,” then forming his own band, The Flying Burrito Brothers (releasing their first album, “The Gilded Palace of Sin” in 1969) and a sound he named Cosmic Americana.

Robbie Robertson of The Band captured the true meaning behind the new old sound: the direction of music and culture that signaled an authenticity and American pureness that hippies attempted but couldn’t altogether appropriate — revealing their singular arrogance of condemning previous generations’ traditional lifestyle and moral vision as completely wrong without the understanding or wisdom behind the roots of those traditions and morals. Robertson says in a 2017 MOJO Magazine interview:

We didn’t play by anybody’s rules and when everybody was going in this direction of wearing big polka dots and silly clothes and screaming hate about their parents, The Band was taking pictures with our parents. We were dressing the way we dressed every day. Not because it was a look, but because we lived up in the mountains and you couldn’t wear polka dotty clothes – you’d look silly at the hardware store. We came from our own past, our own realness, and our own honesty.

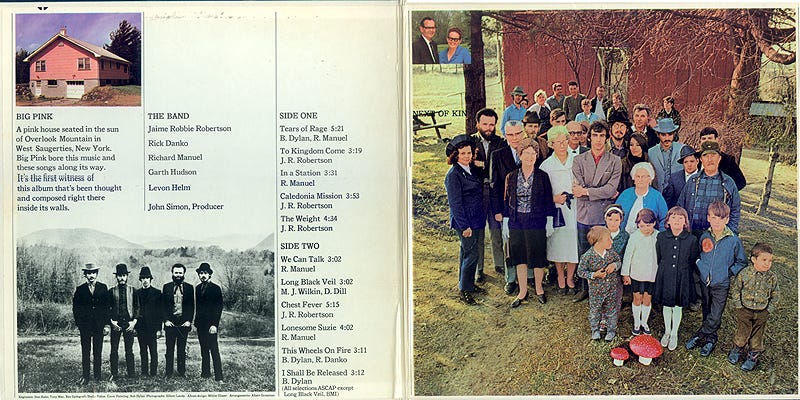

“Music From Big Pink,” The Band’s 1968 debut album, was the reactionary bomb that had been set in motion for decades. It was the antidote to the poisonous chaos borne of one counterculture, becoming something of its own; a revivalist redemption quietly feeding the roots of a timeless American spirit: plaintive words, familiar and humble stories, moralistic yet fallible characters, and performative simplicity. Four Canadians — Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson — and Arkansas-born American Levon Helm made their pilgrimage across America to find it and fathered an enduring era of Countercultural Americana.

The Band had been touring for decades in taverns and bars in the South with Ronnie Hawkins and later with Dylan as his backup band. They absorbed their surroundings, congealing it with what they separately then together found along the Mississippi, the Delta, the Appalachian Mountains, and hidden bluegrass, blues, and rockabilly temples across the country. It was as much a musical epiphany as a spiritual one. Hudson’s pulsing organ, Helm’s steady drum, and Danko and Manuel’s haunting vocals over Robertson’s unparalleled guitar invoked the church hymns of the previous century and solid traditional roots and country and western style — a stark contrast to the nonsensical dreamscape of incense-infused psychedelic rock. Together, Dylan, Parsons, and The Band built a house where there wasn’t one; a place of rest for those who, through music, still believed in America. A place that could create sound instead of noise, see themselves reflected in a common if flawed history, find value in struggle and face it head-on rather than dismiss it out of hand as a poor person’s lament. When the 1960s ran from the wisdom and tales of their elders, they honored them.

The Band posed with their spouses, children, parents, and “next of kin” on the inside cover of Big Pink. Dylan’s 1967 album “John Wesley Harding” was a stripped-down, roots-infused tall-tale mythos of the journeyman returning home. “‘The album has a quality of serenity about it which is not only charming, it is entrancing. The country music station plays soft and you hear the echoes of all those late night broadcasts: ‘friends and neighbors wherever you are, come on out tonight . . .’” writes Ralph Gleason for Rolling Stone in February 1968. Parsons and The Byrds cover “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” in Sweetheart, a song conceived by Dylan and The Band, eventually released in “The Basement Tapes.”

Americana forms the bedrock of a country that bids the pilgrim fare-thee-well but will always welcome us back no matter how much we sin against her. People mercilessly attack the very idea of America as a chimera or a worn-out fable for silly-headed children and misty-eyed faded patriots. But America and Americana endure and endear – if not as the Promised Land, then as the Land of Promise. We continuously hold ourselves to a standard set by the defeats and triumphs of past wars. Yet those who ball their fists in sanctimonious rage, constantly judging the existence of an imperfect past with a lily-white-washed conscience as if our story isn’t theirs, are just as ignorant and backward as they imagine their backwoods brethren to be. Greil Marcus writes in his 1997 book Mystery Train:

The songs were made to bring to life the fragments of experience, legend, and artifact every American has inherited as the legacy of a mythical past. The songs have little to do with chronology; most describe events that could be taking place right now, but most of those events had taken on their color before any of us was born. There is a conviction here that every way of life practiced in America from the time of the Revolution on down still matters — not as nostalgia, but as the necessity of someone’s daily life — and the music, though it never bends to any era, never tries for any quaint support of a theme, seems as if it would sound as right to a gang of beaver trappers as it does to us. There is no feeling of being dragged back into the past for a history lesson; if anything, the past catches up with us.

So in a twist of fate, nearly the same day as the death of Robbie Robertson on August 9 — a man who made such a profound impact on music that Eric Clapton confessed at The Band’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony that he wanted to drop out of Cream to join them — Virginia former millworker and singer/songwriter Oliver Anthony went viral with his song “Rich Men North of Richmond.” Robertson was a master of recognizing the beauty in the American story in all its nuanced layers while lamenting the cruel nature of a knee-jerk counterculture that lost its way because it never cared to know from where it began.

The same could be said for those who carry on the tradition of Americana now. It could be Anthony or anyone eschewing the rules laid down by the powerful who never has to live by them, living outside artificial parameters set by corporate interests, media snake-oil salesmen, or politicians with wide smiles and thieves’ hands. They scorn the traditions and way of life of their brothers and sisters they never bother to understand. They sing for themselves while the Americana bard sings for the silenced. The busybody online mobs cry rainbow tears as working-class families desperately inhale anything with an air of authenticity like every breath could be their last. The 19th-century traditional Christian hymn “I Am a Pilgrim” draws a straight line through folk, gospel, and bluegrass, released on Sweetheart of the Rodeo, recorded by Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, embodied by Dylan, and lived by The Band.

I am a pilgrim and a stranger

Traveling through this wearisome land

I've got a home in that yonder city, good Lord

And it's not, not made by hand

This is a new era. Americana pushes back against the extremes threatening to tear us apart; a middle ground where the culture comes together in a collective sense of basic understanding and responsibility to history, the present, and the future. Americana is a collection of threads pulled from the best of times and the worst that doesn’t make the most beautiful or pristine tapestry but one with a rough appeal that will withstand the elements of the worst storms and the most intense heat. The modest lines allow us to build our own stories. We pull from emotion and experience, adding complexity and authenticity that only the listener and creator can make for and with each other, not dictated to tin ears or sunshine patriots, but for the restless pilgrim who leaves a bit of himself behind so he can return home.

Outstanding analysis, penetrating insight, and gracefully written as always, Jenna! As you know, I'm more than a little pessimistic about the country's trajectory. You are the one writer, indeed the one mind and spirit that encourages me to pause and reassess my own rather brooding outlook. For that, I owe you my sincere gratitude and undying admiration.

Thanks for posting this... I remember those bands and the care they took in their craft. Today's music is 98% crap except people like Jason Aldean, Oliver Anthony, and others like them.