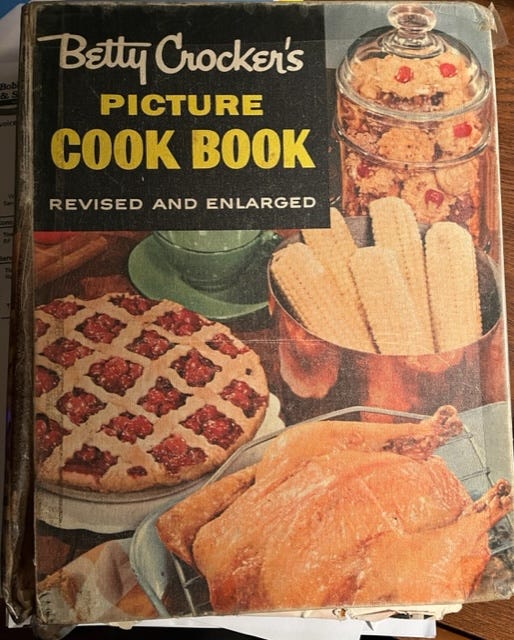

Before Thanksgiving, I was sent my grandmother’s second edition (1956) Betty Crocker’s Picture Cookbook (Revised and Enlarged!) from my aunt in Maine. A mainstay in Minnesota since the 1920s, Betty Crocker’s legacy is richly intertwined with the state and with the ever-evolving story of homemakers and home cooks. The Minnesota Historical Society has a page dedicated to Betty and her “origin story” is detailed on the Betty Crocker website:

We got our start in 1921 — and thank you, we do look good for our age. Who could have guessed that a simple contest by The Washburn-Crosby Company would give birth to an icon? The contest called on home cooks to solve a jigsaw puzzle for the chance to win a pincushion in the shape of a bag of Gold Medal Flour (cute). Washburn, a flour-milling company and predecessor of General Mills, Inc., was surprised to find themselves suddenly inundated with questions from home cooks who used the competition as an opportunity to ask for expert baking advice.

Betty went on to radio, informing housewives on the proper cooking techniques and latest recipes through the local station WCCO and her red spoon was the unofficial seal of approval emblazoned on mixes and convenient goods in Red Owl grocery stores far and wide. Now I even work in an office building located near Betty Crocker Drive and General Mills Boulevard.

But what struck me about laying eyes on the same book that served my grandmother Joan — who married a farm boy that went on to fight in Okinawa during World War II, herself going to Seattle to help the war effort with her best friend Esther as “Rosie the Riveters” in the shipyards, who raised a family in Minneapolis and was a ticket-taker at the old Met Stadium, sewed all the clothes, made all the meals, had no time to suffer fools or gossips, and was a social hostess to many games of 500 — was just how worn and fragile it had become.

Every chapter tab, from “Special Helps” (Save time…Insure sanitation: Rinse dishes with boiling water, leave on rack to dry. Wipe glasses, silver. Some prefer to wash dishes only once a day. Saves soap, time. Rinse and stack, then cover.) to “Vegetables” (Asparagus in Ambush was intriguing: “Roll cooked stalks of asparagus in thin slices of boiled ham or dried beef. Broil. Serve with Cheese Sauce or White Sauce.”) was frayed to the nub. Scotch tape, layered and yellowed, bound the edges of the front and back cover, which still didn’t keep it from being broken at the spine. Pages throughout were splotched and blotted with various remnants of whatever sauce had been boiling on the stove (hot tartare, perhaps?), layered into a baking dish (Scalloped Chicken Supreme, which required a topping of Wheaties), or delicately poured into a pie (Butterscotch Cream — new to me that I decided to make for my family’s Thanksgiving feast as a kind of tribute).

I imagined my grandmother paging through it, planning for the next meal or a larger family gathering. Maybe she and my grandfather would have company over on a Saturday night and something special was in order. “Main Dishes” came with this warning, “Poorly made main dishes have come to have a bad reputation, especially among men, as a substitute for meat. But a well seasoned, well cooked main dish can be as interesting and satisfying as a good steak.” And Betty Crocker knew her audience. As the head of a working-class family, my grandmother read about buying meat with a frugal eye, how to stretch leftovers, buy canned goods, and cook everything properly (hence not to waste) from squirrel to squab. Readers are enlightened by the little insights and encouragements found in nearly every recipe. Under Spareribs and Sauerkraut on page 317: “Choice of one of Hollywood’s most exotic movie stars of all time.” Exotic! Earmark that for Friday night supper.

Now, by the time I was old enough to join her in the kitchen I never once saw her open a recipe book or dive into her box stuffed with index cards on which were written in that cursive — the type that every adult of a certain generation seemed to have carbon copy — a recipe from one of her girlfriends or a sister-in-law. And when I look back on it now, for as wonderful and versatile a cook as she was, she hardly had anything in her kitchen. There were the nesting glass mixing bowls, covered hotdish ware, a hand mixer, and various wooden spoons and rubber spatulas — which probably got as much use paddling the fannies of misbehaving kids as mixing ingredients.

And now if you walk through a Target store or turn on the television, there’s an endless stream of gadgets and multi-cookers that promise to dehydrate your meats, fry your chicken, steam the vegetables, fluff the rice, walk the dog, and help the kids with their homework. But with all the modern conveniences, the time savers, the quick cooks, and the self-cleaners, it seems like we live in a world with a perpetual shortage of time and an overabundance of frayed nerves.

I’ve spent a lot of nights lately lying awake, staring into the stillness of a house asleep, just the streetlights and static hum of various gadgets and plugs and screens mocking me that there really isn’t anything like silence in a connected world — in which I pretend I control all those things rather than the other way around.

But my restless mind hums along with the electronic mod cons to a time I don’t know firsthand but for which I feel a particular nostalgia. And my grandmother’s cookbook rekindles such a halcyon spark especially when I’m now a wife and mother with a household full of duties and responsibilities that always seemed to be so far into the future but now have me longing for days long past. When I have the unbelievable good fortune to be born into the modern West with its medicine, wealth, and opportunity — yet the trappings of society can leave a void that no gadget or email will fill, nor Google search will answer. What makes a modern working mother? I have all the technology to save hundreds of hours on cleaning and cooking, yet I never seem to have enough time to fold the laundry or sort out the junk drawer or unpack the last boxes from when we moved eight years ago.

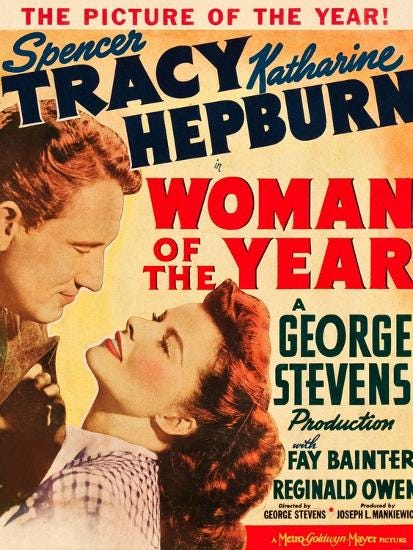

I look at this cookbook and see women balancing their family roles, keeping house, shopping, mending clothes that they made, cooking wholesome meals, and spending real time with their families, uninterrupted by screens except for the one television in the den that didn’t have a remote, and wasn’t filled with an endless stream of blaring faces and brain garbage. I think of the famous scene in the 1942 Katharine Hepburn-Spencer Tracy film Woman of the Year, in which the careerist political reporter Tess Harding (played by Hepburn fresh off the classic The Philadelphia Story) attempts to make breakfast for her husband, despite her obvious ignorance of how anything works in a kitchen. It’s a great scene and feminists have criticized it as an appeasement to domesticity (*oppressive patriarchy).

Three or four generations removed from the feminist revolution and society has undoubtedly benefitted from the advances and opportunities for women. But there still seems to be a portion that keeps fighting some invisible fight against inequality without realizing what the cost is in such a tradeoff. Because nothing happens without consequences. We have more women who feel unfulfilled by an identity that relies exclusively on their careers. We have more women delaying marriage and children. We have more women who are affected by depression and anxiety and who feel confused about their role in society. We have more driftless men and anxious children. There is a breakdown of security, happiness, meaning, and fulfillment — all things that start in the home and rely on a strong family foundation.

We are told that women can have it all without telling us what it all is. And I have a feeling I could find it in the pages of an old, worn 1956 cookbook than my Google Assistant.

Your art for depicting and respecting nostalgia is a gift. You are quite a bit younger than those of us who did flour and Crisco up a new Betty Crocker Cookbook.

I miss those days and would give anything for this generation to experience that level of simplicity.

Back in the old West, women had a low incidence of depression because they sat in a circle and talked while making quilts. Just talked and stitched from leftover fabric, creating beautiful, functional art. Now, it's an Amazon order.

Great piece, Jenna! Like I have said before, you make this old girl think, and I will never look at that Betty Crocker Cookbook the same again. ❤️

“Now, by the time I was old enough to join her in the kitchen I never once saw her open a recipe book or dive into her box stuffed with index cards on which were written in that cursive — the type that every adult of a certain generation seemed to have carbon copy — a recipe from one of her girlfriends or a sister-in-law.”

Jenna, to plagiarize a line from a well known movie — you had me at “her box stuffed with index cards.” Our hand-me-down recipes are in a little white metal index card box decorated with a blue & yellow Pennsylvania Dutch folk art border. Among the cursive written recipes is one from my mother-in-law’s blueberry steam pudding baked in a previously used Maxwell House coffee can. There’s also another recipe from my mother for her Jewish apple cake. If I’m lucky, my wife will make one for my birthday. Sometimes life gets in the way & I get a supermarket-bought Jewish apple cake. I usually say, in a sorta gracious, understanding way, it’s ok, “I remember what they look like, I have pictures.”