Common Men, Common Heroes

The immeasurable cost of one life is measured in the lives of others.

The epilogue is the human heart beating life into what would otherwise be a mere (and certainly memorable) story. That is true for the popular WWII-era television series HBO’s Band of Brothers in 2001, its 2010 Pacific-theater companion The Pacific, and Apple Studio’s recently released Masters of the Air. At the conclusion of all three mini-series — which are based on actual historical events — the real men who are portrayed onscreen are revealed, and their post-war lives are summarized. No matter how technically precise, how stomach-churning the action, or how raw the actors’ performances were, there is no comparison to how men who summoned such incredible courage and faced insurmountable obstacles retired into the everydayness of American life. Nothing can connect one soul to another at the barest, most simple level — staring back at us from the television screen in black and white photographs just like the ones we have of our grandparents stuffed in a drawer somewhere; these small, delicate, colorless windows into a world that doesn’t exist today even as their legacy exists everywhere.

The truth is that these men were heroes, regardless of whether their stories became Hollywood pictures, glossy magazine serials, or newsreel features. The stories we don’t hear speak to what was lost — and gained — in cruel twists of fate, fortune, life and death.

Perhaps the enormous loss of life for a just and righteous cause made one understand the value of each life in sustaining that cause; the intimate horror of battle gave purpose to each breath of freedom.

Writer Ernie Pyle was killed on the Pacific Island of Ie Shima (now known as Iejima), a small island northwest of Okinawa, on April 18, 1945 weeks before WWII ended; he was 44 years old. His dispatches from the campaigns in Northern Africa, Italy, and the Normandy Invasion embedded with the U.S. Army as a war correspondent won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1944. His column was featured in hundreds of daily and weekly newspapers at the time of his death.

To us today, the storyteller is the hero of the story, so it is a peculiar concept to consider this man who hated war, with a frail and unassuming demeaner, and who cared for each man’s story — as unremarkable as it may seem — as if it was ever the only story worth telling. It endeared him to Americans back home and to millions of military men scattered across the globe in the only cause worth fighting and dying for. It was about one man just as much as it was about millions of men. One million battles for one single victory.

TIME magazine paid tribute to Pyle in its July 17, 1944 cover story:

“Homesick, Violent, Common Men.” What happened to Ernie Pyle was that the war suddenly made the kind of unimportant small people and small things he was accustomed to write about enormously important. Many a correspondent before him had written of the human side of war, but their stories were usually about the heroes and the exciting moments which briefly punctuate war’s infinite boredom. Ernie Pyle did something different.

More than anyone else, he has humanized the most complex and mechanized war in history. As John Steinbeck has explained it:

“There are really two wars and they haven’t much to do with each other. There is the war of maps and logistics, of campaigns, of ballistics, armies, divisions and regiments—and that is General Marshall’s war.

“Then there is the war of homesick, weary, funny, violent, common men who wash their socks in their helmets, complain about the food, whistle at Arab girls, or any girls for that matter, and lug themselves through as dirty a business as the world has ever seen and do it with humor and dignity and courage—and that is Ernie Pyle’s war. He knows it as well as anyone and writes about it better than anyone.”

These wars were never as simple as “our” fight. Of a sweeping, epic battle of Good versus Evil or defending a notion of civilization or the survival of the West. Of course, it included those things, but in the pit of our loins, somewhere in us that is easy to ignore except in the dark cover and silence of the night, there was a battle in the heart of every man facing that looming beachhead that mountain ridge, or that jungle abyss. And we see now, hopefully, eternally, that even as the ocean and earth swallow the horrors of that day for those men — like so many before and yet to come — it was about how those men slain the devil lurking on their shoulders in those fateful hours of battle. They were forced to face it so that we never would. And that battle died with them.

The 1946 picture, “It’s a Wonderful Life” has a resounding, reflective theme, often overlooked because of its holiday tradition etched in our collective nostalgia. That we cannot measure the worth of a man by his accomplishments, deeds, or fame. Look to the lives of those around him. Capra, whose family emigrated to America in 1903 when he was five, served in WWI. Capra went back to the U.S. Army commissioned as a Major at the age of 44 after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. He directed a “Why We Fight” documentary series under orders from Gen. George C. Marshall. In his 1971 autobiography, Capra recalls Marshall’s mission,

Now, Capra, I want to nail down with you a plan to make a series of documented, factual-information films—the first in our history—that will explain to our boys in the Army why we are fighting, and the principles for which we are fighting ... You have an opportunity to contribute enormously to your country and the cause of freedom. Are you aware of that, sir?

How did Capra create such beautiful, lasting portraits of Americana that stirred men to fight one day and bring tears to their eyes on another? Perhaps it was his connection to servicemen during two great wars, or his fierce patriotism, or an understanding of the Everyman whose worth is ultimately known only to God.

As we look at the men who laid bare their emotions and humanity on fields scattered around the globe in centuries past, their souls transcend time and place. Their eternal spirits are heard in every American flag beating in the wind of the stormiest seas or silently holding watch over mist-covered cemeteries. These are boys who would never become men but for the few hours of chaos and rifle fire exploding around them hundreds of miles from home. Those are the heroes who exist in the lives of the living.

Jimmy Stewart’s character George Bailey in “It’s a Wonderful Life” receives a gift. He is shown what one man’s life is worth. The angel, Clarence, explains, “Strange, isn't it? Each man's life touches so many other lives. When he isn't around he leaves an awful hole, doesn't he?”

So, the question to ask is, what do we owe them? This is a preposterous question to which the only answer is everything.

How, then, do we chip away, however futile, at this insuperable debt? Never accept the common as the insignificant. Never forget that the price of the everydayness of our lives was the life of another. Never settle for the choice in front of you — the cost is much too great. Demand more of our leaders, demand more of our neighbors, demand more of our kids, and demand more of ourselves. Because each man’s life touches so many others.

Less than five years after the end of World War II, American troops were landing on the Korean peninsula, and the nation was at war once again. On June 25, 1950, more than 135,000 soldiers of the People’s Army from Russian-occupied North Korea invaded the Republic of Korea in the south, crossing the 38th Parallel. By July 27, 1953, the Korean War would come to an end. For a war that is too often referred to as “forgotten,” the price for it ending in armistice was enormous: According to the U.S. Department of Defense, 36,574 Americans died in the Korean War — it was the United States' second deadliest conflict of the Cold War, as well as its fifth deadliest ever, after Vietnam, World War I, World War II, and the Civil War.

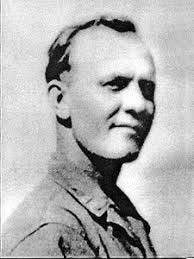

Among those 36,574 Americans killed was Army Captain Edward C. Krzyzowski of Company B, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, born in Chicago in 1914. A man like any other man until he wasn’t. Until he faced the devil that rose from the earth scorched by war and sacrificed his life for countless others. A life ended, and a life immortalized — the tragic gift of the fallen to those who live. Capt. Krzyzowski posthumously received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions from August 31 to September 3, 1951 during the Battle of Bloody Ridge. I came to know his story from a note I received from a reader last week. His father, a hero in his own right, certainly to his son and grandchildren, was saved through the selfless actions of Capt. Krzyzowski. One man’s life touches countless others. Craig writes,

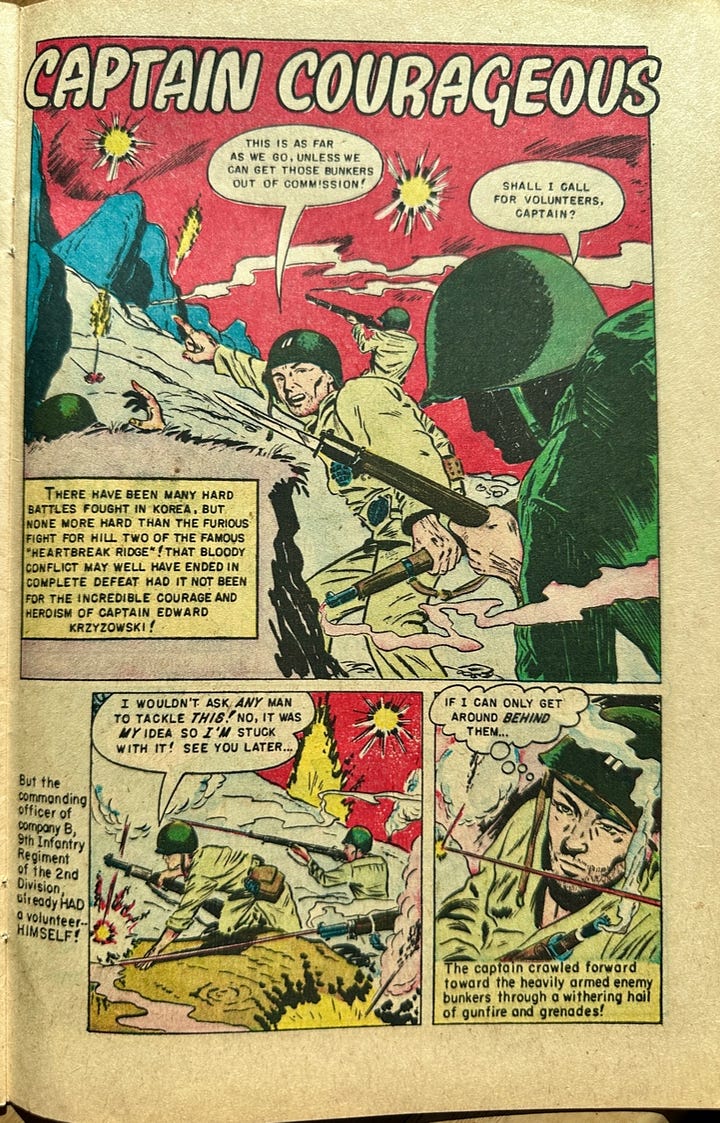

I published that piece last November, and shortly thereafter I connected with the youngest child of Capt. Krzyzowski. He never knew his father. He was a baby when his dad was KIA. We have communicated via email. He sent me a few images of his dad and some newspaper clips. It was he who told me about the Heroes comic book. I bought a pristine copy for my son to have. He loves military history; earned an B.A. in history at New Mexico State. Dad’s invested combat pension money paid the way.

It is all very humbling. I am so grateful to be an American and very glad my two daughters were born in the USA.

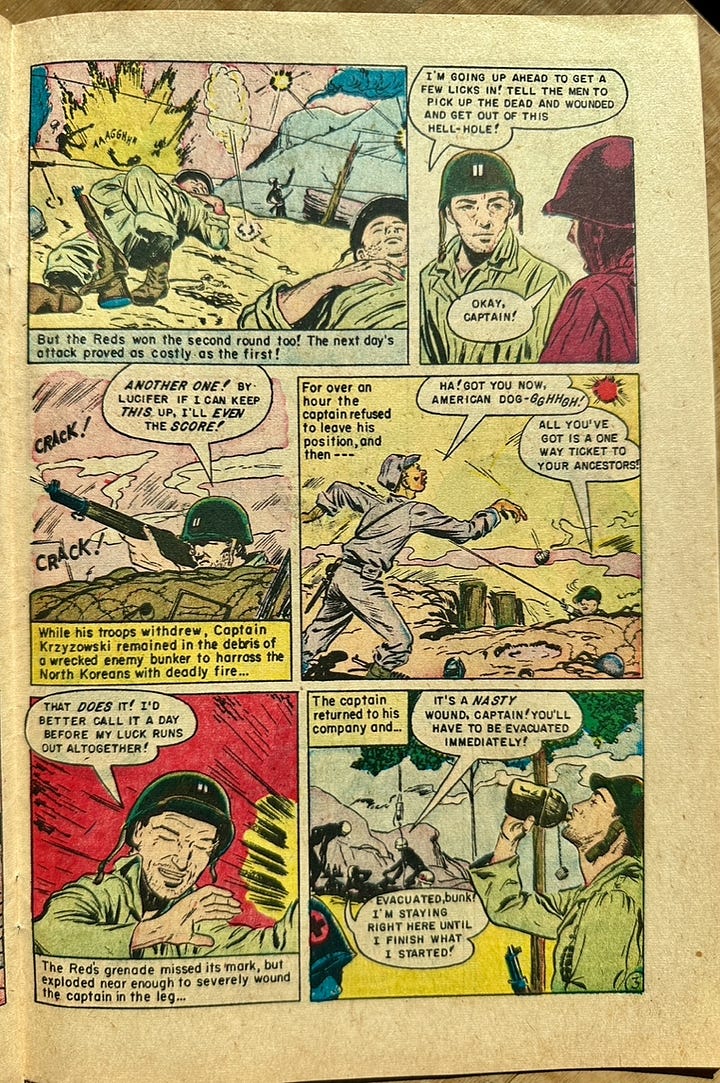

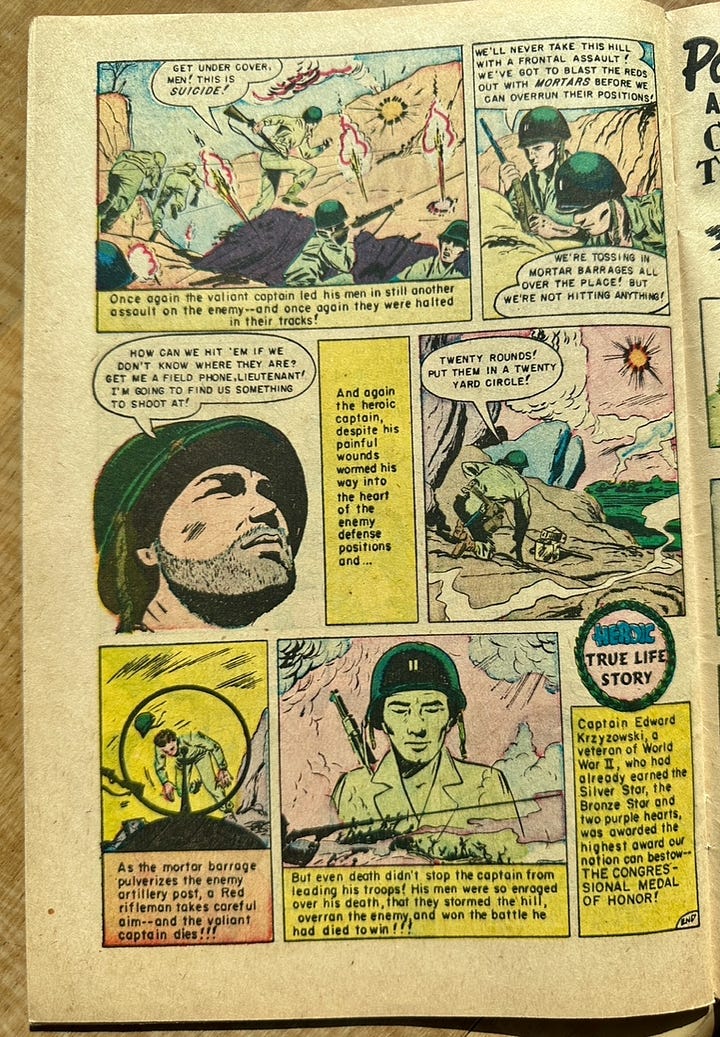

Craig wrote a graceful tribute to his father, Ernest, here. By all accounts, Ernie was a brave soldier, patriot, and loving father and grandfather. A grateful nation honors his service to the country, and I am thankful that such men were, and are, among this nation’s finest. I included the New Heroic Comics (Issue #77) portraying Capt. Krzyzowski — Captain Courageous — and his Medal of Honor citation.

Capt. Krzyzowski, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and indomitable courage above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy as commanding officer of Company B. Spearheading an assault against strongly defended Hill 700, his company came under vicious crossfire and grenade attack from enemy bunkers. Creeping up the fire-swept hill, he personally eliminated one bunker with his grenades and wiped out a second with carbine fire. Forced to retire to more tenable positions for the night, the company, led by Capt. Krzyzowski, resumed the attack the following day, gaining several hundred yards and inflicting numerous casualties. Overwhelmed by the numerically superior hostile force, he ordered his men to evacuate the wounded and move back. Providing protective fire for their safe withdrawal, he was wounded again by grenade fragments, but refused evacuation and continued to direct the defense. On 3 September, he led his valiant unit in another assault which overran several hostile positions, but again the company was pinned down by murderous fire. Courageously advancing alone to an open knoll to plot mortar concentrations against the hill, he was killed instantly by an enemy sniper's fire. Capt. Krzyzowski's consummate fortitude, heroic leadership, and gallant self-sacrifice, so clearly demonstrated throughout three days of bitter combat, reflect the highest credit and lasting glory on himself, the infantry, and the U.S. Army.

Wonderful coverage of our greatest generation. Thank you!

Thanks Jenna, for the reminder of a debt it's too easy to forget.