For, after all, you do grow up, you do outgrow your ideals, which turn to dust and ashes, which are shattered into fragments; and if you have no other life, you just have to build one up out of these fragments. And all the time your soul is craving and longing for something else. And in vain does the dreamer rummage about in his old dreams, raking them over as though they were a heap of cinders, looking in these cinders for some spark, however tiny, to fan it into a flame so as to warm his chilled blood by it and revive in it all that he held so dear before, all that touched his heart, that made his blood course through his veins, that drew tears from his eyes, and that so splendidly deceived him!

― Fyodor Dostoevsky, White Nights and Other Stories

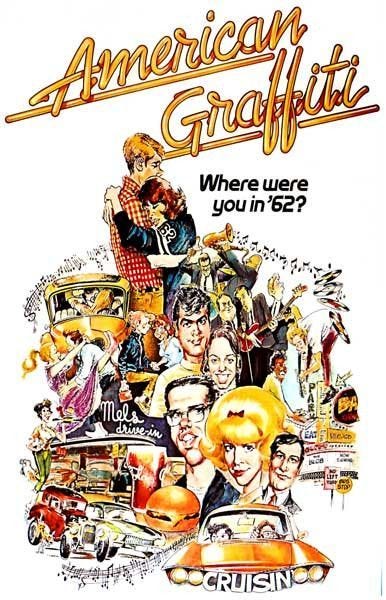

Once upon a time, America held the dreams and ambitions of the world in its roaring chrome and neon-lit soda jerks, blasted through the atmosphere with flames on its heels and grease in its hair, shot through the night on roll-stitched vinyl bench seats, Lucky Strikes, gauzy skirts, and letterman’s sweaters. It was The American Century — the dawn of the Space Age colliding with sock hop sweethearts, a crooning Sinatra dueled radio dials with Bill Haley and his Comets, and suburban sprawl jutted against the Blackboard Jungle. America was coming of age. By the early 1960s, the country enjoyed a confidence that launched a thousand dreams before it turned a corner mid-decade and found itself lost in a fun-house mirror of unrest, unsure of itself, disoriented in the midst of rapid change, and leaving people asking, “Where we you in ’62?”

Fifty years ago this August, a twenty-eight-year-old filmmaker named George Lucas (in only his second film) asked moviegoers exactly that question when he made American Graffiti. The contrast between 1973 America and the one only a dozen years earlier was as clear and pronounced as the big screen of a drive-in: peering into a past of heady, halcyon nostalgia and warm memories of innocence and youth and vigor — all the trappings of cynical adults blinded by rose-colored glasses. But this story was told through the lens of Lucas’s camera and his mind’s eye. And that is what makes it stand out as an enduring and endearing Kodachrome moment of Americana. Looking at the 21st century, one can’t help but ask, “Are we still the America of ’62?”

American Graffiti is the coming-of-age story of four teens facing the crossroad of their futures, all in harmony with the music that defined the times. Curt, Steve, Terry “Toad,” and John (played by relative unknowns Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Charles Martin Smith, and Paul Le Mat, respectively) each had storylines that played out in front of a backdrop of small-town America with hardly an adult in sight but plenty of white walls, chrome, and roaring engines over Rock & Roll records and rows of storefronts and streetlamps. The film follows the four friends as they embark on a one-night journey cruising and carousing through their town in search of their future and facing the reality that time will either pass them by or they open their sails and ride out the wind of change wherever it takes them.

American Graffiti isn’t sing-songy bubble gum snapping pony-tailed nostalgia fluff, but rather a stylized documentary that plays out the real conflict between two worlds: the shelter of the familiar, comfortable, and stagnant, and the unease and uncertainty of leaving that all behind to face the responsibility, possibilities, and opportunities of adulthood. It is more than these four young men; it is the coming of age of the country itself, living out the last gasp of a golden age before a massive social upheaval begins in earnest.

Buddy Holly and the Crickets, The Flamingos, The Big Bopper, Fats Domino, Del Shannon, and Chuck Berry — a few of the artists that comprise the 41 songs on the soundtrack of a singular era that ended before anyone knew it was gone forever. The music creates the scenes rather than serving them, as Lucas and sound supervisor Walter Murch effortlessly incorporate tunes to seem pervasive in each scene: coming from car radios, gym speakers, served up with the drive-in burgers and chili fries, so ubiquitous and unobtrusively natural to the era that one can feel the dimes jingling in cuffed chino pockets and dungarees waiting to be dropped in the juke-box slot. That was the magic of Lucas’s tale. One isn’t just an observer, peeping on the lives of these teens during one warm, meandering night. The audience is transported there, helped in part by Lucas’s innovative technique of using a Techniscope anamorphic process to mimic the grainy feel of a documentary. And in some ways, it was.

American Graffiti offers a fleeting glimpse of The American Century. Mid-century America was the land of abundance and excess, of Greasers and Rock ‘n Roll, hot rods and muscle cars, sock hops and hootenannies, chili dogs and tiki bars. We arrived there through the growing pains of war, finally facing the responsibility we were destined to undertake.

“The American Century” was the title of a 1941 essay published in Life Magazine written by the magazine’s founder, Henry Luce. In it, Luce offers a prescription for the hesitancy Americans felt as the world headed for war writing, “Accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.” America, coming of age.

America had a responsibility to lead the world in this most crucial time, not because we are perfect or had the brute power to make other nations bend to our will or because of some tyrannical propensity. America should lead because we are leaders. A world with America at the helm is far better off than one without. It was under this blanket of self-assuredness, self-respect, and collective patriotism that Americans could live mostly unburdened by the shackles of war and economic volatility and within an accepted social order built on traditional values, respect, hard work, and opportunity.

But it wouldn’t last. Political scandals, war, and social upheaval changed the nation’s landscape with such sweeping ferocity that a film made about a time just a decade earlier would be a smash hit because it harkened to an era still living and breathing in the soul of a huge portion of the population. It was simpler, perhaps because the teenage years are simpler without the grownup mind-weariness of jobs, family obligations, and more serious worries always on the horizon. Teenagers were free to be…free from that and pursue their dreams. In the America of American Graffiti, there are no cell phones, TikTok, dating apps, or car power windows. But life rolled on through the streets of small towns and big cities —breezy summer nights crowded in cars under starry skies with cigarette lighters in the dash.

It was here, nestled in the comfort of America coming of age, growing into its responsibility, and excelling at it, that Lucas sorted through his collection of 45s, pairing songs to scenes in when he wrote the initial American Graffiti screenplay, making the project both a personal retrospective of his experience growing up cruising the streets of Modesto, California, and universal in its appeal to a generation that never thought the days of innocence and optimism — represented in the raucous, carefree hip-shaking, crew-cut Rock & Roll, longing gazes of doo-wop, and rim-shot magnetism of backbeat soul — would fade like an old photograph.

Contrast that with today. We’ve lost our footing and our confidence. Politics is inescapable and becoming inextricable from everyday life — everything from what brands we wear and cars we drive to what music we listen to and what schools we attend come with political identity stamps herding us all into tribal camps with boilerplate opinions. These things formed little communities apart from politics but now define our politics. Kids and teenagers no longer have the option to live a mostly carefree life a child should expect because they’re too often used as political pawns: for gun control and climate change to trans-activism and abortion. They are robbed of their own coming-of-age story because they’re foisted upon with the political projections of selfish adults who care more about grasping the last bit of power for their own legacy than preparing the next generations for what they leave behind. They don’t know where to go because they don’t properly understand where they came from.

The prolific writer Tom Wolfe wrote in his 1987 essay “The Great Relearning” in The American Spectator:

People of the next century, snug in their Neo-Georgian apartment complexes, will gaze back with a ghastly awe upon our time. They will regard the twentieth as the century in which wars became so enormous they were known as World Wars, the century in which technology leapt forward so rapidly man developed the capacity to destroy the planet itself—but also the capacity to escape to the stars on space ships if it blew. But above all they will look back upon the twentieth as the century in which their forebears had the amazing confidence, the Promethean hubris, to defy the gods and try to push man's power and freedom to limitless, god-like extremes. They will look back in awe . . . without the slightest temptation to emulate the daring of those who swept aside all rules and tried to start from zero. Instead, they will sink ever deeper into their NeoLouis bergeres, content to live in what will be known as the Somnolent Century or the Twentieth Century's Hangover.

Are we still the America of 1962? I don’t know. But at least we have a record of what it was like in that America — a reminder that the sophisticated and complex, faster world isn’t necessarily a better or happier world. That some things look better under a neon sign, and sometimes you must leave a place to find your place. Lucas had it exactly right on film, we have it forever.

Thanks for this "Fifty Years of American Graffiti" post! I was in High School in 1962 and remember the time fondly. Sadly, it was in 1962 that prayer was taken out of our public schools. The United States Supreme Court ruled that school-sponsored prayer in public schools violated the First Amendment and was unconstitutional. It has been all downhill since then. 1962 was the last good year, but then 1963 marked the JFK assassination, followed months later by LBJ's decision to send combat units to Vietnam... leading to the chaotic mess we are in today. I just restacked this post!

A poignant reflection. A treasure from the lost and found.